The Folk from the Wind Wound Isle > Life in Australia

page 23

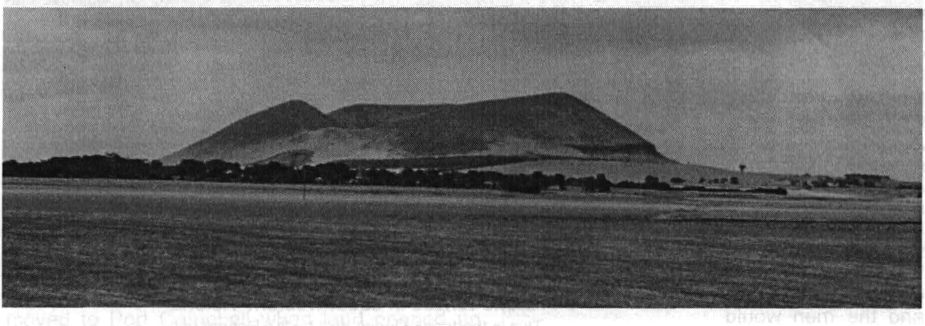

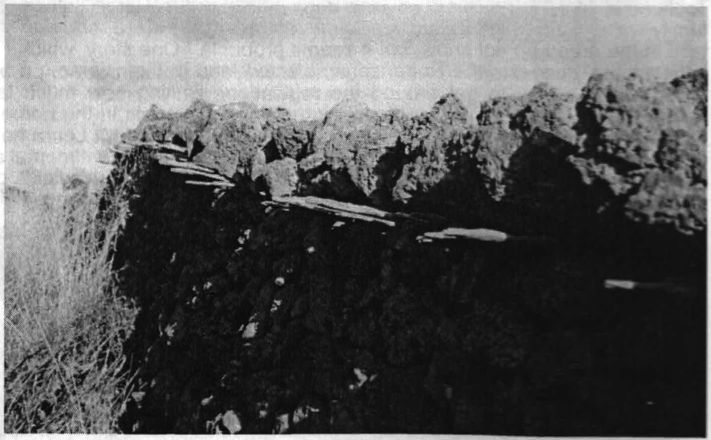

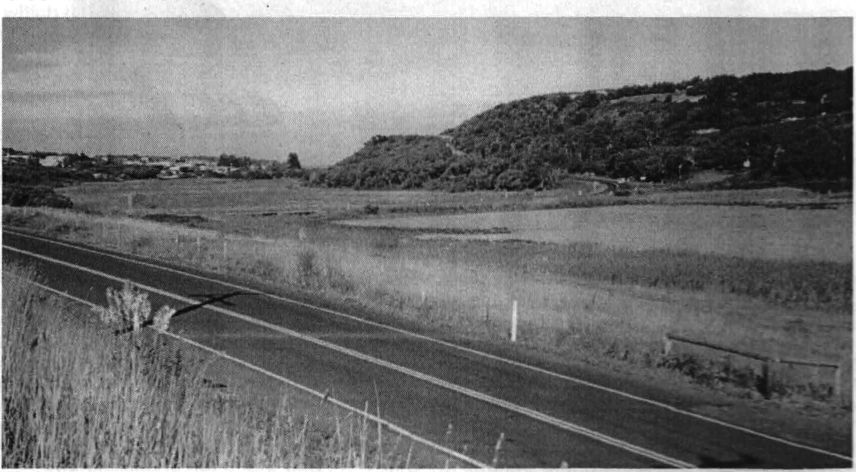

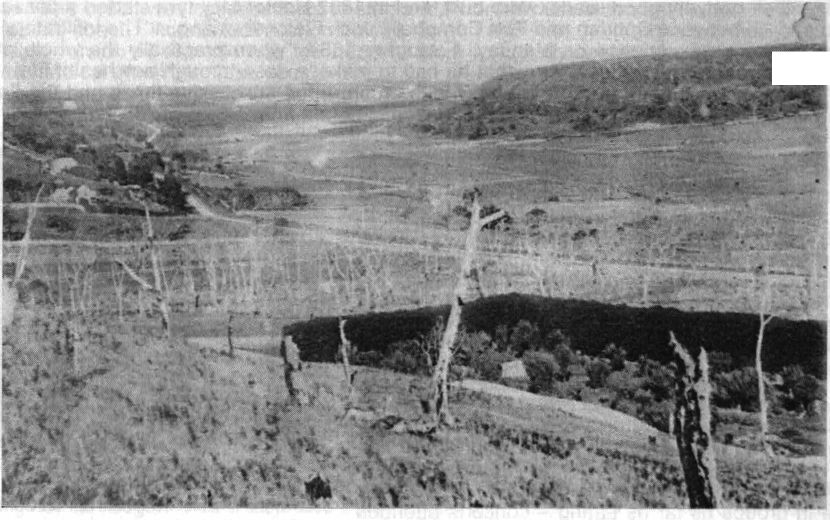

Mt Elephant: A recent view

As family members joined Arthur in the western district of Victoria the family settled at Lake Tooliorook near Derrinallum. 1 It was here that the eldest son, James, married in 1868. The family was still there in 1870, when Agnes and Margaret were married. Whether Arthur took up land in the area I do not know, but it seems probable. One story, which l have not been able to substantiate, suggests the Robertsons selected land in their name, on behalf of people called Manifold, as a ploy to get around the regulations limiting how much land one person could select. Lands department records show there were five lots in the name of J Robertson in the township of Derrinallum in 1867. Mt Violet, Mt Elephant and Mt Leura have all been suggested as a possible site for their first home. Certainly Robert had a sentimental attachment to the area where he spent his teenage years, writing a song about Mt Leura’s fields of green, “There an old slab cottage stood / In a gently sloping wood” 2

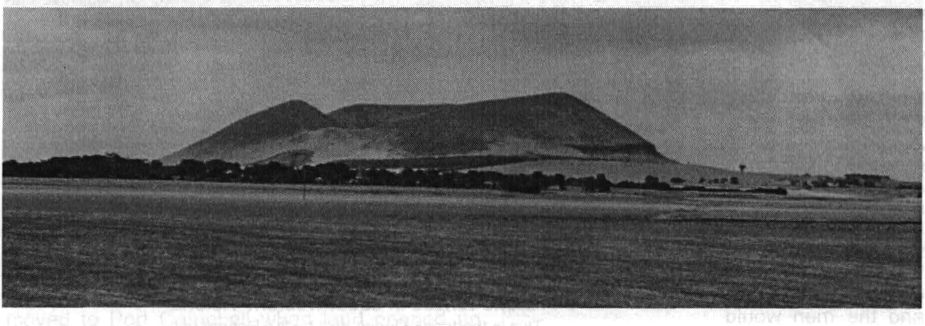

'Mt Leura's fields of green'

By the year 2000 the “gently sloping wood" has almost diappeared and European poplars have been planted.

Arthur must have quickly realized the potential for earning a living by building dry stone walls and sheds, a skill he and his sons brought from Shetland. The walls had the multiple advantage of providing fences for impounding stock, marking boundaries, providing fire breaks, and clearing the land of some of the millions of stones which dot the area as a result of volcanic activity in the long ago past. The Robertsons gathered around them a team of fence builders which undertook contract work for local landholders in the area around Camperdown, Derrinallum, and Skipton, east to Pomborneit in the Stoney Rises and as far west as Ellerslie and the Ballangeich and Drysdale homesteads. The stone fences at Larra Station were built by the Robertsons in 1869-70. This includes the stone gateway that was originally the entrance to the homestead, and which is now part of the public road. There is supposed to be a ‘signature’ mark on one of the stones but l was unable to find it when I visited the area in 2000. Those working with the Robertsons included Michael McCue, who would marry Agnes, and a man named Murnane, about whom l know nothing other than his name. 3 Progress was at the rate of ‘one and a half chains per day' and the men would camp out as they progressed along the extending fence line.

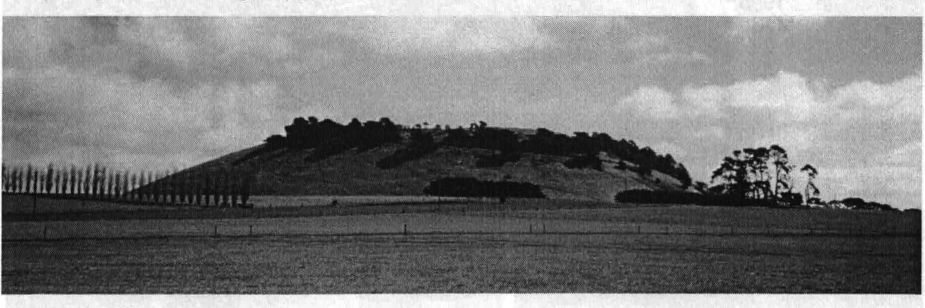

Stone fences in western Victoria.

This is the type of fence built by the Robertsons. >

Many of the stone fences in western Victoria are now protected under conservation legislation and the Corangamite Arts Council produced a book about the fences in 1995. 4 John McCue gives an account of Robertson involvement building the fences on page 83 of the book. An error in this account describes Arthur as John’s great uncle, when he was in fact referring to his great grandfather.

Stone fence with embedded wooden slats to deter rabbits >

Stone fence with embedded wooden slats to deter rabbits >

From Derrinallum the family moved to Port Campbell. The chronology of the move is not clear, but it probably took place over a period of time, with family members moving about south western Victoria as the menfolk took labouring jobs or did contract work fencing and shearing. Lonely for the sea, Arthur Robertson visited and selected land at Port Campbell as early as 1865, but did not take possession of it until 1871. Robert writes, “When father first visited Port Campbell it was a veritable ‘no man‘s land.’ The Government refused him the selection of land where the town now stands, reserving it for a town. Land further up the river was obtained, and there he built a five-roomed stone cottage." 5 This land, near to the cemetery, is on the northeastern side of the bridge over Campbell Creek. On the Lands Department map it is marked as Lots 10 and 10a, divided by the present road to Timboon. (See the map on page 32.)

It seems the family’s early efforts at farming in the Mt Violet area were not a success. Arthur is quoted as saying, ‘Come boys, if we can’t make a living from the soil, we’ll make it from the sea as we have always done.’ This is supported by a comment added to a report about James Robertson‘s land reproduced in Appendix 4, which refers to another file, [possibly one about Arthur's land?]. It states, “The applicant and his sons were fishermen or connected with fishermen in Scotland and their ambition is to found a fishing station at Port Campbell." The idea came to nothing, for the Port Campbell coastline, with its the steep dangerous cliffs and off-shore winds, was not suitable for a fishing industry.

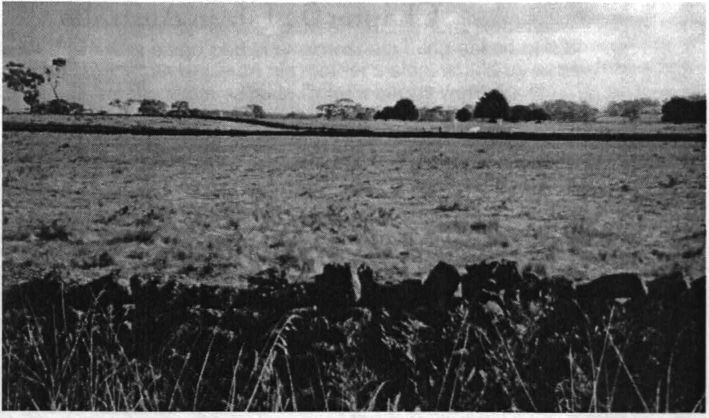

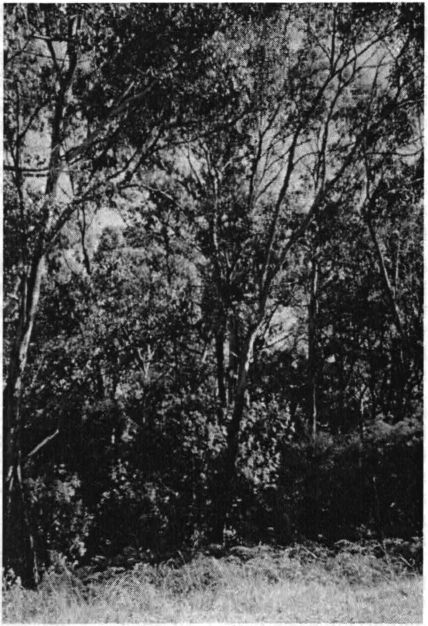

Heytesbury Forest >

A remnant section photographed in 2000. The area around Port Campbell was originally covered by dense forest which had to be cleared before crops could be planted.

Not everyone was happy with the move to Port Campbell and Lottie Dickins reported, “The family moved to Port Campbell when land opened up there because of their love of the sea - giving up better land and a better farm for poor land and virgin forest. Grandmother R was very upset as she did not wish to leave the district where they were established. All the women rode down side saddle through the Heytesbury forest - now cleared away and all farming land.“

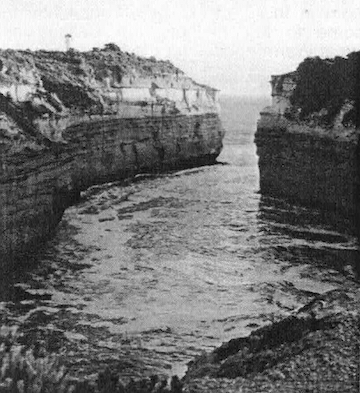

Several sources suggest that the choice of Port Campbell was associated with the cliffs, which reminded the family of the cliffs at Eshaness in Shetland. The Eshaness cliffs are black, in contrast to Port Campbell's yellow sandstone.

Eshaness on the west coast of Northmaven Shetland. — Loch Ard Gorge

near Port Campbell, Australia.

Margaret Henderson’s concern was probably well justified as descriptions of the early days at Port Campbell indicate a hard life. The isolation of the settlement and the difficulty of clearing dense forest and establishing crops such as potatoes and oats, meant food was sometimes scarce and families often went hungry. Obtaining supplies such as flour and tea involved a ride to Cobden - one day there, stopping overnight, and another back again. Robert writes, "... you must know there was no fatted calf which had ever been seen at Port Campbell in those early times. There was no grass to fatten a calf on.” However Arthur believed the area would prosper. "He tested his faith by making a small grass-tree area wallaby proof, digging it up, sowing oats and fertilizing it. He reaped a satisfactory return, which assured him that what he had done in a small way could, and would, be done in a large way some day” 7 Years later the use of super phosphate and trace elements would make the area more suitable for farming.

Neighbours of the Robertsons were Mr and Mrs Hector Mclntryre and Mr and Mrs John Henderson (not related to Margaret). The families became friends, giving each other support through difficult times, particularly the women who were often left on their own when the men were away working. The Mclntyre’s daughter was the first white child born in the area and Margaret attended her birth. The first death at the Port was the Henderson’s child, “which cast a shadow over every heart in the settlement.” 8

Arthur quarried stone out of the cliff near the lower section of the present cemetery, rolled it down the hill, cut it into suitably sized blocks, burned the lime, slacked it and mixed it, and built a substantial five roomed house for his family. lt became known locally as ‘the old stone house’. There is an old photo showing section of the house and a painting by Miss Maud Brown hanging above Di and Jeff McCue’s dinner table at Port Campbell. A more recent representation of the house was painted by Valerie Ward shortly before her death in 1990 and hangs in Gus Ward’s house.

The Old stone House. >

The Old stone House. >

An early photograph of Port Campbell showing the bridge over Campbell Creek and a section of the Robertson's house. This photograph was used by Francis Robertson Saunders on the cover of her tract ‘My Grandmother's Prayer’.

While the house was being built, Arthur and Margaret lived in a 6 x 3 feet (roughly 2 x 2.5 metres) tent in the cavity from which the stone had been excavated. Agnes’ daughter, Robina McCue, was born in this tent in 1872, Agnes having come to her mother from Ballangeich (near Warrnambool) for the birth.

The stone house was completed in July 1872. The local stone was not the most ideal building material and a verandah surrounding the house was essential to protect it from the weather. Despite this protection the stone absorbed moisture and for much of the year the walls were green with damp. The stone house was eventually demolished. Margaret Haine remembers seeing piles of stones were the house had stood, when she was in Port Campbell in 1926. All the Robertson brothers selected land along the Campbell Creek valley, as did Michael McCue and George Chislett, who married into the family. The report mentioned previously, written by a mounted constable after his inspection of James’ block in July 1874, tells us the area was ‘heavily timbered and covered with dense scrub’. Robert describes an evangelising visit to the Mclntyre’s house at about this same date, “He at that time was a shepard [sic at Glenample where the wild dogs were troublesome to the sheep. Mrs Mclntyre appraised her husband of the proposed visit. Arriving at the hut we found him standing with his back to a log fire, shirted and trousered, with a saddle strap round his waist, his feet in unlaced boots.” 9

The lives of the second generation in Australia fall into two phases divided by the religious revival of 1874. The division is not sharp and I am sure the change from hard living settlers, struggling for survival, to respected God-fearing preachers, occurred more gradually and over a longer

page 27

period than Robert Robertson, writing in ‘The Port Campbell Revival’, seems to indicate. I write about the Robertsons and Christianity in Chapter 13.

Robert not only relates the Robertson family’s spiritual conversion, but he also gives us glimpses of the environment in which the family lived:

... homes scattered through the forest in winter time the bridle tracks were just streaks of gutters. There were no roads, no bridges and no culverts. Swamps, rivers and creeks were all full of water. To cross at the mouth of a river on a moonless night when a storm was on was to me rather gruesome. The river one was crossing always seemed to be much lower than the thundering breakers roaring outside. It seemed as if the horse and yourself must be overwhelmed. The waters were swirling around the horse’s legs as he waded through, and the sands under his hoofs were in constant motion. At such times I always had a feeling my horse was sensitive of danger. He and I were always glad when we were safely over. 10

Stories suggest a wild undisciplined bunch in the early days. There is certainly enough anecdotal evidence to suggest the Robertsons were heavy drinkers, with whisky their preferred drop. Lottie stated, “All the Robertsons were heavy whisky drinkers except Robert who was unable to drink because it made him ill. Uncle Willie and Jim and the sisters gave up drinking after becoming religious?" 11 Unlike his brothers Arthur Jnr continued drinking alcohol and Lottie told of living with her Uncle Arthur and Grandmother cum Aunt, Margaret Rutherford Cairns Robertson at Port Campbell, to help look after Margaret in her old age. Arthur would come home drunk and Lottie was terrified he would set the house on fire as he staggered around with a candle.

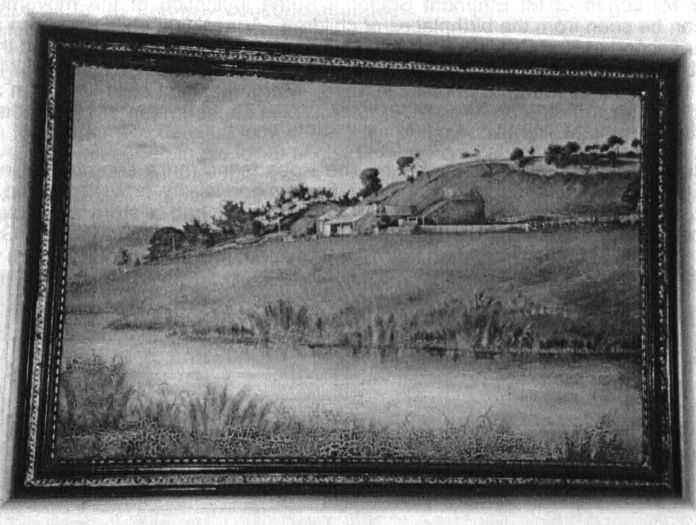

The Old Stone House

Painted by Miss Maud Brown in the 1880s. Note the scorch marks around the frame, which suggests the painting has been through one of the house fires mentioned in Chapter 7.

The Rev Jack McCue, when telling his daughters Marjorie and Marion about his childhood, related that the Robertsons were often so drunk they could hardly stand up. As a child, Jack would be put to sleep with a nip of whisky. It was Jack’s early experiences with the effects of the demon drink that turned him into an ardent temperance worker in later life. It certainly appears as if Michael McCue continued drinking heavily all his life and this might have been a point of contention between him and Agnes.

There are two stories about Robert in his late teens or early twenties. The first incident resulted from a disagreement with the local innkeeper. Robert rode his horse into the bar and with his whip he knocked all the bottles off the shelves. The second story involves the local coach

page 28

service. The coach was not scheduled to stop and Robert’s companion bet Robert £10 he could not stop the coach. Robert took him on, raised his gun and shot the lead horse. A slightly more charitable version of this tale has the need to stop the coach because a woman giving birth needed medical attention. Take your choice, either way the horse ended up dead.

In writing about his parents’ Christian faith and the family prayer sessions, Robert himself seems to make a small admission about his parent’s concern for their children's lifestyle by stating, “ln spite of prodigality, [their] prayers were priceless and painful to kick against. From the conversion of my parents until the salvation of their family would be over thirty years, giving a long time of prayer for these two.” 12

Lottie Dickins gives us a Cairns’ view on the Robertson family. Her mother and Uncle Sam, both Cairns, told her “the Robertson clan was very strong, which was never overcome and they shared the good and the bad. On one occasion they turned up at the Cairns property at Skipton and killed a milking cow for a feast. lf one of them experienced good fortune the others expected to share it and when one lot was having a hard time they would call on another family member to support them.” 13 This closing of ranks sometimes made it difficult for outsiders to be accepted. Arthur Snr made no secret of his hatred of the Sassenach - a term covering the English and Lowland Scots - and he proudly proclaimed his Norse descent. It seems Mick McCue, an Irish Catholic, had trouble being accepted by the family. Jack McCue claimed his grandfather never spoke to him when he was a child.

While the land was being cleared and crops established, other sources of income must have been needed and at the time James’ land was inspected in 1874, he was away from home, working for Mr Logan of Mt Elephant Station. Some indication of the movement of family members can be seen from the birthplaces of children. Agnes’ first child was born at Tooliorook in 1871, her second at Port Campbell in 1872, her third at Tooliorook in 1873, and the last two at Port Campbell. James’ first two children were born at Darlington in 1869 and 1871, the third at Cobden in 1873 and his fourth at Ellerslie in 1876. Margaret’s first child was born at Tooliorook in 1872 and her second at Ellerslie in 1876, her fourth in Melbourne in 1879 and the rest at Port Campbell.

Gradually the settlement began to prosper. The Robertsons ran a shop in the lean-to on the southern side of the house, supplying drapery, leather goods, dry provisions, and home made cider. Lottie related that in the early days, “Grandfather R had a store and sold cider. The excise officer Harrison analysed the cider and found it an intoxicating drink and Grandfather R was fined? 14 A similar story is attached to William Adie, but this time involving plum wine. These could be different versions of the same incident.

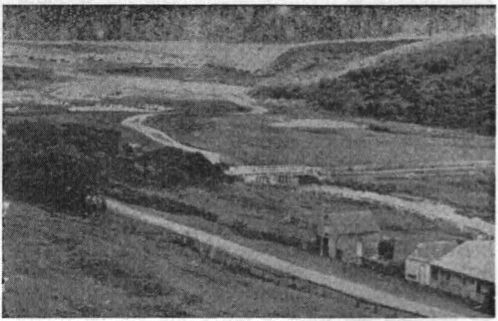

Present day view of Port Campbell and the site of the Old Stone House

page 29

Roads, albeit not very good roads, were built, and in 1882 Hector Mclntyre started a passenger coach service between Cobden and Port Campbell. Jack Fletcher writing in ‘The lnfiltrators’ tells of Mr McIntryre’s experience on Monday, 4 January 1887, “when practically the whole of the forest was on fire. The records show that he had to make "a dash through patches of fire which walled up each side of the road; the buggy was on fire three successive times and the flames extinguished, and the seat was burnt from beneath him before he reached his destination". 15

In 1888, the newly built community hall was used as a polling place for elections. The original ballot box is in the Port Campbell museum with a notice attached to it saying Arthur Robertson acted as polling clerk. ln the 1890s a shed attached to the old stone house was used by Bill Port as a cobbler’s shop. This was probably the same lean-to used earlier as a shop. Bill was an uncle of Jessie Port, wife of Arthur Ward in Generation ‘D’. He died in the middle of the decade at the age of nineteen or twenty from a ruptured appendix.

Ballot box >

Used in the first elections held at Port Campbell

John McCue writes that Arthur “went to Warrnambool regularly crossing the Curdies River at Peterborough. If the travelling was by horseback, the shorter trip was taken by Boggy creek - the horses ‘swum’ over and a break often made at the Le Couteurs. Trips were made in groups as far as Laang - concerts attended and contributed to. Horses were traded - cattle exchanged or sold - families intermarried - a new strata of living was established.“ 16

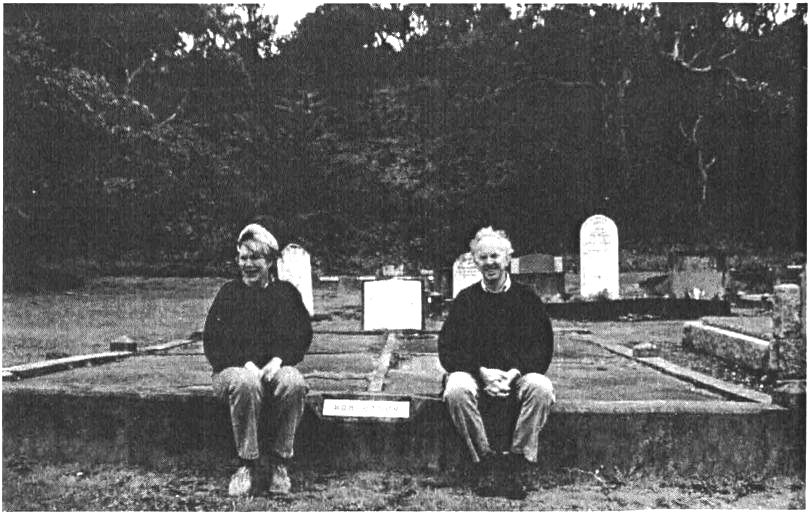

With the coming of the new century, we leave Margaret Henderson and Arthur Robertson behind and move on to take a more detailed look at the lives of their children. Margaret died at the age of seventy-five and was buried in the lower section of the Port Campbell cemetery on 26 October 1887. Arthur would live for another nine years. He died at the age of eighty-one and was buried beside his wife in the family grave on 30 December 1896. Other members of the family would later join them there.

Robertson Family Grave, Port Campbell Cemetery

Seated on the grave are Graeme and Heide Robertson.

page 30

An early view of Port Campbell from the hill

1. The name of the settlement called Tooliorook was later changed to Derrinallum.

2. See Appendix 5 for the full text of ‘Mt Leura's fields of green’.

3. The Murnane name appears quite frequently in histories of the Heytesbury Shire.

4. J. Black, ‘lf These Walls Could Talk - A report of the Corangamite dry stone walls conservation project’

5. R. Robertson, ‘The Port Campbell Revival', p.49

6. Lottie Dickins recorded by her daughters Marie Nemec and Margaret Worrall

7 R. Robertson, ‘The Port Campbell Revival’, p.13 and p.49 respectively

8 lbid, p.8

9 lbid, p.17

10. R. Robertson, ‘The Port Campbell Revival’ pp.7-8

11. Lottie Dickins recorded by her daughters Marie Nemec and Margaret Worrall

12. R. Robertson, ‘The Port Campbell Revival’, p.7

13, Lottie Dickins recorded by her daughters Marie Nemec and Margaret Worrall

14. lbid. According to Lottie, Harrison was the great grandfather of a General Harrison and Harrison family lives often touched Robertson family lives.

15. J. Fletcher, ‘The Infiltrators - a History of the Heytesbury 1840-1920’, p.97

16. Notes made by John McCue

Garry Gillard | New: 5 March, 2019 | Now: 31 March, 2019