The Folk from the Wind Wound Isle > Chapter 13 : The Children of Agnes Robertson and Michael Grace McCue

page 63

This section looks at the lives of Generation ‘C’, the grandchildren of Margaret Henderson and Arthur Robertson, all of whom were born in Australia. The chapters are arranged according to their parentage.

With the passing of the first two generations of Australian Robertsons, we find the lives and paths of their descendants beginning to diverge. Margaret and Arthur’s grandchildren married and came under the influence of other families. Many moved away from the Port Campbell area, and events, which were to affect all Australians, helped to shape a new generation.

On the whole, close family contacts were maintained in this next generation, with visits back and forth, long and short, between family members. Some lived in close proximity to their parents, siblings and cousins. Young people would be sent to live with older relations for health reasons, job opportunities or to help out when there were new babies or older folk to be cared for.

Other sections of the family maintained only tenuous contact with their relations. Two of James’ sons drifted off into the unknown and I have very little information about their lives. Another two of James’ sons, who settled in Western Australia lived in adjoining suburbs, but were seemingly unaware of the other’s presence near by. In the following generation, second cousins working in the Victorian police force were acquainted with each other but did not know they were related.

Today, the descendants of Margaret Henderson and Arthur Robertson are spread throughout Australia. Some have moved overseas. The only Australian state or territory where I have been unable to find any relations is Tasmania. There are still Robertson descendants living in and around Port Campbell. There are descendants who have maintained links with farming and those who choose to live in small country towns. However, like the majority of Australians, many Robertson descendants now live in cities.

Barbara Margaret Henderson McCUE (1871-1976) - MARRIED NAME CROUCH

Eldest child of Agnes Robertson and Michael McCue, born 7 January 1871 at Lake Tooliorook, (now Derrinallum) Victoria. Probably named after her mother’s dead sister. The name Henderson does not appear on Barbara’s birth certificate but she always believed it to be part of her name. The following details are pieced together from a variety of sources.

Barbara McCue attended the Loch Ard shipwreck at Port Campbell in June 1878. She and her sister Bean and brother Arthur ‘rode out through the backwater on their ponies, to view the wreck.’ There they saw the porcelain peacock that was washed up on the beach and is now in the Maritime Museum at Warrnambool.

From Barbara Rogers we learn, “My mother lived at Port Campbell and went to school there and when she was 16 years old lived with [her] Grandfather and Grandmother Robertson and cared for Grandma Robertson who was bedridden. She milked cows, took the milk to the creamery and did all the cooking and housework. She could not speak highly enough of Grandfather Robertson and her uncles, his sons”. 1 Marjorie Mathieson also tells us ‘Auntie Barb lived with Arthur Robertson [senior] to help with the work (milking cows, etc).’ 2

page 64

As a child, Barbara helped to steam and shape the arches for the windows in the Port Campbell Baptist Church and she was the first organist at the church after it was completed. Barbarasang with a fine soprano voice. Contained in Appendix 5 is a poem Barbara is thought to havewritten.

At some time during the 1890s Barbara went to live with, and keep house for her Uncle Willie and Aunt Jane at Beulah. Her mother Agnes suffered from hay fever and Lottie Dickins tells usthat Barbara, Bean and Aggie McCue all had weak chests and all eventually moved to the drierclimate of Northern Victoria. It was at Beulah that Barbara met her future husband. Barbara toldher youngest daughter they met at a cottage meeting where she was playing the organ. Edwinwalked in and Barbara said to herself, ‘this is the man I will marry’. Edwin described her as ablonde with blue Irish eyes. Seems it was love at first sight!

Barbara married Edwin CROUCH (1871-1950) at the Baptist Church, Beulah on 23 March 1898. The bride’s uncle, William Adie Robertson, conducted the service. Edwin was a cousinof Tot Collins, who would marry Barbara’s brother, John. Edwin was a farmer at Sea Lake andwas nicknamed Tim because he was always being helpful like Timothy in the Bible. The Crouchfamily - two brothers with their wives - came to Australia from Kent, travelling on the ‘Appolene’,which was the first ship to berth in the Port of Adelaide, on 12 October 1840.

Between 1899 and 1913, Barbara had nine children including two sets of twins. Stephen, who was a twin with Willie, died soon after birth and is buried beside Edwin Crouch’s sister, Ida Crouch, at Berriwillock, Victoria. Clifford (1910) died of Bright's disease in his third year and Clive who was Barbara Jnr’s twin, was killed in a riding accident at the age of seven. The surviving children were Arthur (1899), Ellie (1901), Willie (1903), Eddie (1905), Norman (1907) and Barbara (1913).

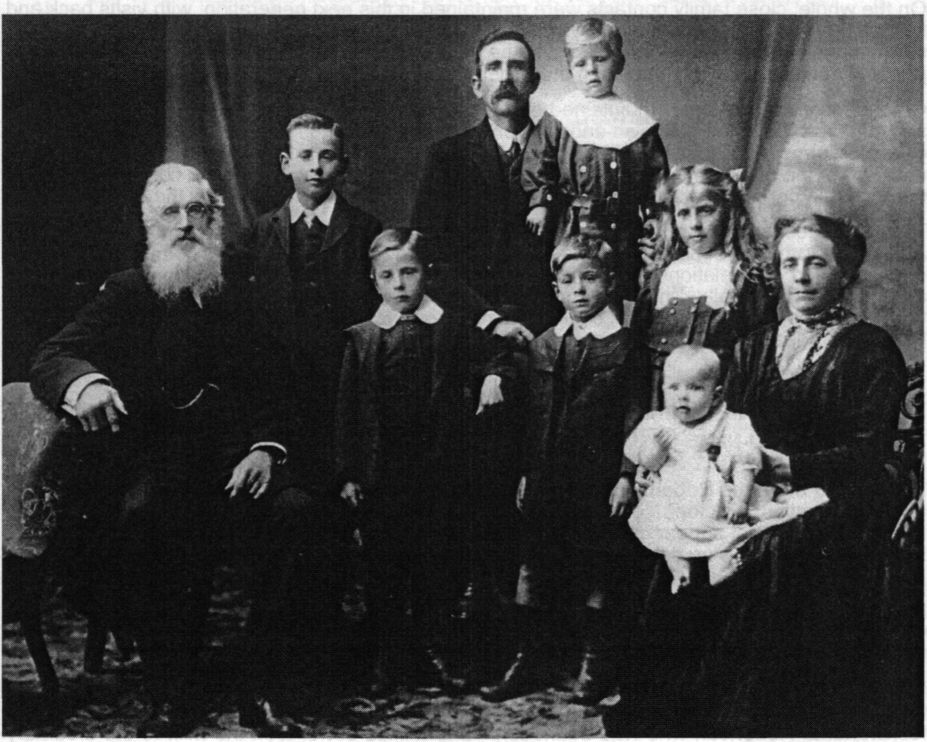

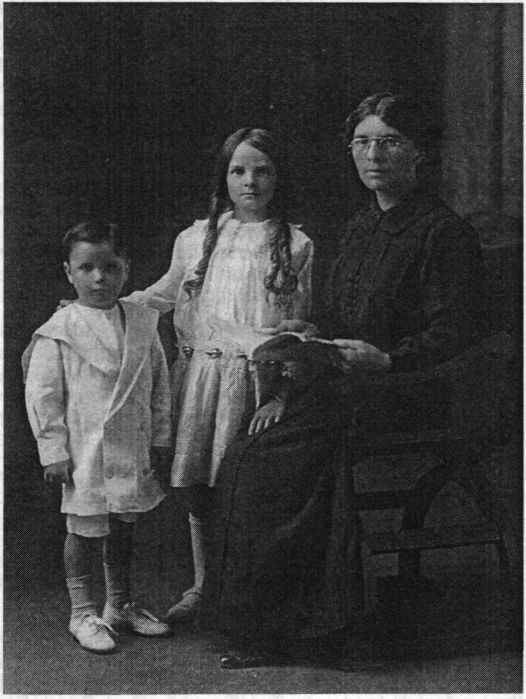

Crouch Family, circa 1911

Left to right: Michael McCue, Arthur, Willie, Edwin Crouch with his arm around Norman, Eddie, Ellie and Barbara (McCue) Crouch holding Clifford.

page 65

As a child of nine, Lottie Robertson was sent north because of a weak chest and she lived with her cousin Barbara for two years. This was at Woomelang and would have been about 1902.

Making a living in the Mallee was not easy and Barbara and Edwin seem to have moved about a lot; Willangie, Brim, and Woomelang. For a time Edwin worked on the construction of the railway line between Melbourne and Mildura, only coming home to his family at Woomelang a tweekends. During this period, when he was working about halfway between home and Mildura, his son Arthur developed diphtheria. There was no train so Edwin walked overnight along the line to get back to his family. Medical facilities were not easily accessible and families had to manage as best they could. Edwin’s mother (Elizabeth Crouch) acted as a mid-wife and was present at the birth of Raymond McLean, whose daughter Margaret, was to marry Barbara and Edwin’s grandson, Ken Crouch, many years later.

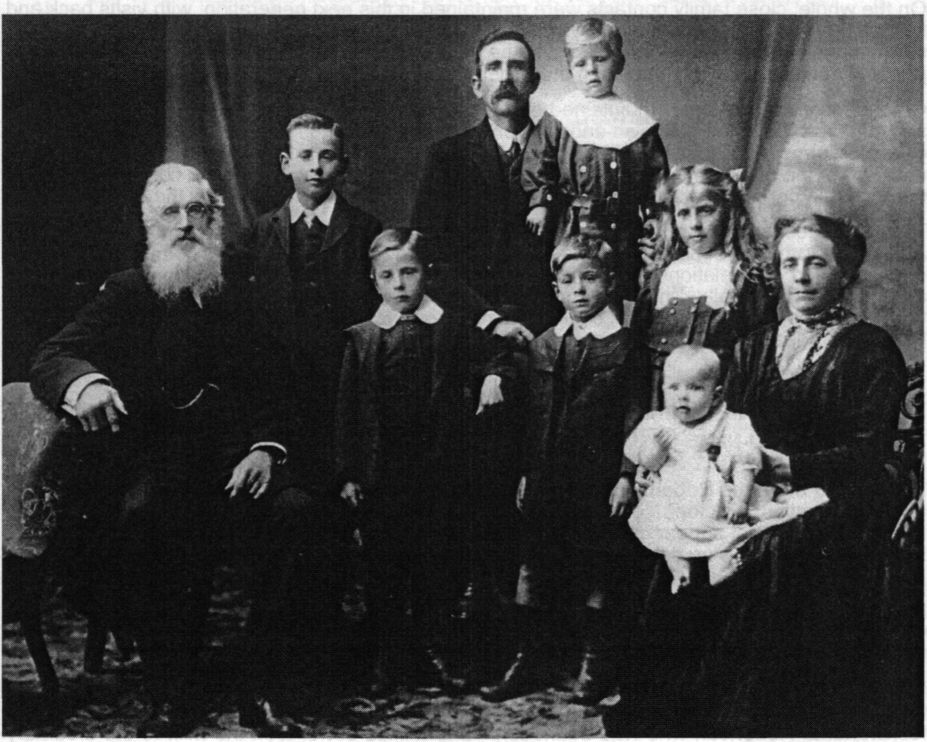

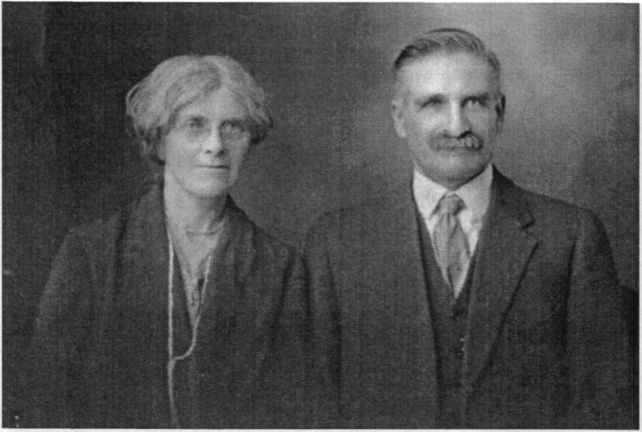

Edwin and Barbara Crouch >

Barbara and Edwin had a farm at Panitya and the three youngest children, Clifford and twins Barbara and Clive, were born there. Michael McCue lived with them at Panitya and died there at the beginning of 1916. Eddie Crouch told his son Ken, “the farm at Panitya was in a ten mile wide strip that ran from the Murray River and NSW border to the Southern Ocean, known as the ‘Disputed Territory’ as both Victoria and South Australia claimed it, the border not being in line with the NSW/SA border for some reason”. 3

The Panitya farm did not prosper. The land was good but the block was not big enough to support an income. Edwin became insolvent and the land was taken off them. Barbara Rogers was seven when they left Panitya. The family was at Cowangie share farming in 1921when Clive was killed, and Ellie was married there in 1922. Edwin continued share farming and as one contract finished, the family would move on to another farm. Over the years the family lived at Karawinna, Walpeup, and at Nadda and Renmark in SA, then Milawa, where one of the boys took up land, and Merrinee North. The land at Merrinee was repossessed by the government for redevelopment, four blocks being combined into larger more viable lots. These were then put up for re-selection. The outgoing farmers received compensation. The family moved to Port Campbell, farming there for a time and helping to look after Agnes’ brother, Arthur, when he was an invalid.

Barbara and Edwin were finally able to retire, buying themselves a house and settling atTurriff, with money left to Barbara through Arthur McCue’s estate after his death in 1938. Daughter Ellie (Ribbons) and son Willie lived near by with their families. After Edwin’s death, Jack Ribbons and his son, Alan, bought Barbara’s house and organized for it to be moved to Sea Lake, where Barbara's sisters Bean and Aggie also lived.

Barbara Rogers describes her father as “a poor man, a battler, a very peaceful man - could have been a journalist or a news reporter - wrote a good hand - wherever he went he contributed news items to the local paper - which he received free in return.” 4 Edwin was a lay preacher in the Methodist Church and would conduct services when no minister was available. He was a big man and put on weight as he aged. He experienced prostate trouble and died at the Mildura Hospital in 1950, aged seventy-nine. He is buried at Woomelang.

page 66

Among her many skills, Barbara included knitting and crochet. Barbara Jnr remembers her mother staying up all night to crochet a pair of booties for a baby to wear to church the next morning.

In later life, Barbara lived with Barbara Jnr and Stan Rogers at Sea Lake. I have been told that unlike her sisters Aggie and Bean, who had reputations for being cantankerous and difficult in their old age, Barbara was always patient and easy to live with. She maintained her energy right up to the end of her life and was always gracious. We have the story of her attendance at her 100th birthday reception, which was held in the town hall at Sea Lake. Not wanting to tire her, the family suggested she wait until the guests were assembled before they took her to the party. She however had other ideas, ‘Haven’t I taught you girls any manners, we should be there to greet the guests when they arrive’. Using a similar argument, she would not go home until the last guest had departed. During the proceedings a local dignitary stood holding the letter of congratulations from the Queen, while he made a long drawn out speech. Prompting him on, Barbara said, ‘Hurry up and give it to me’. 5

Next morning Clive Crouch, who had been staying with his Auntie Ellie, wanted to say goodbye to his grandmother before leaving. He waited until about 9.30 a m. because he didn’t want to go round too early. He found Barbara sitting at the table with a cup of tea and a couple of dry biscuits. 'Gee Grandma,you’re up early, having breakfast already!’‘ Breakfast boy! This is morning tea. I’ve been up and made my bed and done the dishes’. Everyone else was still in bed. 6

Another story tells of Barbara getting a lift to town. After completing her business she was returning to the car when she saw, from a distance, the driver getting into the car. Frightened she would be left behind she lifted up her skirts and ran. The sight of an elderly Barbara running down the street with her skirt hitched up caused much amusement amongst the locals.

Perhaps the most delightful story about Barbara is this one told by Alan Ribbons:“Grandmother lived with her daughter Mrs Barbara Rogers and Stan Rogers [her] son-in-law. Now Stan had a little dog called Joe. One day Stan said, ‘Now Grandma - when I die I want you to see that my little dog Joe is shot and put in the grave with me.’ Grandmother’s reply, ‘Oh is that so. What happens if your dog dies first, do we shoot you and put you in the grave with him?’ Not too bad for a 102 year old lady. Grandmother said she got no reply.” 7

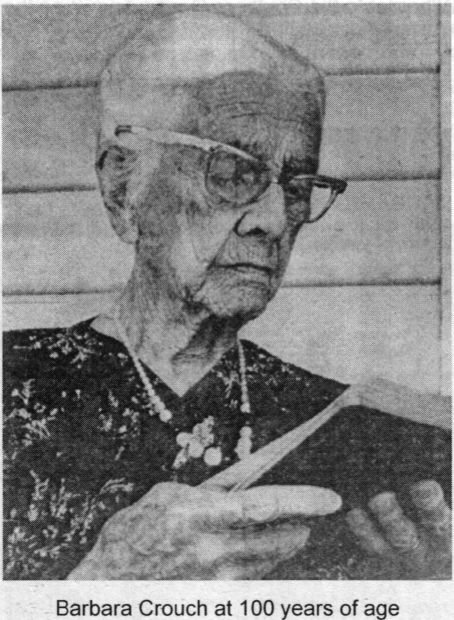

Barbara died at Sea Lake on 1 November 1976, at the age of 105 years and 9 months. She is buried at Woomelang. There are a number of Barbara’s pieces of wisdom recorded in Appendix 5, and I have copies of newspaper articles published at the time of her 100th and 105th birthdays.

page 67

Robina (Bean) Adie McCUE (1872-1953) - MARRIED NAME LE COUTEUR

Second daughter and second child of Agnes Robertson and Michael McCue, born at Port Campbell in 1872, probably on 3 May. Anyone wishing to obtain a copy of Robina’s birth certificate should be aware that in the Victorian records her name is spelt Reberri Eddy McCue. The file number is 7613.

Bean or Beanie, as she was generally known, was delivered by her grandmother in a tent where the Robertsons lived, while Arthur was building the old stone house. Agnes and Mick were not permanent residents of Port Campbell at the time, but Agnes had returned to her mother for the birth. One story describes Bean’s birthplace as a cave. The tent was in fact pitched for protection in a cave-like structure in the cliff face near what was later the Port Campbell cemetery. This had been formed by the Arthur’s excavation of stone for the house he was building.

Robina is listed as one of the first pupils at the Port Campbell School in 1877. 8 Later (1894) she was the sewing mistress at the school.

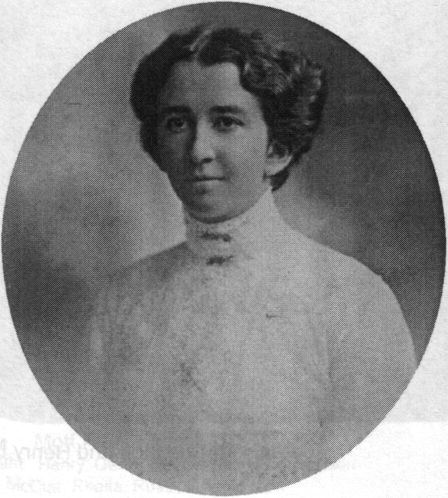

Robina McCue Taken at the time of her marriage to Henry Le Couteur >

Bean married Henry LE COUTEUR (1871-1941), a Boer War veteran, and they had three children, Elma (1904), George (1905) and Stuart (1906). The Le Couteur family came to Australia from the Channel Islands. Henry was an uncle of Archie Mathieson who married Robina’s niece, Marjorie McCue. 9

I do not have a date or place for Bean and Henry’s marriage, but we do know the family moved from the southern coastal area of Victoria to the drier north in about 1910, because of Robina’s asthma. She suffered from severe asthma all her life. Henry obtained work as a ganger for construction of the railway in the Mallee, moving about as the job required.

The family went with him living in makeshift accommodation of tents and lean-tos. Two undated photos, taken at Cowangie, show just how rough this life was. The photos appear to be taken at the same campsite and an estimate of the ages of the children dates the photos at about 1914 or earlier.

To ensure the children would have schooling Bean took in Miss Till, the schoolteacher, as a boarder. Whether this was while they were living in tents or after they built a house is not clear. An extract sent to me from a book called Kow Plains and Beyond, 1849-1988, tells us that Bean and Henry bought three separate blocks of land in Cowangie township in 1913, 1919 and 1921, and the Le Couteurs ran a boarding house on the first of these. “... at lunch time school children would be sent to fetch a billy of tea from Mrs Le Couteur for the teachers’ lunch. Mr Le Couteur was the first railway repairer (ganger) at Cowangie, and also had cattle yards ... He supplied milk to the town”.10 The Le Couteur name appears on the list of contributors for building the first hall at Cowangie in 1913.

Later Henry and Bean lived at Turriff, in a house next to the local hall where there are now tennis courts. Barbara Rogers writes that the families of the three McCue sisters “lived in the same area and had a close relationship. Aunt Robina was witty - glib tongued, but intelligent and extremely loyal. Once Mother [Barbara Crouch] had a kidney disorder and Aunt Bean took her and Clive out to her place and nursed her through it. When we lived at Merrinee - when I was a teenager - Mother had trouble with her nerves, Auntie Bean and Uncle Henry drove straight through the bush from Cowangie in a horse and cart, and Auntie stayed until Mother recovered”. 11

page 68

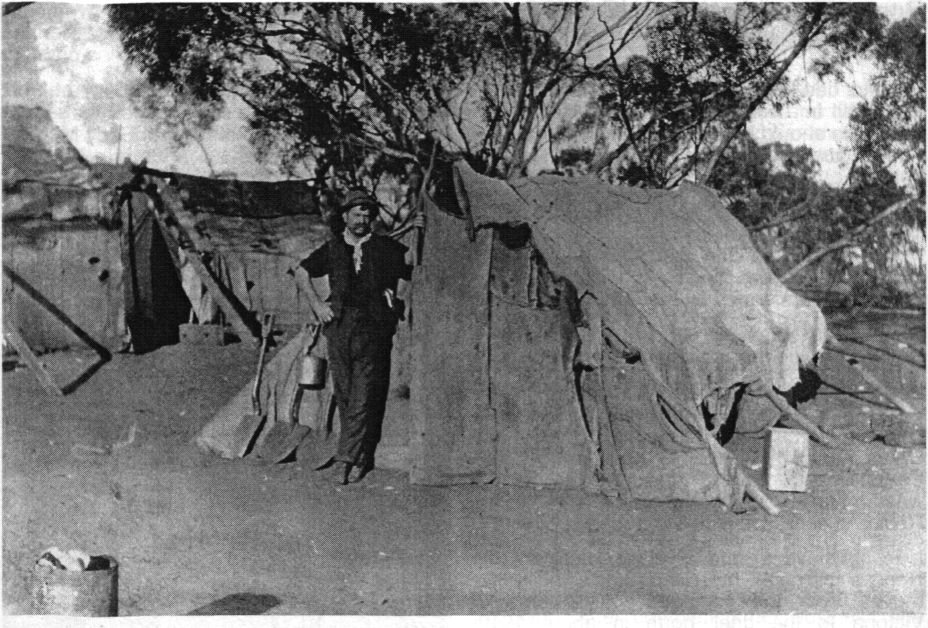

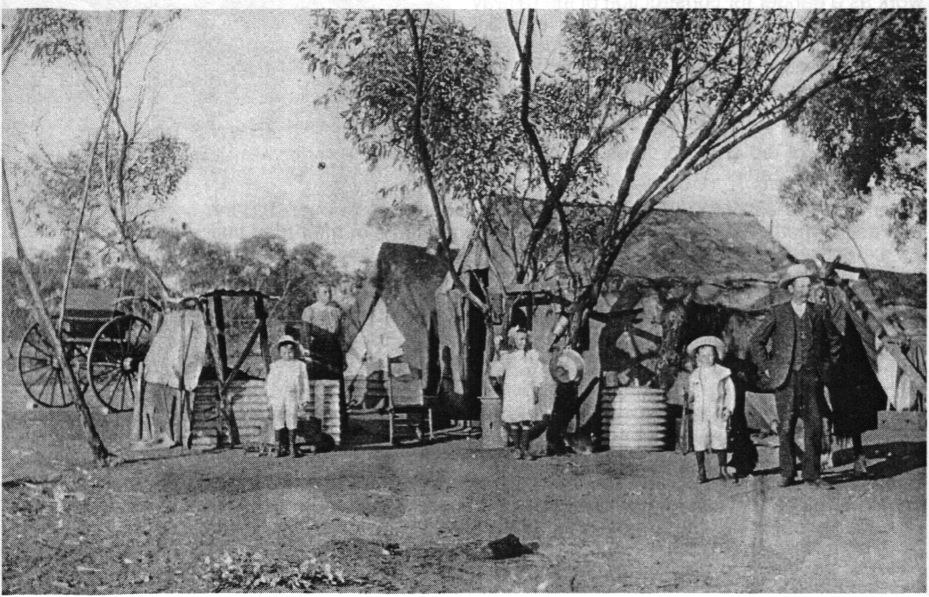

Le Couteur camp site at Cowangie, circa 1914 Henry, dressed in working clothes, stands in front of a tent made out of chaff bags.

Le Couteur camp site at Cowangie, circa 1914. Left to right: Stuart, Bean, Elma, George, Henry. Henry is wearing his good clothes and a fob watch. Bean and the children are also dressed nicely for the occasion, the children with boots and socks, Elma with bows in her hair and the boys with hats. The tent in the first photograph is just right of this scene. Note the horse and gig, the corrugatedwater tank and a corrugated iron and timber construction, which was probably the cooking area. There are tools and household utensils and a little bit of luxury in the form of a cane-backed rocking chair.

page 69

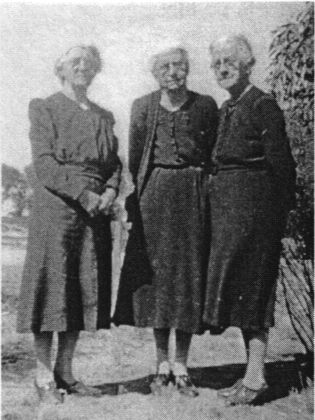

McCue sisters at Turriff Left to right: Agnes, Robina, Barbara >

After Henry died in 1941, son George and his wife Arvon lived with Bean. Bean believed in discipline. Every day when her grand-daughters Lesley and Beanie came home from school she made them sit on the couch for ten minutes without moving, so they would learn discipline. 12

Arvon nursed Bean in her old age. I have been told most emphatically, “She made Arvon's life hell!” (See notes on George and Arvon in Part IV.) Robina died at Turriff at the age of eighty-one. Both she and Henry are buried at Bendigo.

Arthur McCUE (1873-1938)

Arthur was born at Tooliorook in 1873, the eldest son and third child of Agnes Robertson and Michael McCue.13 Arthur was known by a variety of names. Mick or Micky, (as was his father, it was apparently a nickname they both disliked). Norm Chislett knew him as Brooley McCue, and in Barbara Rogers family he was called Jiddy (apparently a contraction of ‘did ya’ or ‘did he’).

I have probably heard more stories about Arthur than any other member of the family. He has been described to me by different people as a loner, difficult, unappreciative, bad tempered, aggressive, domineering, a very angry sort of person, an old devil and a proper dirty old man. Not the best of references, but as you will see, he did have some saving graces. I have not seen any photographs of Arthur but I am told he was like his father in looks and in character. He was a big, strong man. One of his saving graces was a beautiful booming singing voice with its range of four octaves. Alan Ribbons remembers him visiting Willie Crouch at Laang, driving along in a buggy with two grey ponies singing The Wild Rover’ at the top of his voice.14 An appropriate song perhaps, in view of Arthur’s temperament.

When Agnes left Michael in about 1889, she went to live with Arthur on the farm at Smokey Point. Arthur built her a two-room house there. At some stage the house burnt down and many of the family papers and letters were lost in the fire. I have not been able to discover the date of the fire.15 After the fire Agnes lived with her daughter Aggie. Items saved from the fire include a painting of the ‘Stone house’ - smoke stained and the paint slightly cracked. This is now in the custody of Jeff and Di McCue. Gertie Grace has another charred relic from the fire, an extract of birth for Agnes Robertson issued on ‘the twenty second day of March, eighteen hundred and sixty seven’ - three and a half months before Agnes left for Australia.

Arthur lived rough. One of my favourite stories, told to me by several people, is about him cutting bread for visitors, then flinging the remaining loaf at the wall where it was speared onto a convenient spike. This is where he kept the bread. The land, with his hut on, was later bought by Arthur Ward, who used the hut as a pigpen. The land then passed to Gus Ward and when Gus eventually demolished the hut, the 6-inch spikes were still in the wall. 16

page 70

The Lords were one of the earliest families to settle at Port Campbell and Gus tells of an argument Arthur had with William LordJnr, which resulted in Arthur selecting 600 acres of land above the Loch Ard Gorge to spite William. According to Gus, Arthur never used the land himself but fenced it so that William Lord could not use it to run his sheep. Marion Parker however, writes that Arthur used the land for running beef cattle and horses.17 On maps of the area this land is Lot 31, marked in the name of JR McCue.

< McCue’s bullock yard at Port Campbell.

I have not been able to locate a photo of Arthur McCue, perhaps the unidentified man with the rifle here is Arthur.

A different side of Arthur McCue is shown in a story told to me by Port Campbell resident Etty McKinnon, nee Lord, the daughter of Stewart Lord. Etty is convinced that Arthur saved her life when she was six years old in 1930. Her family lived some way past the Port Campbell cemetery, along the present Timboon Road, and on this particulard ay, Etty was accompanying her father in a buggy with two in hand, on a trip to town. When Stewart got out of the buggy to open the gate the horses bolted, taking a terrified Etty with them. There were some men working on the road with picks and shovels and they tried to stop the horses but failed. Arthur was riding up the road from the direction of the cemetery. He jumped off his horse and ‘flung himself at the two horses and stopped them’. 18

Norm Chislett tells us Arthur would sometimes turn up at church when his brother Jack was preaching. Dressed like a swaggy he would sit in the front pew and do his best to embarrass his brother. 19 Marjorie Mathieson describes her Uncle Arthur turning up at her parent’s house when he was ill. When she was about twelve Arthur stayed for six months, ill with high blood pressure:

"He sent me to the grocer for six pounds of dry biscuits to celebrate his birthday. The grocer sent me back to confirm the order. Back I went and brought home the whole six pounds of Uneeda biscuits. He’d kept them in his room and as we went past he’d yell, ‘Have a biscuit’. He didn’t believe in washing as ‘it weakens you’ and wouldn't use electric light 'it makes you hot’. Called Mum [Tot McCue] ‘the foreign woman’. When he got better he rose one morning and left. I didn’t see him again till I was eighteen.

"He would appear on our doorstep in rough clothes with his swag on his back. He would be leaning on the verandah post puffing and panting. Mum nursed him but he was not appreciative and extremely vulgar in his comments. Dad in the finish would not let Mum go into his room and looked after him himself.” On another occasion he slept in Jack’s study - “till he was well enough to travel, and Stuart and George Le Couteur came and took him up north to his sisters." 20

One of Arthur’s nicer traits was his devotion to his mother and he missed her terribly when she went to live with her daughter at Woomelang. He went up to Woomelang and there he suffered a stroke. Keeping in character, Arthur made a difficult patient, shifting between the homes of his sisters Barbara, Robina and Aggie. Gertie Grace remembers, “He came up our way shearing ... and took a stroke. He was months and months off work and lived between his sister Robina in Bendigo and my mother [Aggie] ... but oh he was hard to live with. I said to Mum it was probablybecause of the stroke but she said he had always been like that."21

Arthur had substantial property in the Port Campbell area, some of which he cleared and farmed. He bred and trained ponies and these were much sought after. Gertie Grace mentions that Arthur ‘owned quite a lot of land around the district’ and this was left to his siblings. The town blocks were sold and the money divided between Barbara, Robina, Agnes and Jack. Jack McCue bought out his sisters’ shares in the 600 acres opposite the Loch Ard Gorge. The Ward

page 71

family bought land adjacent to Mima Ward and several lots in town were bought by Marjorie Mathieson and later sold. 22

Arthur McCue never married. There are tales of his amorous and not always welcome attention towards women (including chasing Rheita Mott around the kitchen table until Agnes came to Rheita’s rescue) and a romance with his cousin Margaret Robertson (Robert’s daughter), which her family put a stop to.

In later life Arthur was a diabetic. He died at Eaglehawk, near Bendigo, on 6 February 1938 at the age of sixty-five and as he had requested, he was buried beside his mother at Woomelang. His great-nephew, Tim McCue, has the black tin box in which Arthur kept his possessions. Tim’ sfather, Jeff McCue, has Arthur’s bible. Half of one page is missing; Arthur used it to make acigarette when he had run out of cigarette papers!

Agnes (Aggie) Grace McCUE (1877-1977) - MARRIED NAME MOTT

Fourth child and third daughter of Agnes Robertson and Michael McCue, born at Port Campbell on 28 September 1877.

Aggie attended school in Port Campbell and I have a copy of a Certificate of Exemption from Compulsory Attendance dated 1 April 1892. This is the year, according to Marjorie Mathieson, Aggie was working as a domestic in a doctor’s house in Melbourne, however Gertie says her mother never worked in Melbourne and this job would have been in Geelong.

Suffering from chest trouble, Aggie was advised by a doctor to go to a warmer climate. She went to the Victorian Mallee, where her sister Barbara was living at Woomelang, and it was here she met her future husband. Aggie was a good tennis player and the couple met at a young people’s gathering. Both Aggie and Barbara had accents that have been described to me as Scottish, but were perhaps a mixture of their parents Shetland and Irish accents.

Aggie and Henry John MOTT (1878-1947) were married in the Galiquil East Public Hall on 24 June 1903. The service was performed according to the rites of the Baptist Church, with Thomas Nichols the officiating minister. Witnesses were the bride’s brother, Jack McCue, and Setelia Adelaide Mott. Henry was the son of John Mott and Mary Maria Sinai 23 Copeland, and hewas born at Telangatuk. Like his father, his occupation is described as farmer. The Mott family were involved in whaling out of Port Fairy in the 19th century. Some of Henry’s brothers moved to Western Australia and there are Mott relations in that state.

Aggie and Henry had five children, two girls followed by three boys. The youngest boy, Harold Henry, lived for two months in 1917, dying beside the road near Lacelles as his parents were attempting to get him to the Hopetoun hospital. They had already taken him to Sea Lake but the doctor was away and they returned home before going in the opposite direction to Hopetoun the next day. Henry had to travel on to Beulah to get a coffin, before the group returned to Woomelang for the burial. “All this travelling was done by the same pair of horses and it rained for most of the 3 days. The road was just a quagmire. The horses being very leg weary, lay about for 3 days, as the water was sometimes up to their bellies in some places.” 24 I am told a song was written about this sad event, but I have not been able to obtain a copy. An autopsy discovered the child had a ‘hole in the heart’ and doctors were surprised he had lived so long.

The Mott’s eldest boy, Mervyn, died of Bright’s disease at the age of twenty-five in 1933. He is buried in Melbourne’s New Faulkner cemetery. The surviving children were Gertie (1904), Rheita (1907) and Russell (1911).

The Mott family had farms at Galiquil East and Henry was at first share farming there with his brother Alf. Henry sold his share and he and Aggie moved to a farm at Kaniera (now known as Culgoa). When this farm was sold, they went to another farm at Keith in SA. Finally in 1910, they selected land near Turriff and lived at Gama East for the rest of Henry’s life. As well as

page 72

contributing to the family farm, Aggie had a property of her own. ‘It’s my block and money from the wheat goes into my bank.’ 25

contributing to the family farm, Aggie had a property of her own. ‘It’s my block and money from the wheat goes into my bank.’ 25

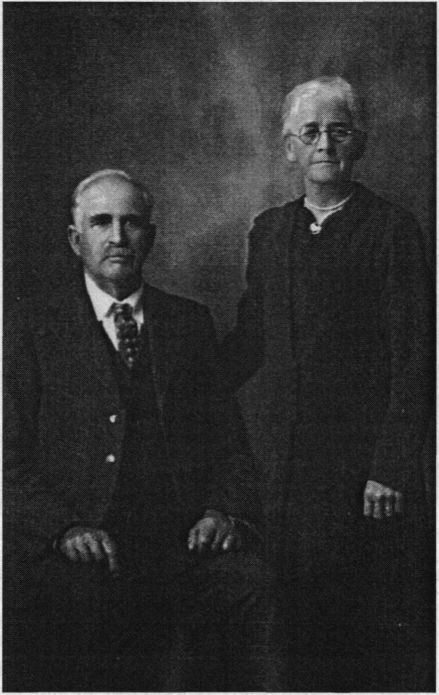

Mott Family, circa 1913 Left to right: Henry, Gertie, Mervyn, Agnes RobertsonMcCue, Rheita, Russell, Aggie Mott >

Gertie writes that Aggie “was a wonderful mother and I have lovely memories of her loving kindness to us as children and always as teenagers she wanted the best for us (her childhood was not the happiest). My father was a lovely patient man, supported her in all that she said or did, for the good of his family. So what more could you wish for.” 26

Like so many other Robertsons, Aggie was a singer (a soprano) and played the organ for church services. Alan Ribbons tells us that in church Aggie would sit in the front pew, leading the singing half a bar ahead of everyone else.27 She encouraged her children’s musical ability with music lessons. Rheita was given an autoharp and Mervyn a violin. After Aggie’s death Gertie inherited the family piano. She still has the piano, as well as Mervyn’s violin. Gertie’s daughter, Margaret Powell, has the autoharp.

Like so many other Robertsons, Aggie was a singer (a soprano) and played the organ for church services. Alan Ribbons tells us that in church Aggie would sit in the front pew, leading the singing half a bar ahead of everyone else.27 She encouraged her children’s musical ability with music lessons. Rheita was given an autoharp and Mervyn a violin. After Aggie’s death Gertie inherited the family piano. She still has the piano, as well as Mervyn’s violin. Gertie’s daughter, Margaret Powell, has the autoharp.

Aggie with two of her children. The identity of the children is uncertain, probably Rheita and Russell. >

Barbara Rogers writes, “Aunt Agnes was so ladylike - always wore hat andgloves - even when shopping. She’d come and visit us - Mother and her would talk Gaelic to each other and laugh and laugh. Of course the three girls were very Irish. Aunt Agnes wa sa lovely singer. They were always so hospitable.” 28

Aggie seems to have had an independent and dominant personality. When she went driving with Russell, she would insist on sitting in the front seat while Vivienne sat in the back.

After Henry’s death from a stroke, Aggie lived in a house next to Rheita and Bert Mitchell’s farm. This house had been the Baptist manse at Turriff and was shifted out to the property at some time before the Mitchells moved onto the farm. Rheita’s daughter, Sue, says Aggie came over to sleep at Rheita and Bert’s and used the toilet there, as there was no toilet at Aggie’s house. She came with us to church and when we went visiting to Gertie’s

page 73

Aggie McCue Mott and Henry Mott >

and to Uncle Russ - was company for mum when we were at school or awayand the men out working. It was great when Uncle Jack and Auntie Tot used to drive up from Melbourne in their black Morris and stay a fewdays. Auntie Barb would also come across from Sea Lake. Grandma had a nice garden with lots of rosebushes in it and self sown cosmos, a very colourful sight”. 29

In later life Aggie moved in with the Mitchells, and she expected Rheita to wait on her, which Rheita patiently did. When Rheita could no longer look after her because of her own ill health, Aggie went to live with Gertie and Mac Grace. By this time she was in her mid nineties and with advancing age she had become difficult and demanding. Her great granddaughter, Colleen Barnes, says she was a ‘bit scared’ of Aggie. She would sit in a chair in the passageway and if she wanted anything she would bang on the floor with her stick. “We were too scared to go past her in case we copped the stick.” 30

In later life Aggie moved in with the Mitchells, and she expected Rheita to wait on her, which Rheita patiently did. When Rheita could no longer look after her because of her own ill health, Aggie went to live with Gertie and Mac Grace. By this time she was in her mid nineties and with advancing age she had become difficult and demanding. Her great granddaughter, Colleen Barnes, says she was a ‘bit scared’ of Aggie. She would sit in a chair in the passageway and if she wanted anything she would bang on the floor with her stick. “We were too scared to go past her in case we copped the stick.” 30

Aggie Mott >

In the middle of night she would bang on the bedroom wall and demand a cup of tea or she would want to get up and dressed. This meant Gertie getting up to light the stove and helping her mother to dress. If Gertie refused Aggie would say, ‘There’s no sympathy in you, you’re not a sympathetic person at all. I want to go back to Rheita.’ Gertie writes: “I had to wait to help her drink it [the tea] as her hands were very shaky and it went all over her and the bed. Rheita used to fill a small thermos and she got herself a drink, but when she came to me she could no longer get the thermos open or pour it out into a cup without spilling it everywhere.” Eventually Gertie, who was in her seventies, could no longer cope, “the thing that finished me was lifting her about as she became very weak and could not turn in bed or get up to go the toilet without help.” The family decided Aggie should be admitted the hospital in Ouyen. Aggie protested, claiming ‘Russell wouldn’t let you do this’, but it was Russell who actually took her to the hospital. Rheita died on the 7 May 1977. Aggie died three weeks later, two and a half months short of her 100th birthday.

John Robertson Thomas McCUE (1881-1975)

Fifth child and second son of Agnes Robertson and Michael McCue, born at Port Campbell on 5 May 1881. Professionally he was known as the Reverend Robertson McCue, to family and friends he was known as Jack.

Suffering from asthma, Jack was indulged as a young child and allowed to run wild. He had only three years of broken schooling. As a lad he worked in the bush with his brother Arthur and went shearing with him on the Manifold property at Talinga. Arthur was much harder on Jack than Jack was willing to put up with, and at seventeen he packed his swag and walked out. His sister Aggie was working as a domestic for a doctor in Melbourne (or it may have been Geelong) and the doctor’s wife took Jack in. It was at this time Jack met his future wife Sarah Edith COLLINS

page 74

Sarah Edith Collins >

(1886-1971), known as Tot or Totty, a name given to her by her father when she was a little tot or toddler. Sarah Edith was the sixth child and second daughter of James Collins and Sarah Corfield’s ten children. She was thirteen when she met Jack and they were each other’s only sweethearts. Marriage however had to wait.

Jack moved on to Beulah where another sister, Barbara McCue was ‘helping out’ the William Adie Robertson family. William Adie persuaded Jack to go back to school, and he would sit at the back of the ordinary classes at the local State School. He eventually obtained his university entrance and attended the Victorian Baptist College (1911-1913), while studying Greek and Hebrew at Melbourne University.Having obtained his theological qualifications, Jack become ordained.

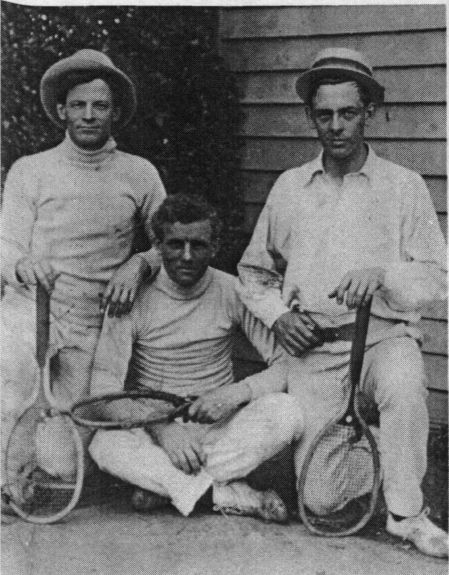

Jack McCue, the sportsman, on the right, with two of his friends. >

Before entering the Baptist College, Jack worked as a home missionary at Normanville, Kerang and in the Wimmera. In the newly developed coal mining district at Wonthaggi, Jack ran the first of his anti-alcohol campaigns. “The ‘Blue Pigs’ were the two-gallon licenses issued to men outside the boundary of the no-license Government town, and the licensees used to sell the beer to the miners. When he [Jack] left, the townspeople - drinkers and non-drinkers - gave him a dinner and a goldwatch.” 31

Jack’s anti-alcohol stand was a reaction to the drinking he had seen in his family as a child. Prohibition, or at least the reduction of alcoho luse, became a life-long crusade for Jack. He must have felt the use of alcohol for medicinal purposes was all right, as in a 90th birthday interview for Melbourne Herald he is reported as saying “alcohol should be available only on a doctor's prescription, like drugs.” 32

After his ordination, Jack married Tot Collins on 8 September 1914. They had three children, Marjorie (1915), John Jnr (1917) and Marion (1922).

Jack’s pastoral work took him to St Kilda (1914), Castlemaine (1916), Moreland (1922-24) and West Preston (1931-37). Between 1924 and 1931, Jack took up a position with the Anti-Liquor League and after 1937 he worked with the Local Option Alliance and later the Victorian Temperance Alliance, of which he was the secretary for many years.

page 75

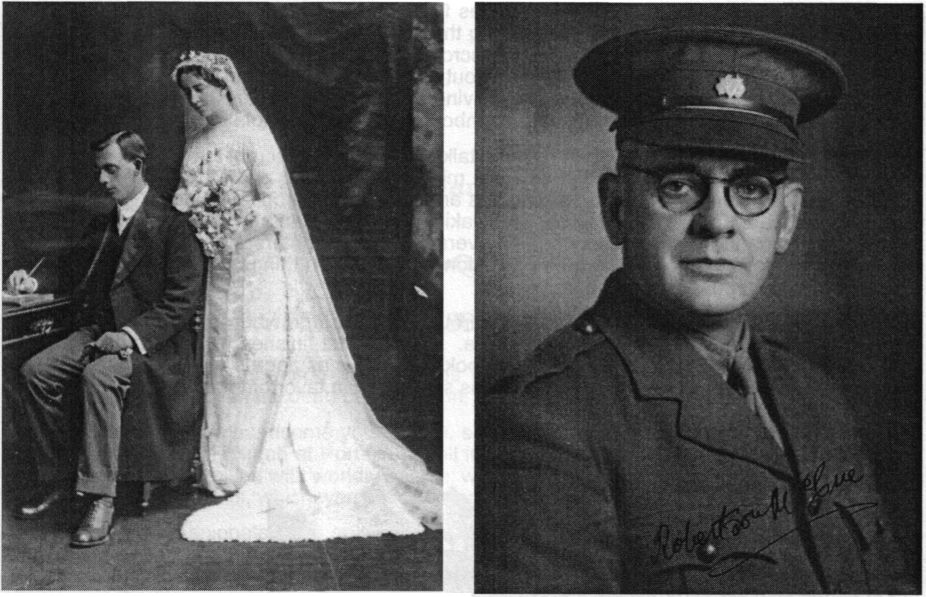

Jack McCue and Tot Collins. Wedding photograph, 8 September 1914.

Jack McCue in uniform as a YMCA chaplain during World War 2.

Grandson Jeff McCue recalls that Jack always wore his clerical collar, even when relaxing. He was “a big strong man who could carry a bag of wheat on each shoulder”. He carted hay with Jeff and Alden when he was over seventy, ‘throwing them up four high’. “He was good to my brother and I and to Mum ... a nice bloke.” 33

Jack was very much a family man and kept in close contact with his sisters and brother, his cousins, and their families. As executor of his brother Arthur’s estate, Jack was responsible for the sale of Arthur’s property and dividing the proceeds equally between himself and his three sisters. Jack bought the 600 acres near the Loch Ard Gorge. Jack’s daughter Marion writes that the land was poor and Jack “sought the help of Victorian Agriculture to test the soil and suggest what was needed for good pasture. This advice was willingly given and Dad proceeded with obtaining local knowledge and prepared and fenced experimental plots. A local farmerand his son were employed to carry out this work. Good results were obtained and young beef cattle purchased. They did well. More ploughing and appropriate super spread. I spent many holidays there working with my Mum and Dad clearing, ploughing, harrowing and spreading super. We had purchased a Bren Gun Carrier, 34 minus its turret, a blade on the front. Tractors were unobtainable after the War.” 35

Jack sold the property in the 1950s and with the proceeds, he and Tot were able to purchase a home for their retirement. The house had a separate flat that could be let to tenants. The Baptist Church provided no superannuation for its ministers.

Jack had a Morris Oxford motorcar and this car comes into several of the stories I have been told about him. Jeff McCue again, “He rang me up. ‘Can’t drive it any more Jeff, I’m ninety-two, they won’t let me drive it any more. Could you come down and pick it up?’ Di and I went down and drove this old unroadworthy black Morris Oxford from 2 Wills St, Deepdene down to a little farm at Curdie Vale. He wanted to have a last drive. Down the road, Di and I in the back seat. He bipped the cars and up the side of the creek. I said ‘Cripes you’re cutting it close grandpa.’He said, ‘Paints thick boy, paints thick’.” 36

page 76

Another story involving Jack and his car comes from Ken Crouch. “We once took Uncle Jack McCue up to Sea Lake to see Grandma during the 1970s. He was then in his late 80s or early 90s I think. As we passed a train, he looked across and said, ‘Ever hit one of those things, my boy?’ I said ‘No Uncle Jack’ and he told me about hitting a train at a level crossing at Eaglehawk (near Bendigo) years before, when he was driving a Morris Oxford car. He said - ‘I hung onto the steering wheel; Aunt Tot hung onto the dashboard. It took the whole front off the car’.”37

Tot and Lottie Dickins used to spend hours talking to each other on the phone. Actually it seemed to us Dickins kids it was Tot who did most of the talking and Mum would sit knitting, the phone propped on her shoulder, saying yes and no in the appropriate places. One time she went to sleep while Tot was chatting on, and waking up with a start she hoped the next yes and no she put in was the correct response. Conversely, Tot’s daughters thought it was Lottie who did most of the talking. Tot left us a bit of wisdom to help when things are not going quite right - ‘Tack tired onto tired, and start again.’

Tot and Jack were living in retirement at Canterbury in Melbourne when Tot died in 1971. Jack died four years later at the age of ninety-three. John Sorrell finishes his 90th birthday article about Jack by saying, “The old man is 90 but looks 70. He is as aggressive, as pugnacious and as clear-headed as ever. And that, I suppose, is something in favor of total abstinence.”

McCue siblings, circa 1950

Left to right: Tot, Bean, Barbara, Jack and Aggie >

1 Letter from B. Rogers, September 1999

2 Quotes from M Mathieson are taken from letters and interviews in 1998-2000

3 Letter from Ken Crouch, September 2000. This confusion about the border is apparent in some of the stories I have been told, which describe towns close to the border as being in South Australia when they are actually inVictoria.

4 Letter from B. Rogers, June 2000

5 Told to me at a family gathering in Portland, April 2000

6 Interview with Clive Crouch at Portland, April 2000

7 Letter from A Ribbons, January 2000. This story was also told to me by Clive Crouch.

8 J. Fletcher, “The Infiltrators”

9 See Appendix 3 for details of the relationships between the Robertson - McCue - Le Couteur - Mathieson - Crouch - Croft families. Takes a bit of working out!

10 R Wilson, Kow Plains and Beyond, 1849-1988, p.76

11 Letter from B Rogers, June 2000

12 Interview with Heather Richards nee Le Couteur, April 2000

13 Stories about Arthur come from a number of sources including Gertie Grace, Marjorie Mathieson, Marion Parker, Jeff McCue and others referred to in the footnotes.

14 Letter from A Ribbons, February 2001

15 I have been told of at least two fires involving the destruction of family effects and it is difficult to work out which one is which, as I have no dates or definite locations. Jack Fletcher records that bush fires swept through the district when the forest was still standing and some settlers lost everything.

16 Interview with Gus Ward, April 2000

17 Letter from M Parker, 29.8.2001

18 Interview with E. McKinnon at Port Campbell, April 2000

19 Interview with Norm Chislett, April 2000

20 Interview with Marjorie Mathieson, March 2000

21 Interview with Gertie Grace, April 2000

22 Information from Gus Ward, Marjorie Mathieson and Marion Parker. Marion was involved in preparing the probate and transfer documents while working as a law clerk for Maurice Black and Co.

23 I have been given several different spellings for this name but Gertie Grace tells me this is the way it is spelt on her grandmother’s gravestone, letter from G. Grace, 10.2.2001

24 Taken from a short piece called 'A Very Sad But True Story’ written by Gertie Grace

25 Interview with Alan Ribbons, April 2000

26 Letter from G. Grace, July 2000

27 Interview with A Ribbons, April 2000

28 Letter from B. Rogers, June 2000

29 Letter from Sue Boyd, 16.7.2000

30 Interview with Colleen Barnes, April 2000

31 Newspaper cutting, dated 6.5.1961. The article is under the heading ‘In the Churches’ and marks Jack’s 80th birthday. The name of the newspaper is unknown.

32 Interview by John Sorrell published in the Melbourne Herald newspaper, 7.5. 1971

33 Interview with Jeff McCue, April 2000

34 After World War II another relation, James Norman Robertson in WA, was employed in converting Bren Gun Carriers for farm use. See Chapter 22.

35 Letter from M Parker, 29.8.2001

36 Interview with Jeff McCue, April 2000

37 Interview with Ken Crouch, April 2000