The Folk from the Wind Wound Isle > Chapter 11 : Robert Robertson

page 49

Born 1853 - Died 1941

Born at Hellister, Shetland on 8 May 1853, Robert was the fifth son and eighth surviving child of Margaret Henderson and Arthur Robertson. There are stories about Robert’s early life in the section on ‘Life in Shetland’. As with those stories, much of the following information comes via his daughter Lottie.

Robert Robertson’s Box >

The box in which he brought all his possessions to Australia in 1866.

Robert was thirteen years of age when he arrived in Australia. All his belongings were contained in a small box made of Scottish pine. This box has neatly dovetailed corners and measures 45 x 27 x 23 cm. Over the years the box has been used as a toolbox and a saw bench, roughly repaired and painted. It is now in my custody and I have stripped the paint off and restored the box to the natural wood.

Soon after reaching Geelong, Robert broke his arm and was in the Geelong hospital. While in the hospital he was recruited to assist the medical staff with a man who had cut his throat and this experience gave him a lifelong dislike of hospitals. Robert moved with the family to Lara, then to the western district where Lottie believed the family had a property at Mt Elephant or Mt Violet.

Robert and Mary Jane CAIRNS (1859?-1942) were married by license, according to the rites of the Presbyterian Church at Derrinallum on 3 April 1875. The signature of the minister is difficult to decipher but his surname appears to be Ellerman. The marriage certificate gives Mary's age as fifteen, with consent for her marriage being signed by her mother. Robert is recorded as being twenty-two, a stone waller presently of Derrinallum but his usual place of residence as Port Campbell. The marriage was witnessed by Margaret Cairns Snr (her eldest daughter was also called Margaret) and Michael McCue. Mary Jane, who was known in the family as Molly as well as Mary, would have been about five months pregnant at the time of her marriage. She was the seventh child and third daughter of Margaret Rutherford and George Cairns. (See Chapter 9 on Arthur Jnr.). Molly’s date of birth is uncertain and several of the Cairns children seem to have been unregistered. I understand the day of birth is July 5 and to fit in with other children in her family it would have had to be in either 1859 or 1860.

Taking his wife to Port Campbell, Robert built a slab hut on the land he had selected. Lottie Dickins tells us, “Robert took contracts for building stone walls (farm fences) and stone sheds. Uncle Jimmie and his two sisters’ husbands [Chiselett and McCue] worked for him at different times. Molly and Auntie Frances [James’ wife] used to camp on the job with the men and do the cooking. Sometimes Molly was left by herself for days at a time - it was then the koalas would cry like babies and frighten her. Later when she had children she would be by herself with the children for long periods.” 1 Returning home one day, Robert found the house reduced to ashes

page 50

and the family's possessions destroyed. ‘There will be no need for me to take off my coat to start again‘ he is reported to have said, ‘because l have no coat to take off.' 2

The turning point in Robert’s life was the ‘Great Christian Revival‘ that swept through Victoria in the 1870s. Robert, along with other members of the family, heard the ‘call’, and decided to dedicate his life to

Piecing together the events of the revival and Robert's life as an evangelist is not easy. There seem to be a number of contradictions in reports from various sources. This includes Robert’s own version of events, published in 1937 - The Port Campbell Revival - from which I have already quoted extensively. Robert tells us he wanted to be baptised in Melbourne and the detailed description he gives of his meeting and subsequent contact with the Rev Samuel Chapman of the Collins St Baptist Church, suggests this man was an important influence on the person Robert was to become. Chapman came to Melboume from Scotland in October 1877 and he preached at Port Campbell in 1879, 3 so Robert's visit to him must have occurred some time between these two dates.

The minister's study was " at the back of the church. Making my way to the study door, l knocked and a clear distinct voice rang out, “Come in!" I was taken with the voice. I thought I detected a manly, cheerful ring in it. l opened the door and stepped into a cosy room, with a big coal fire burning in the grate.

“Sit down!” said he pointing to a chair on the right of the fire. He set himself down on a chair on the opposite side of the fire. Then we two men sat for a brief moment looking at each other and reckoning each other up. Mr Chapman was well groomed and well attired. He looked to me just the cultured city clergyman in a comfortable study as he looked at me, dressed as l was in a suit of “reach me downs," with hair and boots to match, straight from my forest home.

We looked to be very different men outwardly, but under all the externals we were alike in one trait, viz., in each of us there burned a desire to lead men to Christ. 4

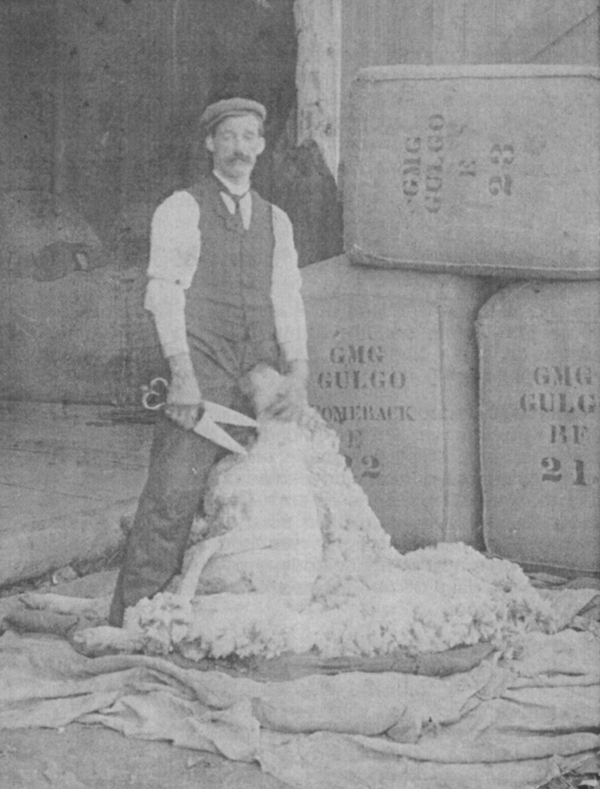

From his obituary we learn that Robert had little formal education and started his working life as a tanner. He worked as a shearer and later as a shearing contractor. He continued working at these occupations while devoting ‘all his spare time in seeking the salvation of others.’ His brother Arthur supplied him “with teams and vehicles to do work in the shearing sheds". 5

page 51

Whether Robert means he was shearing sheep or undertaking evangelical work is not clear, probably both.

In preparation for the evangelical work he was to undertake, Robert studied English, Greek, Latin and Science. He was indeed a self-educated man and continued to study throughout his life, and encouraged the pursuit of learning in his children. He was never ordained, but was always known as either Pastor or the Rev Robertson.

Robert Robertson - the shearer >

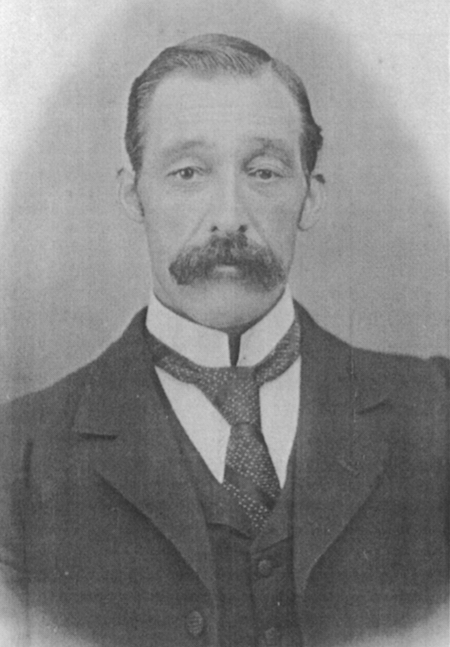

We should not underestimate the role of Molly Cairns in encouraging Robert's evangelical work and shouldering the burden of raising her children very much on her own. Robert himself pays tribute to her in his writing and tributes to Robert rarely fail to mention the contribution to his work that his wife made. This is relatively unusual for the time when the role of a wife was rather taken for granted and left unspoken.

Mary Jane Cairns >

Robert and Molly had nine children, Rab, Nan, Josh, Arthur, Margaret, Glady, George, Lottie and Stuart born between 1875 and 1898. “When an epidemic of diphtheria visited the Port, Mrs Robertson had five of the children down with it at one time. By careful nursing she saved them all. There was as far as possible one free night in the week at her home, when the young people could invite their friends to the house. The evening would be spent in song and useful conversation; perhaps a reading or debate.” 6 Describing his mother to his daughter Pixie, Arthur Robertson said of Molly, ‘She might be doing some household task such as the washing and someone would come to the door and need advise or someone to pray for them and she would dry her hands off and leave whatever she was doing to attend to them." 7

Robert Robertson - the evangelist >

Insistent that his children should be educated, Robert moved his family away from Port Campbell because the educational facilities there were inadequate. This, according to Gordon Croft, was in 1887. 8 Jack McCue told his daughter Marjorie that Robert gave away ‘his block of land at a revival meeting, much to his Aunt Mary's distress’.

The family moved to Chilwell in Geelong and then to Belmont where they lived for eighteen years. Robert and his brother James joined the Evangelical Society as home missionaries. From that time on, Robert was often away from home, travelling throughout Australia and New Zealand, preaching and holding revival meeting. Vickery, a wealthy Victorian manufacturer, sponsored the tent missions he conducted throughout NSW. He would be away for anything up to nine months at a time, and the trip to NZ was even longer.

page 52

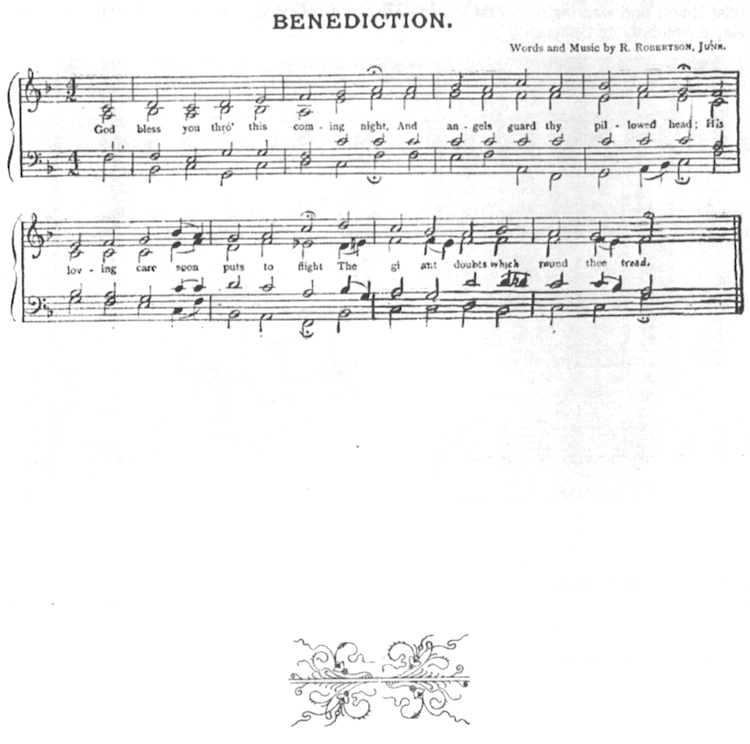

Sacred Solos

The cover includes a portrait of Robert and his son Arthur.

Robert was a gifted and moving speaker as a story related in his obituary demonstrates. A tent mission he was conducting “completely stranded a theatrical company in one town, making it impossible for the play to get an audience. In desperation the manager appealed to Mr Robertson to close down for one night in order to permit the company to get an audience big enough to finance the show and let it get out of town." 9

Stephen Sharp in a tribute to the Rev Robertson writes, "His descriptive faculty was unsurpassed, and he made the scenes he depicted live before his audience. His style, in the highest sense, was dramatic, and it sat perfectly on him, but not of the kind that lent him to imitation." 10 Robert wrote poetry and hymns, the latter in cooperation with his sons Rab and Arthur. A selection of Sacred Solos written/compiled by Robert Robertson was published, probably in the 1920s.

An example of Robert's writing style is contained in a 1939 Christmas card to Lottie. The Shetlander‘s affinity with the sea still seems to be there for Robert in his old age.

page 53

Seasonal greetings - may 1940 be your best of all years - you are on the crest of the wave of life - we are, as the western bound vessels - vanishing behind the cloud banks of life's years. With torn sails, rent cordage and only now a wreck and soon will be upon the shore, telling there life's perils o'er.

Despite the many tributes made to Mary Jane, we must wonder if she was always happy with Robert's behaviour and absences from home. Robert himself writes, at times she had to stand with uplifted eye and hand, crying: ‘The way is dark, my Father take my hand, and through the gloom lead safely home Thy child.'" 11 Lottie spoke of hard times when her father was absent for long periods and the family had to live on charity. Sometimes Lottie was sent to stay with relations, including her maternal grandmother, supposedly for her health, but perhaps also to relieve the financial load for Molly. Barwon House where the family lived after leaving Belmont was apparently a ‘grace and favour’ residence and part of the charity Lottie spoke of. “What an unhappy time that was," according to Lottie. Arthur, Glady and Lottie were all married at Barwon House, between 1914 and 1916.

Robert's affiliation with the Baptist church did not always run smoothly. At one point he argued with the authorities over some issue - Lottie suggests it was to do with his relentless opposition to drinking and smoking - and went to work for the Presbyterian Church. When the Presbyterians brought in a retiring age of seventy, Robert, who was well over that age at the time, went back to the Baptists. Jack McCue, visiting his Uncle Bob and Auntie Molly in the early 1930s, found they had no income, so he gave over his pulpit with its fee of £3 to Robert. Jack took their case to the Baptist Union and was instrumental in getting Robert called to the Baptist Church at Merlyston. Finally it was back to Belmont (Peary St) and permanent retirement.

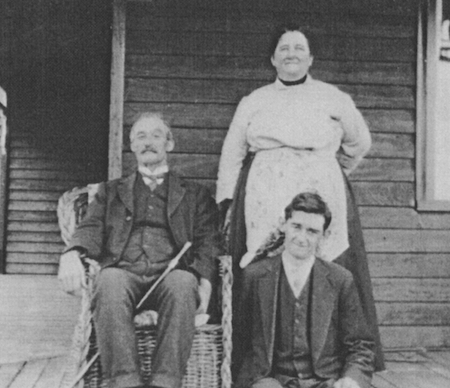

Robert and Molly Robertson with their youngest son Stuart at Dartmoor Manse in the 1920s >

Robert and Molly Robertson with their youngest son Stuart at Dartmoor Manse in the 1920s >

I was born towards the end of my grandparent’s life and only knew them as two old people we used visit at their home in Belmont, Geelong. I do not recall ever having a conversation with either of them, but I do remember the wonder of the music box that stood on a table in the front hallway. Marjorie Mathieson tells me that Grandpa used to keep a supply of the pennies in his pocket. These were needed to make the music play and he would hand the pennies out to visiting children. 12 On the other side of the fence, out the back of the house, there was a park with swings and slides and we children would be sent out there to play while the adults talked. In her old age Molly suffered from diabetes and dementia. In the garden at Peary St. red geraniums grew beside the path leading to the house and Molly was convinced they were little red men who came into the garden at night, ‘from over the bay’.

page 54

On the wall of the dining room at my mother's home in Melbourne there hung a fine photographic portrait of Robert in profile, taken in later life - white thinning hair and pince-nez glasses, head bent as he attends to the book he is holding. My mother Lottie Dickins adored her father. She told me that some months before his death she was aware of his presence standing at the end of her bed, even though he was far away in Geelong. She said that he told her he was ill and he would not recover.

Robert was the last surviving member of the family who had come to Australia from Shetland. He died at Geelong on 21 January 1941 and is buried at Port Campbell. Mary Jane died on 4 May 1942 and is also buried at Port Campbell.

Robert's mind was active till the end, as was his interest in life and the betterment of others. In 1937 Robert wrote, “The Federal Government should place two of our educated aborigines at Canberra as members of Parliament to represent the native interests. The Government should place there two cottages for the use of themselves and their families, paying the ordinary M.H.R. stipend to them. Under proper conditions, the race would increase. At present the conditions of our northern natives do us no honour. Were they in a mandated territory the League of Nations would have something to say about it. Our newspapers at times expose the seething filth forced upon our simple natives by sampan crews, whom our gunboats ought to chastise, and drive from our northern shores all such deeds and the doers of such deeds." 13

‘Benediction’ from Sacred Solos by R Robertson Jnr

1 Lottie Dickins, recorded by her daughters Marie Nemec and Margaret Worrall.

2 Paper cutting of Robert's obituary printed in the ‘Australian Baptist’, 11 February 1941

3 J.F. Wllkin, ‘Baptists in Victoria - our first century‘

4 R. Robertson, ‘The Port Campbell Revival’, p.33

5 Ibid, p.29

6 R. Robertson, ‘The Port Campbell Revival’. p 60

7 Interview with Pixie Robertson. March 2000

8 G. Croft. ‘The Chiselett Story". p.40

9 The Australian Baptist, 11.2.1941

10 Stephen Sharp, from a paper cutting kept by Lottie Dickins, dated 4.4.1941. The format suggests it is taken from The Australian Baptist.

11 R. Robertson, ‘The Port Campbell Revival’, p.59

12 Interview with M. Mathieson, March 2000

13 R. Robertson, ‘The Port Campbell Revival‘. p.63

Garry Gillard | New: 18 March, 2019 | Now: 5 September, 2022