The Folk from the Wind Wound Isle > Chapter 18 : The Children of Robert Robertson and Mary Jane Cairns

page 101

Stories related to me by family members suggest that Robert and Molly’s household was a dynamic one, full of strict rules, yet full of change as people came and went. Life flowed around Robert’s evangelical work. Molly supported him in this but occasionally it meant hard times. Robert would go away on one of his tent missions and Molly had to make ends meet as best she could, often relying on charity to support herself and the children still at home. Margaret Haine supplied a ditty that Robert used to sing: 1

When the purse is rather slim

And the bills are coming in

Then Satan needn’t grin

Alleluia

I’ll be strong in the belief

That the Lord will send relief

He’s a never failing chief

Alleluia

Barwon House, circa 1912

Stuart Robertson Jnr gives us a picture of family life at Barwon House at the beginning of World War I, when he, his parents and his sister Mary lived there for a time:

“There was always a most interesting life style going on, with Grandpa, Auntie Nan - who round about that time was Secretary [of the Western Australia Women’s Temperance

page 102

Union], She used to wear a white enamel badge tied in a bow with WA and some description of the Women’s Temperance Union. Aunt Margaret used to swan around as she usually did when she was mistress at Geelong Grammar. Uncle Stuart was always there and he was supposed to be my guide, philosopher and friend. Grandpa, who seemed to be in and out of the place quite frequently - away on preaching rounds - and Grandma was my absolutely sole help.

“One time there I apparently did something that aroused the ire of my father and I scuttled away and escaped him. He went through the house looking for me and couldn’t find me for the simple reason Grandma, in her great big long black skirt, had me hidden under her skirt in between her legs.”2

Prayers in the house, night and morning, were led by Robert if he was home, and by Molly if he was away. The prayers were apparently long and tedious for small children. Stuart tells us, “it was the done thing to get down off your chair and kneel with your head resting on the seat of the chair”. He can still call to mind the smell of the chair leather. His sister Mary recalled having to stay perfectly still and the roughness of the horsehair couch filling. Her grandmother, taking pity on her, would surreptitiously slide her skirt over the seat so that Mary's face rested on the skirt rather than the horsehair.3

According to Stuart, everyone came back to Barwon House sooner or later and would “stay there for some length of time. They would come home because they had no place else to go.”4

At the back of Barwon House was a three-storey timber building where shearers and farm hands used to stay. Stuart was only allowed to go there if his Uncle Stuart accompanied him. From here the land sloped down to the Barwon River. Nearby lived a family known as the Windmill family. Stuart believes they were something to do with the manufacture of leather, and they were also involved with the ‘Christian invasion’ of New Guinea. They were building a motor launch in

Robert Robertson Family

Taken at Barwon House at the time of Lottie Robertson’s wedding to Sid Dickins on 4 January 1916.

Left to right, standing: Arthur, George, Josh, Glady, Stuart. Seated: Lottie, Rab, Robert, Molly, Nan, Maggie.

page 103

their yard as part of this involvement. Everyone from round about, including Stuart, came to watch the boat being launched. It was rolled down to the river on logs.

Two stories about the family come from Margaret Haine.5 Back in those days there were varying grades of butter. For everyday the family used the cheapest grade of butter, but visitors were served a better butter. One time when a visiting dignitary was being entertained, there was a lapse in the conversation. Clearly heard in the ensuing silence was one of the boys saying to his brother, ‘Hand me the bad butter’.

On another occasion Nan was standing looking out of a window and described to others in the room with her, the approach of a young man and women coming from opposite directions across the paddock behind the house. Eventually the couple met and kissed. Lottie was too small to see out the window and was desperately trying to drag a chair across so she could climb on it and see out, exclaiming all the time that she did not believe Nan, for such a thing could not be happening.

Robert (Rab) ROBERTSON (1875-1961)

First child and eldest son of Robert Robertson and Mary Jane Cairns, born at Port Campbell. It was accepted in the family that Rab was born on 8 August 1876, however the Victorian records show he was actually born in 1875, four months after his parents marriage. Whether the more respectable date of 1876 was perpetrated by his parents or Rab himself we shall never know. It does however tell us something about the mores of the time.

As a small child, Rab went out with his father when Robert was building stone fences. Rab’s job was to find the small stones that fitted in between the larger stones, which made up the walls.

Rab probably received his primary and secondary education in Geelong. He had a fine singing voice and photos of him as a young man show him to be dark haired and good looking. He went on to train for the Baptist ministry at the Baptist College in Queensland and was among the first group to graduate from the college.

Fanny Daniell and Robert (Rab) Robertson

When his brother Josh was preaching at the Baptist Church in Gympie, Rab made a trip to see him. While there, Josh introduced him to Fanny Jane DANIELL (1873-1961). Fanny was the youngest child of William Jeremiah Daniell and Jane Jackson, who ran a haberdashery and drapery shop in Gympie. She was a student teacher and organist at the Congregational Church. Because she wore glasses Fanny was known to her pupils as ‘Fanny four eyes’. She was partially deaf, a disability which became worse as she got older. Rab and Fanny were married in Gympie in 1907.

page 104

Brothers Rab and Josh Robertson in Brisbane >

Rab’s first ministerial appointment was to the Sandgate Baptist Church and it was at Sandgate the couple’s two children, Mary and Stuart, were born in 1908 and 1911. In 1910 when Rab’s cousin Miriam Robertson married David Lawson at the Beaudesert Baptist Church, Rab gave the bride away. On his departure from the Sandgate church, Rab was presented with an illuminated address by the congregation. The original of this is now in the collection of the Brisbane Baptist College.

Leaving Sandgate in 1914, Rab moved his family to Victoria, where they lived at Barwon House in Geelong with Rab’s parents and other members of the Robertson family. The details of this period are unclear but it seems Rab had no church appointment in Victoria until called to the Elsternwick Baptist Church in about 1916. Prior to the move to Elsternwick, Fanny went back to her parents in Gympie. Whether Fanny intended this to be a temporary or permanent separation is not known. Richard was told by his mother Mary, that she was seven at the time, and she wrote a pleading letter to Fanny asking her to come back and Fanny did return.6

When the ministry at Elsternwick finished, the family moved to a house called ‘Helen’s Lea’ at Ripponlea. Stuart remembers this as a fine two-storey house that had been built by a Judge Hood. It overlooked vacant land and there were few other houses about. From the top floor there was a view out to Port Phillip Bay, Point Ormond and St Kilda and at night they could see the lights of the city. The house is now part of Shelford Girls Private School. Rab was called to the Sale Baptist Church. Fanny and the children continued to live at Helen’s Lea for a period before joining Rab in Sale. The family lived in Sale for seven years, returning to Melbourne in 1928 and again residing at Elsternwick. Rab then worked for a time as an itinerant preacher with the Victorian Baptist Union. His daughter Mary would sometimes accompany him on these tours of duty, while Fanny and Stuart, who was attending Melbourne High School, remained at Elsternwick.

Rab's last calling was to the Kyneton Baptist Church from 1929 to 1935. Rab’s brother George was the Presbyterian minister at Tylden, a short distance away from Kyneton, and the two families would get together for picnics, and the brothers would go fishing together. In photos recording these occasions Rab is always dressed in his clerical garb of black suit, ‘dog collar’ and Homburg hat. It was at Kyneton that Rab bought his first and only car. In Sale he had had a horse and jinker but prior to that all his pastoral work had been carried out on foot.

The time at Kyneton finished badly. Rab did not get on well with the church council and finally had a serious argument with the church secretary. Stuart believes his father was blackballed with the Baptist Union and Rab did not receive another appointment. Stuart describes his father as conservative in his work but good at mixing with those who had nothing to do with the church. When I asked Stuart what Rab did in his retirement his answer was - “Nothing, he did nothing!”

In retirement Rab and Fanny lived at 10 Ormond Rd, Ormond until 1961. They then moved to a cottage on the property at Vermont belonging to Mary and her husband Sid Dickins. There, Mary could look after them. Fanny was by this time blind as well as deaf. Finally the couple moved to a nursing home and they died within six weeks of each other, Rab at the age of eighty-six and Fanny at the age of eighty-eight years.

Anne Adie ROBERTSON (1877-1958)

Born at Port Campbell on 28 July 1877. Always known as Nan, she was the eldest daughter and second child of Robert Robertson and Mary Jane Cairns.

Like so many other members of the family Nan worked as a music teacher. She had a close friendship with her cousins Mime Robertson and Frances Robertson and was Frances’ bridesmaid when Frances married Henry Saunders in 1903.

Nan was the secretary of and organizer for the Women’s Temperance Union in Victoria and later in WA. This was the leading women’s organization of its day, radical in outlook, working for female suffrage and dealing with other feminist issues, including its better known campaign against alcohol and the effect of alcohol on family life. Nan went to America for the WTU in 1922

page 105

and on her return she visited her cousin Frances (Robertson) Saunders in Tasmania. She was in WA at the time her brother Arthur and his family were living there in the 1930s.

Nan Robertson with her cousin Willimina Robertson — Anne Adie (Nan) Robertson

Lottie tells us Nan returned home to live with her parents during the Depression because she was unable to get work, and stayed on to look after them in their old age. She was unmarried and had no issue. She supplemented her income by doing beautiful handiwork and I have a well-worn rug she crocheted for me as a child and a shawl she made for my mother. After her parents died, Nan stayed on in the family home at Belmont which she shared with her brother, Stuart.

Second son and third child of Robert Robertson and Mary Jane Cairns, born at Port Campbell on 11 May 1880.5

The family moved to Geelong where Josh received both his primary and secondary education, the latter at the now defunct Central College. He qualified for matriculation at the age of fifteen. Looking for work and having no money, he walked overnight to Melbourne, a distance of some 70 km, to answer an advertisement for a job, only to find the position had been filled before he got there. A relative lent him the money to return to Geelong by ship. He then found work with the Geelong Gas Company.6

About 1900 Josh went to Queensland and worked as a Home Missionary in the district around Roma and after that at Sandgate (1903-04). He attended the Queensland Baptist College where his brother Rab also studied, qualifying as a Baptist Minister and working with the Evangelical Society of Australia. While in Queensland, Josh met and married Josephine (Josie) HOGAN (1875-1939), the daughter of Joseph Hogan, a sanitary contractor, and Anna Maria Ness. Their only child Rutherford Ness Robertson was born in Melbourne in 1913.

In 1909 the couple moved to Melbourne where Joshua was appointed to various parishes; South Melbourne (1909-12), Footscray (1912-13) and Brunswick (1913-17). During and after the First World War, Josh was a chaplain with the Citizen’s Military Forces. In 1917 he enlisted for active service with the Australian Expeditionary (Imperial) Forces. He served as a chaplain in France for two years. While in France Josh made a trip to see his brother Gladstone, who was serving in the AIF, only to find Glady had died from wounds sustained in action the day before Josh got there.

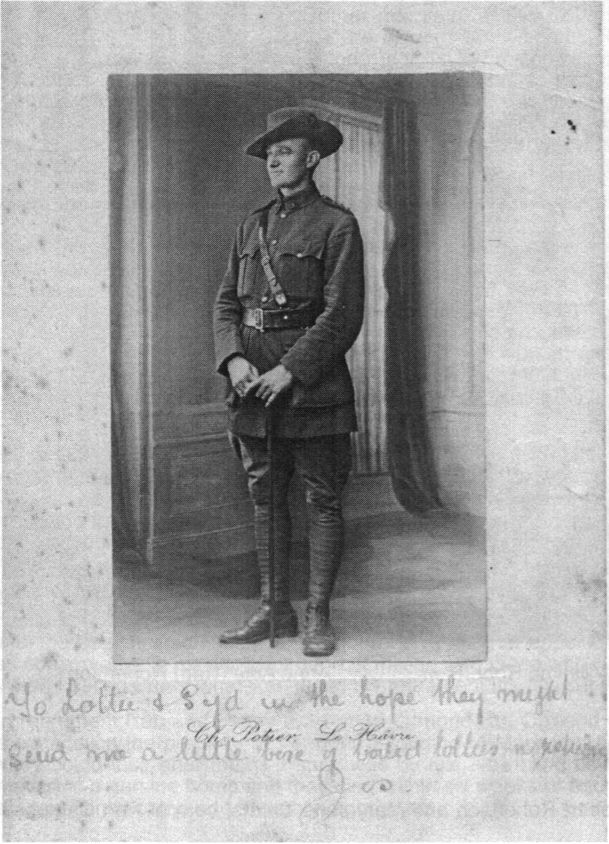

< Joshua Robertson

Josh sent this post card to his sister Lottie from France during World War I and it shows Josh in uniform as an Army Chaplain.

On his return to Australia in 1919, Josh was appointed to the Canterbury parish in Melbourne and was there until 1926. During this time Josh studied for and obtained his Bachelor of Arts from Melbourne University. The family moved to Christchurch in New Zealand where Josh was Minister at the Oxford Terrace Baptist Church. While in Christchurch, Josh obtained his Master of Arts from the Canterbury College, as well as a Diploma of Social Science. Returning to Australia in 1930, he was called to the Petersham Baptist Church in Sydney and served there until 1946.

Josh’s son Rutherford describes his father as an “evangelical type preacher in the strong family tradition. He would call for people to announce that they had accepted the Lord, people would come out the front and a prayer would be said over them. In parallel with this he had a very strong belief in the social responsibility of Christianity. He was way ahead of most of the preachers of his time in this respect.”7 Rutherford also tells us that his father was able to have divergent views on various issues with other people, but still remain friends with them.

It seems however that Josh got into trouble with some of his parishioners for his interest in politics and his concern about social issues. These people thought he should give all his time to preaching the gospel and the saving of souls, and not waste time on questions of whether the community was behaving properly. However the more his parishioners objected the more determined Josh became to continue his involvement.

In May 1937, the Rev Joshua Robertson is quoted as saying: “A great deal of confusion exists with regard to the relationship that there is between the teaching of Jesus and the application of

page 107

that teaching to the problems that face organized society in its political, economic and general social movements”.10

Joshua and Josephine Robertson Christchurch, New Zealand circa 1929 >

Josh was a keen sportsman, playing tennis, cricket and football (Australian Rules), captaining the Queensland State side in the latter sport in 1906. During his association with the army as a padre he used to referee boxing matches. His other interests included membership of a Masonic order and of the Royal Geographical Society. He was a life governor of the Melbourne General Hospital. In March 1941 he was awarded the Australian Efficiency Decoration, as Chaplain 2nd class for his service with the Australian Military Forces Eastern Command.

Josie died in January 1939 following an unsuccessful operation. The next year Josh married Jessie Walters COLLINS (1883-1963). On the marriage certificate, Jessie is described as spinster. The officiating minister was Josh’s brother Rab.

< Joshua Robertson and friends:

Robert Rutherford, Josh, Josie Robertson and friends on a ship from New Zealand, circa 1930

Grandnephew Richard Dickins gives us two stories about Josh in his later years." When Richard was in his last year at high school, Josh came with Richard’s mother, Mary, to the school speech night. He insisted on bringing with him a small case containing his academic robes just in case he was asked to go up on stage. With some difficulty, Mary persuaded him to leave the case in the cloakroom.

When Josh was eighty-seven or eighty-eight he had to re-sit a driving test to continue with his driving license. He was very proud of the fact that he got 100% for the test and the policeman who tested him said he wished some of the younger drivers could drive as well.

After his retirement Josh continued to assist for short periods at various churches in Victoria, South Australia and the ACT. Jessie died in 1963, and Josh moved to Canberra to be near his son Rutherford. Josh died in Canberra at the age of ninety-one. He is the longest living person in Robert’s line up to the time of writing and I think he would like holding that record!

Arthur ROBERTSON (1883-1948)

Arthur ROBERTSON (1883-1948)

Fourth child and third son of Robert Robertson and Mary Jane Cairns, born at Darlington on 12 December 1884.12

Pixie Robertson tells us that as young boys, her father and his younger brother Glady were inseparable and ‘bits of tear-aways’. Like their Shetland ancestors they used to go looking for birds nests up and down the cliffs at Geelong. Their father was often away and their mother was busy with domestic duties or attending to people who came knocking on the door looking for help, so Josh was given the responsibility of keeping an eye on his younger brothers. One of Arthur and Glady’s tricks was to fill a round cocoa tin with lead sinkers and roll it over people’s bare toes. Josh got into trouble about this one night and was ranting and raving about the two boys. Glady was going to roll the tin over Josh’s foot but in his excitement he threw it instead and hit Josh on the back of the head. After this Arthur would refer to Josh as ‘Sneaky Patchy Baldy Head’.

Josh attended College but the younger boys went to the State School. Glady wagged school for quite a long period, spending his time working in the Chinese market garden. Covering up for Glady at school, Arthur told tales about Glady being sick - being better - then worse. His teachers were very concerned. One day when Arthur was in the street he saw the State School Headmaster coming down the street and Josh going up the street. He decided to remove himself and hid in the blacksmith’s shop. “And how’s the poor little lad?” the headmaster asked Josh. The deception was revealed.

Arthur is described as a gentle person, but if he lost his temper, which he did rarely, it was a case of ‘run for cover’. If any of his brothers were bullied at school, Arthur would seek out the bully after school and give him a thrashing.

Receipt for the organ Arthur purchased for use during tent missions

Arthur had a light baritone voice and a number of people have mentioned the joy of listening to his singing. Each person has their own favourite song. Daughter-in-law Lucy Robertson’s was The Boat Song’ by Amy Castles. The song I best remember is ‘The Mountains of Mourne’, and I still get goose bumps when I hear it sung. Arthur was both a violinist and a pianist and he was able to accompany singers no matter what key they chose to sing in.

Arthur would sometimes accompany Robert on his tent missions. I have a copy of a receipt for Arthur’s purchase of a portable organ for £36 dated 1920. This organ was used for the tent mission. Pixie Robertson has the organ.

Rutherford Robertson tells of meeting a church minister who attributed his ‘calling’ to Arthur. When he was a young lad the tent mission came to his town and associating big tents with thing such as circuses the boy went to have a look see. He had his head under the flap of the tent trying to see what was happening when Arthur came walking past. 'You’ve got that far laddie, you might as well go the whole way,’ said Arthur, putting his boot under the boy and pushing him right into the tent. The result was the boy’s conversion and he later became a Baptist minister.13

page 109

Arthur married Lillias Clare CAMPBELL (1888-1965) on 28 November 1914, in the drawing room at Barwon House. Joshua Robertson performed the service and witnesses were George Gordon Robertson and Mary E Tomkinson. On the marriage certificate Clare is recorded as Teacher of Redbank Plains Old.’ and Arthur as ‘Gauger of Barwon House, Marnock Vale, Geelong’. An amusing mistake on the certificate describes Arthur as a spinster. Clare was the third child and second daughter of grazier James Campbell and Louise McGarvie. She was a leap year baby, born on the last day of February 1888. At the time of his marriage Arthur was laying underground pipes and earning the substantial sum of £500 a year. The couple had three children; Ian (1915) was born at Geelong. Pixie (1918) and Rod (1926) were both born at Renmark.

Arthur’s certificate of exemption from army service >

During the First World War Arthur and his brother Glady applied to join the AIF on the same day, 17 January 1916. Glady was accepted. Arthur was rejected as ‘medically and physically unfit for Active Military Service’, apparently because of a chest condition.

The family moved to Renmark in South Australia and went into partnership with Clare’s uncle, Jim McGarvie, in a property called ‘The Hermitage’. Before her marriage Clare had lived with Uncle Jim, after she had been teaching in Tasmania. Jim was friendly with the Cutlack family who had an orange grove called ‘Lancing’ and Clare became friendly with Joan and Nancy Cutlack. This began a connection between the families, which culminated in Arthur and Clare’s son, Rod, marrying Lucy Basey, Nancy's daughter . Clare gave Nancy a shower tea when she and Alan Basey were married in 1925. Subsequently the Cutlacks moved to Adelaide and Arthur and Clare bought ‘Lancing’ from them. Son Rod has a receipt for a £100 down payment on ‘Lancing’ dated 1925.

Times were hard and no matter how good the orchardists were at growing the fruit it was difficult making a living out of fruit growing. Many of the fruit growers walked off their land, including the Baseys who went to Adelaide where Lucy was born in 1928. In the meantime Jim McGarvie heard of an opportunity for farming in Western Australia and went there to investigate. On 30 April 1928 he sent Arthur and Clare an enthusiastic reply paid telegram. I have added punctuation for ease of reading.

“I have inspected property thirteen hundred acres, good house, five rooms, water laid on, near school, good railway. Town Wongan Hills line 130 miles from Perth. Price 5700 pounds giving in Tractor, Harvester, Drill Disc Cultivator, and two thirds share in 250 acres of wheat. We will have no work to do until after harvest. They will take over my mortgage and three hundred pounds cash. Balance can remain five years 7 per cent. I am satisfied good. What do you think? Reply at once McGarvie, Gordon's Hotel, Murray St, Perth.”

The place was ‘Wenscote Barton’ via Wongan Hills, and the family’s move there coincided with the start of the Depression. The nearest town was Ballidu. It turned out the farm was useless because of a poisonous weed growing on the property. They could not even graze cows because of the weed, so had goats. Ian and Pixie used to milk the goats and the family had goat’s milk, goat’s butter and goat’s cheese. The goats wore a yoke to stop them getting through the fence into the wheat. Rod, who was a toddler at the time, insisted on having his own yoke and would wander around all day with his yoke on.

Lucy recalls the difficult years of the Depression in the 1930s when, as a small child, she attended a one-teacher school with children whose families lived out in the scrub in tents or humpies made out of corrugated iron. The only children who came to school with shoes were

page 110

the ones whose fathers had jobs. Her father worked as an accountant/manager of the Woorinen packing shed so Lucy’s family had a house.

Section of the telegram sent to Arthur and Clare by Jim McGarvie >

Arthur, Ian and Jim McGarvie tried harvesting and distilling eucalyptus oil. This they did successfully but they could not get into the European market. They wrote to Frank McDougall (a family friend married to Joyce Cutlack) who was an Economic Councillor to the Australian High Commission in London. Rod has letters in which 'Mac’ explains the lack of commercial viability for the product because of an oversupply in Europe.

Clare, Ian, Pixie and Rod moved to Perth so the two older ones could go to school. They lived in a rooming house where they had the use of the front room, a verandah and a shared kitchen at the end of a long hallway. Half the time there was no money to buy food and Rod tells us the story of Pixie preparing an evening meal with three pots on the stove, then walking up the hall with the steaming pots, past the other boarders, sweeping into the front room and carefully closing the door behind her. Two of the pots contained nothing but boiling water, the third contained three slices of bread covered with cocoa made with water.

A neighbour called Ralph Currie made tomato sauce. He had a T-model Ford truck and he and Clare drove around trying to sell the eucalyptus oil and the tomato sauce. Stopping on a hill in one town they put a stone under the wheel to stop the truck rolling backwards. However the load on the back was too heavy and the truck tipped up with its front wheels in the air and all the bottles of oil and tomato sauce tipped out. That was the end of that venture.

Pixie remembers staying in Perth with ‘Uncle’ Jim (James Need Robertson), his wife Chris and their three children, “The older girl [Adie] was engaged to a farmer and Molly was a teenager”. On another occasion the family stayed in accommodation run by the Women’s Temperance Union. Nan Robertson was working for the WTU in WA at the time. Whether these visits were before, during or after their time at Wongan Hills is not clear.

Clare sold all her jewellery and her beautiful riding clothes and Arthur his tools, but despite the hardship Rod and Pixie say they never felt deprived. The children knew they had to be educated, ‘that was in the family, part of the Scottish thing’. There are some tales about their early education in the sections about Pixie and Rod’s lives.

After the failure of the farming ventures, Ian went to Carnarvon as a jackeroo. Sid Dickins, the husband of Arthur’s sister Lottie, offered Arthur a job in their grocery business, so they managed to buy Arthur some decent clothes and he went back to Victoria. Clare, and the children eventually joined him and they lived in Kerr Crescent, Camberwell. Arthur drove trucks for SE Dickins and supervised some of the stores but resigned in support of his sister at the time of Sid and Lottie’s divorce.

Arthur died of throat cancer in 1948. As his death approached, Arthur worried that he had never been baptised. His brother George was serving at the Presbyterian Church in Malvern, so the family rang him and he came over within half an hour and baptised Arthur. The family was impressed by how gentle and patient George was with his brother.

Except for two periods working as a governess on properties in NSW and SA, Clare lived the rest of her life in Melbourne. When her grandchildren came along she spent one day a week with them. Rod tells us that his mother was an “indifferent cook but a real home maker. She had a keen eye for good furniture much of which she acquired at Young’s Auctions in Camberwell, where she became known as ‘the lady in the Astrakhan cap’. She was an inveterate arranger of furniture and one learnt to be observant about this in order to avoid sitting down on a chair or bed which wasn’t there. She loved flowers and the house was graced by her beautiful floral

page 111

arrangements, which she spent so much time on, she was still in her dressing gown when guests arrived. We remember her saying often, ‘Let’s make plans’, which could mean designing houses with the inevitable complication of middle rooms with no windows, or simply indulge in flights of fancy. For she was always a dreamer - and a very charming one at that!”14 Clare died of heart failure in 1965.

Margaret ROBERTSON (1885-1950)

Fifth child and second daughter of Robert Robertson and Mary Jane Cairns, born at Port Campbell in 1885. Known as Maggie.

Maggie and Lottie Robertson on the steps of Barwon Bank, circa 1908 >

Maggie was a teacher at Geelong Grammar School from 1914 until February 1931. She had Primary Registration. Michael Collins Persse, Curator at Geelong Grammar School in May 1999, supplied the following information:

“Miss Robertson taught the little boys in Junior House during the first years of the school at Corio (after it moved from Geelong). She lived at the school in a house in Biddlecombe Avenue, and ate with the Matrons, being the only woman on the teaching staff. I have always heard nice things (eg. from Sir James Darling, Headmaster 1930-1961) about “Robbo” as she was affectionately known.”

The school magazine, ‘The Corian’, of May 1931 paid the following tribute to Margaret, under ‘school notes’ on page 8:

“We were very sorry when early in the term Miss Robertson left us. For a great many years, as mistress of the first form, she has directed our youthful minds on to paths of wisdom and if some of us have not gone very far it was not for want of a good beginning. When she left, the Senior Prefect presented her with a cutlery set on behalf of those who, remembering how good she was to them, could also appreciate the amount she had done for them.”

And under ‘Junior House’ on page 77:

“We are very sorry indeed to say good-bye to Miss Robertson, who has been with us for so long. Her work in the junior form and her helpfulness in so many directions will cause her departure to be greatly felt. She was presented at an assembly of the School with a case of cutlery from her many friends. Her influence has been felt throughout the School, and she carries with her our sincere good wishes.”

The thing most people seem to remember and comment on about Margaret are the airs and graces she assumed. She dressed stylishly and often wore a long string of pearls. Marjorie Mathieson tells us these were left to her by a theatrical friend along with much of the friend’s elegant clothing.15 Auntie Margaret sometimes looked after the older Dickins children when Lottie was busy with another confinement and the children do not have happy memories of her school ma'am discipline. There was not normally any limit on the amount of milk the children drank, but Marie recalls that Auntie Margaret dealt out a set quantity of milk for each child each day and they were not allowed to have any extra. Neil remembers her sleeping during the day when she was supposed to be minding the children and his mother having to get up to attend to them. Other nieces and nephews have happier memories of Margaret and remember her with great affection.

Maggie Robertson >

Maggie Robertson >

She is holding her niece Barbara Dickins who was born in March 1933.

Margaret never married. A budding romance with her cousin Arthur McCue has been mentioned, but the family firmly put a stop to this. There is also the suggestion she had a beau or may have been engaged to a man who was killed during the First World War. I have three postcards sent to Margaret from two different soldiers during the war. The first two are continuous with a final card or cards, along with a signature, missing. The writer mentions his experiences travelling through Egypt, France and England (the train, the scenery, the boats etc). Margaret is addressed as ‘Dear Maggie', so I wonder if these cards are from one of her brothers or some other relation. The third card is from a Frank Hennessay who addresses her as ‘Dear Miss Robertson’ - "Hope you are persevering with the cello. I am looking forward to hearing you on my return”.

Margaret requested that after her death and cremation, her ashes should be sprinkled over Corio Bay. Sid Dickins hired a small plane to carry out this task.

William Henry Gladstone ROBERTSON (1888-1917)

Sixth child and fifth son of Robert Robertson and Mary Jane Cairns, born on 1 July 1888, at Port Campbell. Known as Glady.

Glady and his older brother Arthur were great mates. There are stories about the two of them in the section on Arthur, and it seems Glady was not much interested in getting an education.

In his army records, of which I have a copy, Glady is described as five foot seven and a half inches tall and weighing 145 pounds, with dark complexion, grey eyes and brown hair. His occupation is recorded as ‘drainer’.

Glady married Alice HARLOCK (1886-1957) the daughter of William Harlock and Sarah Dillon of Pomborneit, at Pomborneit in 1913. They had two sons, Rad (1914) and Locky (1915), both born in Geelong. On his recruitment paper Glady gives his wife’s address as Newtown, Geelong. This was later changed to Barwon House, so Alice must have moved in with her parents-in-law at some stage during the war.

Glady joined the AIF on 17 January 1916. He served in France and rose to the rank of Sergeant in the 60th Infantry Battalion. On 27 September 1917, Glady was wounded in action at Ypres.

He died at the 11th USA General Hospital, Camiers on 3 October 1917, and is buried in the Etaples Military Cemetery.

page 113

William Henry Gladstone (Glady) Robertson >

Taken in 1916 before his departure for France.

A letter to Robert Robertson dated 18 January 1918 and signed by General W H Birdwood, relates that on the morning of 26 September Glady took part in an attack on Polygon Wood east of Ypres:

"... During the same evening, when your boy’s company was in the support trenches, the enemy put down a heavy artillery barrage, preparatory to, and during their counter attack on the front line, causing considerable damage to our trenches.

It was particularly at this stage that your boy distinguished himself. Throughout the bombardment he moved about freely, regardless of all personal risk, and his courage and coolness under very trying conditions were invaluable in setting a fine example to his men. He rendered splendid service in reorganizing the company, when the enemy attacked and failed, and displayed great initiative in leading his men forward to meet the enemy.

It was while doing this, that to my great regret he was wounded. His commanding officer informs me that he was very shocked to receive the news, that his wounds proved fatal, for though he appeared to be badly shaken, he was as cheery when going down to the ambulance station, that those who saw him were deceived as to the seriousness of his condition.

Those who were with him cannot speak too highly of the fine soldierly qualities he displayed during the critical time I have mentioned, and I was so glad to have the opportunity of awarding him the Military Medal which he so thoroughly deserved for his good and gallant work.”16

There are two letters written to Alice, one is from Rose Butler, the nursing sister who was with Glady when he died and this reveals that he had a serious shoulder wound. The other is from Private Howard Iredale who served in ‘Robbie’s’ platoon. Both letters speak of the writers’ admiration for Glady and mention the photos he carried of his wife and children. They make sad reading.

Another two letters, reveal that the Military Medal sent to Alice was only inscribed with the initials W T Robertson. The medal was sent back so it could be re-inscribed with the G for Gladstone included. The letter Alice wrote is dated June 1918, and gives her address as 15 Volum St, Manifold Heights, Geelong.

I know very little about Alice’s life from this time on. One of her grand daughters tells us that Alice did not have an easy life with two small boys to raise. “I remember her telling me that the only way to separate them when they fought was to turn the hose on them. Her hair was white by the time she was thirty - Lock called her Snow. She was a gentle loving grandmother to me - in fact a second mother when my parents separated. I remember her with much love and affection.”17

page 114

In later life Alice lived in Cotham Rd, Kew not far from Lottie Dickins and she was one of the relations Lottie kept in touch with. I remember her as a tall upright woman with a gentle manner, wearing the matronly clothes that all middle aged women wore at that time.

Alice died at the Repatriation Hospital, Heidelberg, on 31 July 1957. She requested that her ashes should be scattered on her husband’s grave in France and her son Rad arranged for this to be done.

George Gordon ROBERTSON (1890-1954)

Seventh child and fifth son of Robert Robertson and Mary Jane Cairns, born at Geelong on 11 November 1890.

George worked for a time as either an engineer or an engineering draughtsman. According to his nephew Stuart Robertson, his architectural drawings of a bridge built over the Barwon River between Geelong and Belmont, hung in a frame on the wall at Barwon House. Another project George worked on was the design of the Hume Weir. George was also involved in building a bridge at Renmark, SA. The bridge collapsed and it was after this event that George decided to train for the Ministry.18 This is not meant to infer that George was in any way responsible for the collapse of the bridge, just that it appears to have been a turning point in George’s life.

George Robertson at 14, with his brother Stuart and his sister Lottie >

George’s time in Renmark must have coincided with his brother Arthur’s fruit growing venture, for there is an undated paper cutting, presumably from the local paper, lauding the brother’s singing of duets and individual solos, at a fund raising concert for ‘Mr Gibbon’s candidature in the Ugly Man Competition’.19 George was an accomplished pianist as well as a singer with a fine tenor voice.

George’s daughter Ailsa tells of the difficulties George had to overcome so he could train as a Presbyterian Minister. These included, “How to finance the procedure and pre-requisites in education such as two years study in Classical Greek prior to acceptance. I am not sure at what stage he entered Ormond College but he graduated in 1929 after six years study. During this time he spent two years in the Mallee at Ultima, where he batched with a Doctor in a shared house. ... [He told] of the hardships of the farmers in trying conditions of droughts and dust storms.

He and the doctor made a wooden coffin for a new born baby who had not survived birth.”20

In about 1922 George served as a home missionary at the State Electricity Commission’s men’s working camp in Yallourn. His daughter writes, “They were very rough times - dealing with men from all walks of life - reformed or not criminals (Squizzey Taylor often paid a visit) alcoholics and gamblers who handed over to him the major portion of their pay packets before a weekend of drinking and gambling.” George made friendships here that lasted for the rest of his life.

page 115

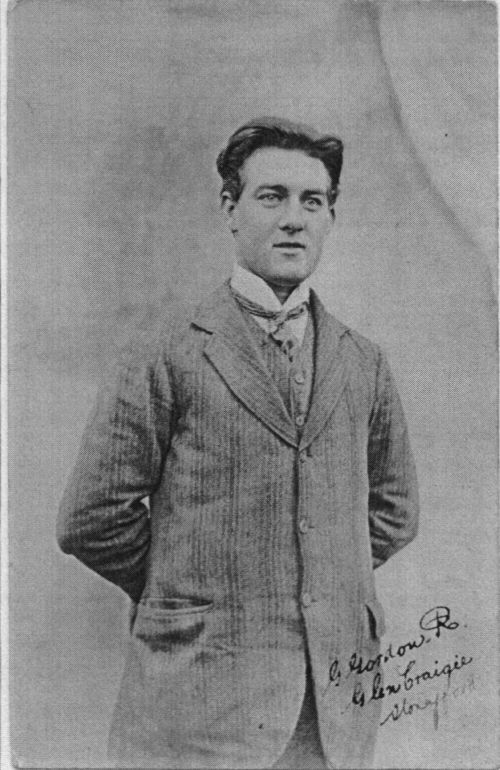

George Gordon Robertson >

A postcard was sent to Lottie with birthday wishes in June 1912.

In February 1930 George married Evelyn WADMORE (1893-1979). The two had known each other through the church in Geelong and George had sung at the funeral of Evie’s sister who had died from meningitis at the age of sixteen. “They lost touch but renewed friendships when they met on the train to Albury - she going to see her brother Will who had just been made manager of the Commonwealth Bank and he to work on the Hume weir. He offered to carry her case!” Marriage had to be put off until George had finished studying for the Ministry.

George’s ‘exit charge’ was the Presbyterian Church at Tylden in Victoria. Robert and Molly attended their son’s induction at Tylden, as did brother Rab and his wife Fanny.21 Rab was the Baptist minister at nearby Kyneton and the two families would visit each other. “A great friendship was built up between the two brothers and their wives.” George and Evie’s only child, Ailsa, was born at Kyneton in 1931. Evelyn was very sick after the birth and George’s sister Nan stayed with the family for at least a month to help out.

In 1933 the family moved to Traralgon where they “spent six happy years”. In 1939 George accepted a call to the Presbyterian Church in Bourke Rd, East Malvern. The move to Melbourne meant that Ailsa could attend the Presbyterian Ladies College.

Apart from his parish work George's special interest was as Convener of Chaplains for the Gaols and Hospitals. He was also a member of the Presbyterian Board of Education. “He was always in attendance at the Presbyterian Assembly held at the Assembly Hall in Collins St, where he met and mingled with as many colleagues as was possible.” Ailsa remembers coming from PLC East Melbourne on the Collins St tram to meeting him at the Thistle Tea Rooms’ next to the Assembly and being introduced “to all these wonderful people.”

George was forced to retire at the age of fifty-eight because of ill health. The family continued to live in Malvern. George “was clever with his hands and had many hobbies.” These included music, gardening (specializing in tulips, gladioli and dahlias) and making furniture from wood brought from the Gippsland forests. Ailsa and George enjoyed singing duets, “Ailsa playing his accompaniments as he and Arthur may have done years before.”

George died in 1954, Evelyn died in 1979. Ailsa pays the following tribute to her father: “He was a gentleman with a kind loving patient nature, who was inspired by the highest of moral principles for the betterment of mankind and with all this was the friend of everybody”.

page 116

Charlotte Spurgeon ROBERTSON (1893-1976) - married name DICKINS

Third daughter and second youngest of Robert Robertson and Mary Jane Cairns’ nine children born at Geelong on 30 June 1893. She was named after the Baptist theologian Charles Haddon Spurgeon (1834-1892) and Lottie considered she was lucky not to have had the Haddon put onto her name as well.

Third daughter and second youngest of Robert Robertson and Mary Jane Cairns’ nine children born at Geelong on 30 June 1893. She was named after the Baptist theologian Charles Haddon Spurgeon (1834-1892) and Lottie considered she was lucky not to have had the Haddon put onto her name as well.

< Stuart and Lottie Robertson

Lottie gave the impression that her childhood was not particularly happy. By the time she was growing up, Robert had become an established evangelist and he was often away from home for long periods. During his absences Molly had to manage with her large family as best she could. Lottie was expected to be responsible for her younger epileptic brother Stuart and resented this. At the age of about nine she was sent to stay with her cousin Barbara Crouch at Woomelang in the Mallee, for two years. The reason given was that she had a weak chest and needed a dry climate.

Despite her intelligence Lottie’s schooling was limited and she left school at fourteen. She made up for this in later life by being a voracious reader of all kinds of books. When she was a semi invalid in her older years, her children would be sent up to the Kew Library to renew her books and it was always hard to find something she had not yet read. With her own children Lottie insisted they receive not only a good education, but were all trained for occupations with which to support themselves.

Lottie Robertson in her twenties >

After leaving school Lottie stayed at home and was expected to help her mother look after Stuart. Later she went to live with her Uncle Arthur Robertson at Port Campbell, to help care for her grandmother, the aging Margaret Rutherford Cairns Robertson. Lottie got on well with Grandma Rutherford, as she always called her, and felt closer to her than to her own mother. She told many stories about Grandma Rutherford and the handsome Geordie Cairns, who had been her grandmother’s first husband. She also told of Arthur coming home drunk and her being terrified he would set the house on fire as he reeled about carrying a candle. This gave Lottie a life long terror of house fires.

Lottie commenced studying at Art School in Geelong but her parents objected to her mixing with the male architecture students, and when she brought home a still life she had painted, of a cigar, cigar box and a beer bottle, her training as an artist was brought to an abrupt end.

A young man who was an atheist courted her. He had no objection to her religious participation and would walk her to church on a Sunday, wait for the service to be conducted, and then walk her home. Again parental disapproval interfered and the romance was ended.

page 117

In 1916 Lottie married Sidney DICKINS (1892-1964). Sid was the fifth child of Thomas Dickins and Henrietta Peake. Thomas Dickins’ family had a foundry and ironmongery business in Geelong. Sid and Lottie attended the same school, although they were one year apart in age. We know they were friendly as early as 1910, for there is an entry by Sid in Lottie’s autograph book, dated that year. Their marriage took place at Barwon House with Lottie’s brother Rab conducting the service. There are two photos of the wedding party, both family group photos with the bride’s parents as the central characters, rather than the bride and groom. These photos are reproduced at the beginning and end of this chapter. There were no photos of the bride and groom alone or with their attendants, as this, according to Lottie, was considered a form of vanity! Lottie wears a simple white suit.

Charlotte Spurgeon Robertson >

At the time of the marriage Sid was working in Sydney for the grocery firm of Moran and Cato, so the young couple moved there to live. It seems however the marriage was in trouble right from the start, as Lottie left Sid and came back home. Her father persuaded her to return to the marriage. Their first child arrived in 1923, with six others following. The last baby was stillborn towards the end of the 1930s. Of the surviving children, Mac (1923), Joy (1925), Neil (1927), Marie (1928) and Barbara (1931), were born when the family lived at King St, Geelong (now called Isabella St). Margaret (1934) was born at North Shore, Geelong.

On their return to Victoria, Sid and Lottie set up their own grocery business, starting off with the first shop in Geelong in 1920. Lottie told of making deliveries of groceries in a horse and cart, on Christmas Eve. The family’s own groceries largely consisted of rejects from the shops, such as bacon ends, broken biscuits and other damaged goods. As children we attended, and enjoyed, picnics, sporting matches and concerts run for and by Dickins store employees.

Sid was an astute businessman. One of his employees, an accountant, told me, ‘I never knew your father to throw away a piece of string’. In 1928 Sid and Lottie opened the first self-service store in Victoria, an innovative idea that caused conflict with the trade unions. During the Depression, bankruptcy was avoided by putting all the assets in Lottie’s name and the debts in Sid’s name. The creditors allowed Sid to continue trading and eventually he repaid all the money he owed. In appreciation his grateful creditors presented Sid with a Grandfather clock, and this is now in the custody of Richard Dickins. The firm of S E Dickins Pty Ltd merged with G J Coles & Co Ltd in 1958. By that time there were sixty-three Dickins self-service grocery stores around Victoria.

As well as helping in the early days of the business, Lottie was always involved in charitable activities and helping others. She would take in boys who had been kicked out of home and Sid would find them jobs in the business. Some of these men worked for S E Dickins all their lives. In 1937 when the business was again prospering, the family moved from Geelong to Melbourne. The big house at 281 Barker’s Rd, Kew, with its tennis court and large garden, was always full

page 118

of people. People of many races and from a whole variety of backgrounds. At one stage Lottie provided a halfway house for people exiting the Kew mental hospital (where Lottie served on the auxiliary). During World War II she provided a home to some Jewish refugees, and scores of servicemen and women, foreign and Australian, came to the house for ‘rest and relaxation’. There was always lots of debate and discussion, musical afternoons, book society meetings, dances, tennis parties, social activities and people staying over. Politics, religion, social welfare, history, films, plays and books, were all topics for discussion, and activities the family were encouraged to participate in.

A strong feminist, Lottie supported women’s causes, using a female doctor for her confinements, and a female solicitor. Despite being a member of the Liberal Party in Bob Menzies electorate, it was fairly obvious that if a woman was standing, Lottie voted for the woman, no matter what party she belonged to. At home, tasks were allotted according to age, ability and skill, rather than sex. The girls were never expected to wait on the boys.

Lottie had a fine contralto voice and had attended singing classes for a short time as a young woman. Throughout her life she sang at social and charitable functions and entertained her children with piano-accompanied monologues. Joy writes, “When we attended church, Mother’s voice would ring out loud and clear, singing in harmony. In my extreme youth I often wished she didn’t have such a loud voice which could be heard all over the church. However as I grew older and learnt to appreciate the quality of her voice, I judged all other singers in relation to hers and most are found wanting.” No matter how hard things were financially (and money was extremely limited after the Sid and Lottie were divorced) money was always found for musical activities - music lessons, musical shows, films and concerts.

Lottie and Sid’s marriage, which had always been shaky, deteriorated further after the stillbirth of their last child. In 1941 Lottie applied for a judicial separation but this was not successful. Then in 1944, Sid applied for and obtained a divorce. The next year Sid married Lottie’s niece, Mary Robertson, the daughter of her brother Rab.

Lottie was a natural mentor and people would come to her with their troubles. She would listen to them, empathize, and if they asked for it, give them advice. Sid visited and continued discussing his business affairs with Lottie, as well as taking an interest in the children, however after the divorce, he never interfered in Lottie’s management of the children. Even when she was bed-ridden in old age, Lottie’s doctor often made her the last visit of the day so that he could sit on the end of her bed and tell her about his growing family.

< Lottie in her older years

Like so many of her kinswomen, Lottie always had handicraft projects in progress.

Lottie was a great one for short pithy sayings, little packages of wisdom, and standard instructions her children could anticipate before they were even uttered. Some became family jokes, others were dreaded, and those of us who have children of our own find ourselves using the same sayings our mother used. Things such as the terrible threat of, ‘I’ll see your nose above your chin’, [took me years to work out that that is where my nose is anyway], or ‘Fools and children should not see things half done’. There are far too many of these sayings to record here.

Perhaps the saddest thing about Lottie’s life was the separation from sections of the Robertson family caused by Sid’s marriage to her brother’s daughter. She could not forgive the disloyalty of some of her siblings, and after the divorce Lottie and her children had little to do with the Dickins family and some sections of the Robertson family.

Lottie had her first heart attack at the age of forty-nine, around the time of the divorce. I was eavesdropping and overheard the doctor tell her in an admiring manner, ‘You stupid woman, you should be dead, but you are not going to die are you’. I felt very proud of her, for I knew she was determined to stay alive and look after us kids. As per the treatment of the day Lottie was ordered complete bed rest, but refused to go to hospital. A district nurse came in regularly and a series of women came in to do the weekly wash. Mac was away at the war and Joy, who was eighteen, took over most of the responsibility for organizing the house and the younger children. Jobs were shared out among us. Heart trouble (angina) plagued Lottie on and off,

page 119

until her death in 1976. She was cremated and her ashes placed near those of her daughter Barbara, at the Springvale crematorium. Recently her ashes were retrieved and her children are planning to re-inter them in the Robertson family grave at Port Campbell.

Stuart Rutherford ROBERTSON (1898-1964)

Stuart Rutherford ROBERTSON (1898-1964)

Youngest child of Robert Robertson and Mary Jane Cairns, born at Geelong on 27 May 1898.

Stuart was epileptic. If he had been born a couple of generations later, Stuart’s epilepsy would have probably been controlled by medication and he could have lived a normal life. As it was, he spent his life being treated as an invalid. He lived with his parents until they died, then shared the family home at Belmont with his sister Nan until she died in 1958.

Stuart’s nephew, also called Stuart (Rab’s son), relates experiencing one of Stuart’s grand mal attacks when Stuart junior was about four years old. The two had been to an art show at the Geelong Town Hall. On leaving Stuart fell down on the footpath in a convulsion and the younger Stuart did not know what to do. Fortunately some passers-by came to the rescue.22

Lottie tells of having to be responsible for her younger brother when they were children. A delightful tale comes from Margaret Haine of Stuart responding to some action of Lottie’s by saying, ‘Remember Lottie, God gave me teeth and nails. They are sharp and I can use them’.23

Nan and Stuart smelling the roses at Peary St, Belmont, Geelong in the 1950s >

I have been told that when Nan died Stuart exclaimed ‘I’m free, I’m free. All this is mine.’ This suggests some resentment about the life he had been forced to live and the controlling influence of his family. Apparently however, Stuart was not specifically mentioned in Nan’s will, which was a sad lack of acknowledgment of the long period they had lived together and shared each others lives. Pixie Robertson believes the family effects were shared out amongst the family or disposed of by Josh and Rab’s daughter, Mary.24 Stuart’s life ended six years later in the Mont Park Home for the Aged.

page 120

Robert Robertson Extended Family

Taken at Barwon House at the time of Lottie Robertson’s wedding to Sid Dickins on 4 January 1916.

Left to right, back row: Arthur, Sid Dickins, George, Fanny (wife of Rab), Josh and wife Josephine, Stuart, Glady. Seated: Maggie, Clare (wife of Arthur) holding son Ian, Lottie, Rab, Robert, Molly, Nan, Alice (wife of Glady) holding son Locky, Arthur (brother of Robert).

Front: Rutherford (son of Josh), Stuart (son of Rab), Rad (son of Glady), Mary (daughter of Rab)

1 Interview with Margaret Haine, July 2002

2 Interview with Stuart Robertson, March 2000

3 Interview with Richard Dickins, March 2000

4 Interview with Stuart Robertson, March 2000

5 Interview with Margaret Haine. November 2000

6 Interview with Richard Dickins, March 2000

7 His birth year was thought to be 1881 but the Victorian records give it as 1880, file number 10848.

8 Information about Josh comes from his son Rutherford and Baptists in Victoria - Our First Century’, as well as other family members mentioned.

9 Interview with R.N Robertson, March, 2000

10 Paper cutting, unidentified newspaper, 2.5.1937

11 Interview with Richard Dickins, March 2000

12 The following is compiled from information and documents supplied by Arthur’s children, Pixie and Rod Robertson, and Rod’s wife Lucy, with incidental information from other family members.

13 Interview with Rutherford Robertson, March 2000

14 Letter form Rod Robertson, 25.10.2002

15 Interview with M. Mathieson, March 2000

16 I understand the original letter, and the ones from Butler and Iredale, are in the custody of Glady’s grandson Bill Robertson, along with the citation for the Military Medal.

17 Letter from Bobbie Chapman, June 2001

18 Interview with Stuart Robertson, March 2000

19 The paper cutting was provided by R and L Robertson

20 This and the following quotations are taken from a letter from Ailsa McLennan, June(?) 2001

21 The Kyneton Guardian, 28.3.1931

22 Interview with Stuart Robertson, March 2000

23 Interview with Margaret Haine, November 2000

24 Interview with Pixie Robertson, March 2000

Garry Gillard | New: 22 March, 2019 | Now: 5 September, 2022