The Folk from the Wind Wound Isle > the Robertsons in Shetland

page 9

How was it this family of Robertsons came to Australia? Who were they and what do we know about their origins? Why did they leave Shetland?

page 9

page 10

Robertson means son of Robert, and it is a common name in Shetland as well as in mainland Scotland. There is not necessarily any connection between Shetland and Scots Robertsons, although there is a tradition in our family that our Robertson line moved to Shetland from Scotland at some time unknown, because of religious persecution. I have no concrete evidence to support this. Indeed it would seem the Shetland line of our heritage is more Norse than Scots, and Marjorie Mathieson told me that her great grandfather Arthur Robertson, the first one to come to Australia, was often heard to say, ‘Achl The dirty Scot, we’re Norse’ - suggesting he saw himself as having Scandinavian rather than Scottish affiliation. Both Manson and Henderson are Norse names, Manson being a derivative of Magnus, and Agnes Williamson, according to Robert Robertson, was of Swedish extraction.

The standardization of surnames did not become common practice in Shetland until late in the 18th century. Prior to this the use of patronymics by the locals means it can be hard to trace lineage. We not only have the use of the suffix son, as in Robertson — son of Robert, and Henderson - son of Henry, but names such as Thomasdaughter — daughter of Thomas. William the son of Robert would be known as William Robertson but if William had a son called Thomas, he would be known as Thomas Williamson and so on. Women continued to use their own name after marriage and this is how they appear in the records until late in the 19th century. Following this custom, I always refer to Arthur Robertson's wife as Margaret Henderson.

While I was in Shetland, I was told that the traditional practice in naming children was to call the first son after the paternal grandfather and the second son after the maternal grandfather. The first daughter was named after the maternal grandmother and the second daughter after the paternal grandmother. The naming of later children was less regulated. This rule for naming children was not always applied, but it can give a clue to family connections and lineage.

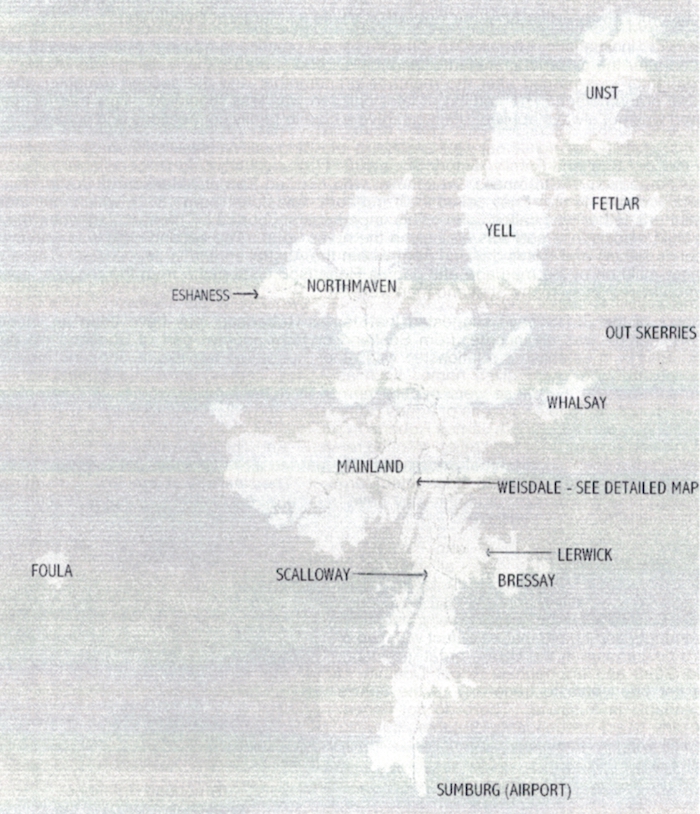

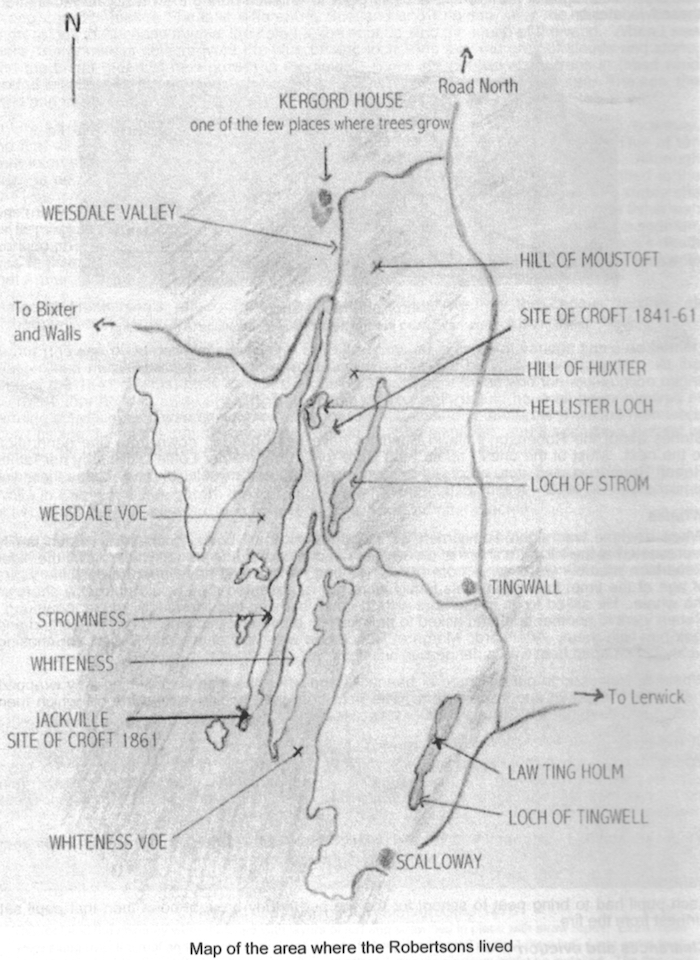

The first definite record of our Robertsons in the Tingwall/Weisdale/Whiteness and Hellister area that the Shetland Family History Society (SFHS) and I have so far been able to locate, is James Robertson of Stromness, Whiteness, who married Barbara Manson of Cova, Weisdale on 26 December 1811. 1 They called their first-born child John (born 1812), which may indicate that Arthur’s father was called John. This is perhaps supported by the fact that when the first- born child died, a third son was also given the name John. The second child was Arthur (after Barbara’s father) and this is the one from whom the Australian line is descended. There were no more children of the marriage and James Robertson disappears from the records, possibly drowned at sea as so many Shetland men were.

Members of the SFHS have suggested that James Robertson may have been an ‘incomer’. But whether he was an incomer from Scotland or from another part of Shetland we do not know. Efforts to establish a relationship with other Robertson families in Shetland have been unsuccessful. We share given names such as Agnes, James, John and Robert with other Robertson families, but these were popular names in many families who have different family names. There seem to be dozens ofAgnes Robertsons and one is recorded in the Tingwall area in 1785. Was she related? A James Robertson of Moustoft, with a family of five, is listed in the 1804 Weisdale records for food relief. Was he related? And Thelma Watt of the SFHS has found the record of a John Robertson of Stromness who married a Philadelphia Tait in 1816. They had sons called John and Arthur and a daughter Margaret. The similarity of age, location and names suggests to me that James and John may have been brothers but this cannot be substantiated from the limited records available.

Our Arthur’s younger brother, John Robertson, was a shopkeeper. He lived all his life in Shetland but some of his descendants emigrated to Australia, Canada and the USA. I have quite extensive details about John’s family and their descendants and I have made contact with two of John’s descendant in the USA - great grandson, David Gunn and his nephew Roger Douthitt. I have not been able to trace any of the John’s descendants in Australia. There do not appear to be any direct descendants of either Arthur or John still living in Shetland.

I have not been able to trace any of the John’s descendants in Australia. There do not appear to be any direct descendants of either Arthur or John still living in Shetland.

American relations, Roger Douthitt and David Gunn >

page 11

There are a number of books available which describe the history and traditional life of Shetland much better than l can do and any of you who have visited Shetland, and the museums there, will be aware of the difficult life our ancestors lived. 2 A harsh climate. High rates of child mortality. Menfolk lost at sea. Periods of famine when crops failed. 3 Oppressive lairds/landlords. Bureaucrats and clergy imported from Scotland intent on imposing Scottish ways of doing things. 4 And a political system that supported the landowners against their tenants. Before the 19th century when roads were built, transport in Shetland was by foot or by boat around the coastline. Individuals stayed very much within their own communities and communities were contained within a particular geographical area. Marriage options were generally limited to those living within those areas.

The reading l have done suggests that the inhabitants of Shetland and Orkney, along with the Highlanders of Scotland, were regarded by the English and Lowland Scots as an inferior race who were uncouth, ignorant and incapable of making the best use of the land they farmed. How similar this sounds to the attitude some of our forebears held and some people still hold with regard to the Aborigines who were displaced by white settlement in Australia.

The Highland clearances, when landlords demanded greater returns from their properties and replaced crofters and tenant farmers with sheep, occurred a little later in Shetland than elsewhere throughout the British isles. The main effect was felt in the 1850s and 1860s when hundreds of Shetlanders emigrated to Australia, New Zealand and Canada. There were programs for assisted emigration and Norah Kendall outlines some of these in her book With Naught but Kin Behind Them. Looking through the records of the Tingwall Sheriff Court Processes for the 1850s and 1860s, l was struck by the number of ‘orders for removal’ brought by landlords against their tenants. Some were absentee landlords who lived in the cities of England and Scotland. They seem to have had little sympathy for their tenants and described the clearances as ‘improvements’. An early version of economic rationalism?

The Shetland l found on my visit in May 1997, is of course very different to the Shetland of history books. However the wind blows just as it always has and island activities are still

page 12

very much controlled by the seasons and changing weather patterns. The Norse influence is strong and this makes Shetland different to Scotland and England. For me, the most lasting impressions of Shetland involve the colours, the sounds, and the touch of the wind. When I was there, the dominant colours were the blue of sea, lochs and sky, the grey of clouds and stone, and the bright green of new growth in the fields. There are not too many trees in these wind wound islands and there are few places where you are out of the sight of the sea. The sea, the wind and the seabirds are ever present.

The Wind Wound lsle

Wind ruffles the surface of Weisdale Voe.

The registration of births and deaths did not became obligatory in Scotland until 1855, however the first all-Shetland census was held in 1841 and this was followed by further censuses at ten year intervals. These along with other records tell us something about our forebears. Although there is no record of James Robertson’s death, his wife, Barbara Manson, is described in the 1841 census as ‘widow’. The record of her death in 1866 at the age of eighty-four, states she was the ‘widow of James Robertson farmer’. We can assume that James was also a fisherman as farming and fishing were joint activities for crofters and he may have also been a seaman working on British ships that picked up crew in Orkney and Shetland. Barbara Manson’s death was registered by her grandson Arthur Robertson Jnr who signed with a cross. This suggests that Arthur Jnr may not have been able to write at that time.

Margaret Henderson’s father, Peter Henderson, is described in the census records as ‘fisherman’, as is her brother, Walter Henderson.

Arthur (the son of James Robertson and Barbara Manson) is listed at various times as farmer mason, and music teacher. We know from family stories that he was also a seaman. At the time of the 1841 census, he is recorded as being absent from home and the assumption might be made that he was away at sea. The women of the family would have all been involved in farming activities, as it was the women’s responsibility to maintain the farms while the men were away fishing during the summer months. Women were also knitters, and it seems an interest in knitting and other handicraft has come down through the family in Australia.

Arthur’s brother, John Robertson, is described in the census as merchant, grocer and farmer. While in Shetland I was shown the building where he had his shop at Strombridge. At the time of her death in 1881, his wife Joan is described as ‘widow crofter 2 acres’.

Arthur’s sons, James and John, are recorded in the 1861 census as ‘fishermen’. James was a crew member on whaling ships in 1858 and 1859. Whaling ships went out during the summer months to the seas around Iceland and Greenland. Family stories claim John had his own boat

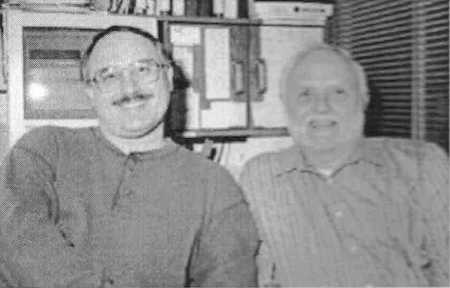

Shetland Croft Museum, Southvoe circa 1870

The roof and the chimney were thatched with layers of turf and straw tied in place with straw ropes. Extra ropes were slung over the roof and weighted with large stones to keep it anchored against the wind. Light came from tiny skylights at eaves level. If and when the croft could afford it proper windows might be installed. The floor was flagstones or packed earth. The dwelling part of the building was divided into two rooms one for living the other for sleeping. The main focus was the hearth where a peat fire for heating and cooking, and for drying fish and meat, burned continuously. Adjacent to the living area, divided from it by a passage, was the byre where feed was stored and a milking cow tethered during the winter. Next to the cottage is the barn with bins for storing bare (barley) and oats and all the farming equipment. There was a hard floor for thrashing, sheep skin platens for sifting and sorting the grain; and a ‘quern’ (a hand turned stone mill) for grinding it. At one end of the barn was the kiln for drying grain; this is the round section slightly detached from the house above.

page 13

was a privateer against the French, and ran guns to America during the Civil War. More about these two later on.

John Robertson's shop, 2000

There have been several additions and alterations to the building.

Stories about the Robertson's life in Shetland have been handed down from one generation to the next. Most of those I relate here were told to my mother Lottie Dickins by her father Robert Robertson, and were recorded by my sister Marie and myself. ln many cases there are similar stories in other sections of the family.

When a whale was sighted, the men would go out in small boats to chase it. Each family represented at the kill got a share of the whale. On one occasion, when a whale ‘blew’, the older Robertson menfolk were away from home. Robert, who would have been about nine years of age at the time, knew that if his family were not represented they would not get a share of the whale. He asked to go in the boat with the men but was told ‘No laddie you're too young’. Robert went to another boat and asked to be taken on board and this time the crew relented and took him with them. Afterwards Margaret Henderson was very angry with Robert, for chasing whales in an open boat was a dangerous business.

Whale oil was used to put on bread or bannocks and when the men went fishing they wrapped their ‘sandwiches’ up and sat on them. The heat from their bodies melted the oil, which then soaked into the bannock. Whale blubber was also used to fuel lamps.

Money could be made by collecting down from birds nests on the cliff faces. Young men or boys were let down on ropes from the top of the cliff. This was another dangerous occupation and men sometimes fell to their death. “The men were either sailors or down collectors and were therefore either drowned, lost at sea, or fell to their death.“

A local superstition said that if you killed a lark you broke a toe; young Robert was a good shot with stones, he killed a lark and sure enough he broke his toe.

Each pupil had to bring peat to school for the fire and if they brought none then that pupil sat furthest from the fire.

Coming home from a trip at sea Arthur Robertson discovered the Laird had fenced off the common land to graze his sheep. This made Arthur so angry he pulled the fence down and knocked the laird down. He was charged with assault and fined. Lottie believed this was the reason the family left Shetland. As my mother told the story, the laird was married to Arthur’s sister and lived in ‘the only two-storey house on the island‘. This is certainly not correct as Arthur did not have a sister and there were many two-storey houses in Shetland at the time. However the laird’s house may have been the only two-storey house at Hellister or Jackville where the Robertsons lived.

Weisdale Valley and Hellister Loch

View from Weisdale Hill on the western side of the voe.

Hellister Loch

Showing the narrow section of land between the loch and the voe seen in the previous photograph. This is the area where the Robertsons had their croft at the time of the 1841 and 1851 census.

John Collins McCue has a variant of the same story, “Coming home from a whaling trip, Arthur Robertson discovered that his brother-in-law, having been sub-let the whole of the ‘hinterland’ by an English landlord, had enclosed the village within a dry stone wall and was charging rent for what had been common grazing. He knocked down then his brother-in-law and was prosecuted and fined." 6

Thelma Watt and I can find only the most tenuous relationship between the Robertsons and Laurence Calder, who was the family’s landlord at Hellister. John Robertson’s wife was Joan Smith and she had a sister called Philadelphia. The father of Philadelphia Smith's illegitimate son Robert, born in 1856, was Robert Calder, the son of Laurence Calder. Philadelphia obtained a court order against Robert Calder for the payment of “three pounds sterling per annum in name of aliment to an illegitimate male child”. This was to be paid until Robert Jnr reached the age of seven but it seems Robert Calder, who is described as a sailor, avoided his responsibility by taking himself elsewhere. Robert Jnr was recorded in the 1861 census as Robert Smith (4 years) but in 1871 he is recorded as Robert S Calder (15 years). 7

These stories demonstrate the unreliability of tales that are handed down from one generation to the next, becoming exaggerated or changed as they go. They do however give us clues to follow up. I was not able to verify the assault charge but it was while trying to locate a record of the assault case in the Tingwall Sheriff Court Processes that I found two eviction orders taken out against Arthur Robertson. If Arthur Robertson did in fact assault someone this may have well precipitated one of the two evictions.

The first eviction, in April 1858, was from the land at Hellister owned by (or sub-let to?) Laurence Calder. Living there at the time of the 1851 census, Arthur is described as "farmer, 4 acres, employs 2 labourers”. 8 After being evicted from Hellister the family moved to Jackville at the tip of Stromness where, according to the 1861 census, the family had 8 acres. Their landlord was Alexander McCrae Bruce of Binnaness. The family was evicted from this site in October 1862.

Crofts were held “in virtue of a verbal lease from year to year" and the order for removal charged the tenant to “flit and remove himself, his family, servants, cottors and dependents, goods and gear, forth and from the house called Jackville Cottage and farm and others held by the Defender.“ Unable to find Arthur Robertson in person, the first eviction notice was issued to his wife, Margaret Henderson and the second to his daughter.

The argument with the landlord not withstanding, we must assume it was this second eviction that prompted the family's decision to emigrate. Family stories claim that Arthur and Margaret chose Australia on the advice of their eldest son James. There is no record of James visiting Australia before 1865, but he would probably have heard about the country from other seaman with whom he worked. The family’s decision may have been influenced by the visit to Shetland in 1849 of Dr John Dunmore Lang who was a Presbyterian Minister and member of the New South Wales Legislative Council. He preached to large crowds in Stromness and Lerwick encouraging emigration to Australia. Lang was particularly keen to encourage Protestant female emigration as a way of redressing the disproportionate numbers of males and Catholics in Australia. 10

Lady Jane Franklin, who was Vice-President of the Ladies Female Emigration Society of London, was also in Shetland in 1849, hoping to hear news of her husband’s Arctic expedition, (see Appendix 1). There appears to have been some link between Lady Franklin and the Robertson family and we can only speculate whether she may have assisted or encouraged the family's emigration. Where the family resided between the time of their eviction and their departure for Australia we do not know. Nor do we know how and when they travelled to their departure ports of Liverpool and Plymouth. All we can be certain of is that Arthur Jnr was still in Shetland in January 1866 when he registered the death of his grandmother, Barbara Manson.

View across Whiteness to Weisdale Voe

1. I am indebted to Thelma Watt and other members of the Shetland Family History Society for helping me chase up our Shetland connections.

2. See bibliography

3. The potato famine in Ireland and the effect it had on Irish emigration is well known. Less well known is that the same crop failure, caused by the potato blight, affected Scotland and Shetland, where crofters were also reliant on potatoes as a staple food. The years 1846-1849 saw a series of crop failures. J. Nicolson, Traditional Life in Shetland, p.28 tells us that in the 1840s, “to prevent famine the British government, through the Board for the Relief of Highland Destitution began a programme of road building. The workmen being paid in meal." [Seems there is nothing new about work for the dole.)

4. Shetland did not become part of Scotland until 1469 when the King of Denmark pledged Shetland and Orkney as part of his daughter's dowry on her marriage to the future James III of Scotland.

5. From Lottie Dickins

6. Notes written by John Collins McCue supplied by his daughter Helen Krigsman

7. Shetland Archives

8. lbid

9. Extracts from eviction notice dated October 1862, see Chapter 1

10. N. Kendall. With Naught But Kin Behind Them, Chapter 16

Garry Gillard | New: 5 March, 2019 | Now: 5 September, 2022