sAnyone visiting Shetland is immediately struck by the stone fences stretching for kilometres across the landscape, and the beautiful use of stone in buildings.

sAnyone visiting Shetland is immediately struck by the stone fences stretching for kilometres across the landscape, and the beautiful use of stone in buildings.

The Folk from the Wind Wound Isle > Chapter 27 : Occupations, Arts and Crafts

page 205

Living in a subsistence economy, Shetland crofters not only had to supply themselves with food, through agriculture and fishing, they also had to provide their own shelter and clothing. Shetlanders were practical people. They had to be to survive in their harsh environment where raw materials were limited.

sAnyone visiting Shetland is immediately struck by the stone fences stretching for kilometres across the landscape, and the beautiful use of stone in buildings.

sAnyone visiting Shetland is immediately struck by the stone fences stretching for kilometres across the landscape, and the beautiful use of stone in buildings.

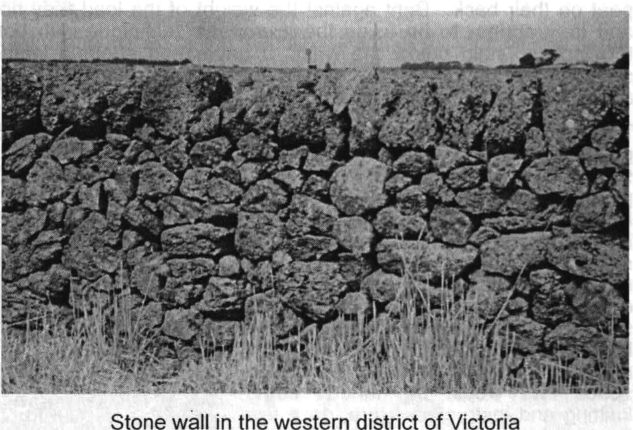

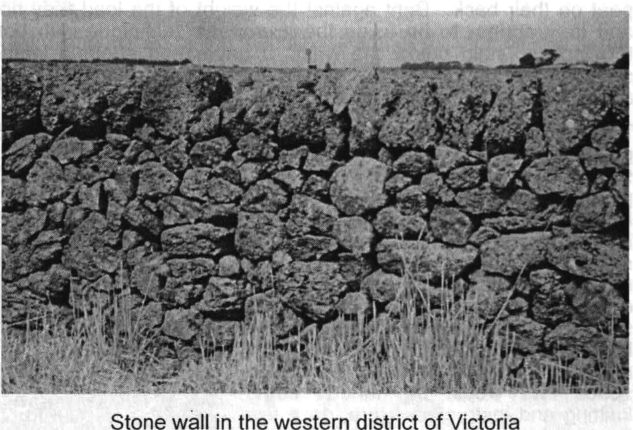

Arriving in Australia the Robertson men used their skills as stone masons to earn a living, participating in the erection of dry stone walls and buildings. Many of these are still standing in the Western District of Victoria.1 Womenfolk went along as cooks, and children were expected to help. Childhood as we know it today had not yet been invented.

Like other settlers, the Robertsons built their own homes from whatever materials were available to them and after taking up ‘selections’, land had to be cleared and crops planted as quickly as possible. Until the farms became established or during times of hardship, such as the depression years of the 1890s, men frequently worked away from home, leaving the women to tend the children and look after the farms, just as women in Shetland had done.

When gathering information for the chart of Robertson descendants I asked people to include occupations. It is interesting to see how many have made, and still make, their living from hands-on occupations such as farming, mechanics, carpentry, dressmaking and handicraft activities. The alternative lines of occupation are more academic and/or service related - church ministry, teaching, nursing and science. Very few of our relations have gone into commerce.

In the early days, employment outside the home for women was limited to domestic work, but taking in boarders was another way of supplementing their income. Quite early on some of the Robertson women became teachers, either in schools or as teachers of music.

My personal interest in handicrafts has prompted me to take note of the handicraft skills that have come down through the women in the family. Both Agnes and Margaret Robertson are listed as 'knitters’ on the manifest of the ship, which brought them to Australia in 1867. Shetland wool and Shetland knitting is famous, and there was an export trade in knitted goods as early as the sixteenth century. In the seventeenth century “there developed a considerable trade with Dutch herring fishermen, and before their arrival at Lerwick each summer large quantities of stockings, gloves and nightcaps were made ready.”2

Although the women did most of the knitting, men also knitted, and knitting became an important source of additional income for the crofters, with the articles they produced being sold or used for barter. Everything that would cover a person from top to toe was knitted, including warm undergarments. Knitters on the island of Unst produced shawls of “gauze like delicacy - so light that a full-size article weighed two ounces [approx. 57 grams]”.3 Another book describes shawls made from hand spun woollen thread as fine as a hair. These shawls took anything up to a year to make. “The fineness of this work enables even large shawls to be pulled through a wedding ring.”4

Somewhere I have read that when drowned seamen were washed up on the shore, the place they came from could be identified by the pattern of the knitted garments they were wearing. These days the traditional patterns from Fair Isle, Fetlar, Yell and other parts of Shetland are copied, imitated and mass produced all over the world. However knitting is still an important industry in Shetland, although much of the work is now done by machine. When I was in Lerwick in May 1997, I went into a shop, which was stacked from floor to ceiling with knitted articles. 'My goodness,’ I asked, ‘will you sell all these?’ ‘They will all be gone by the end of the summer.’ replied the salesperson, ‘We knit all winter and sell it in the summer.’

There are wonderful old photos of Shetland women knitting as they carry kishies (baskets) of peat on their back. Bent against the weight of the load they hold their needles at waist level and they appear to be using the ’European’ technique with both needles (wires in Shetland terminology) held below the wrist. I have read about a leather knitting pouch, which was strapped around the waist and used to hold the needles in position, but so far I have not been able to find a description of just how this functioned.

Shawl made by Nan Robertson circa 1950. >

This same underhand knitting method may have been used by Molly Cairns Robertson, for her granddaughter Mary wondered how she could ‘see’ what she was doing as she knitted patterned socks, the wool tucked into her belt and the needles held beneath her ample bosom.5 Several people have spoken of Margaret Henderson knitting a pair of socks in a day - one before lunch and the second sock during the afternoon. My mother Lottie was a great knitter and did beautiful crochet work, and her sister Nan supplemented her income by selling her handiwork. If Mum found my sisters or me sitting about ‘gazing into space’, we would be handed some knitting and instructed, ‘Here, do a few lines of this while you are sitting there.’

Time must not be wasted!

Like music the theme of handicrafts comes through in the stories I am told about Robertson female descendants and in the potted biographies you will find reference to the handcraft skills of individuals. Adie Robertson Reudavey was a judge of handicrafts for the Royal Perth Show and the rural show circuit in Western Australia. Her sister Mollie (Mary Linda Gillard) was a professional dressmaker, designer and tailor. Other members of the family have turned their skills to woodworking or the fine arts, becoming painters and artists.

1 J. Black, 'If These Walls Could Talk', provides detailed information about the construction and location of dry stone walls in the Corangamite areas of Victoria's Western District.

2 J.R. Nicolson, 'Traditional Life in Shetland', p.99

3 J.R. Nicolson, 'Traditional Life in Shetland', p.99

4 M. Smith and C. Bunyan, 'A Shetland Knitter’s Notebook’

5 Interview with Mary's son, Richard Dickins, April 2000

Garry Gillard | New: 28 March, 2019 | Now: 5 September, 2022