List of Maps

Prologue

Part I : Shetlanders

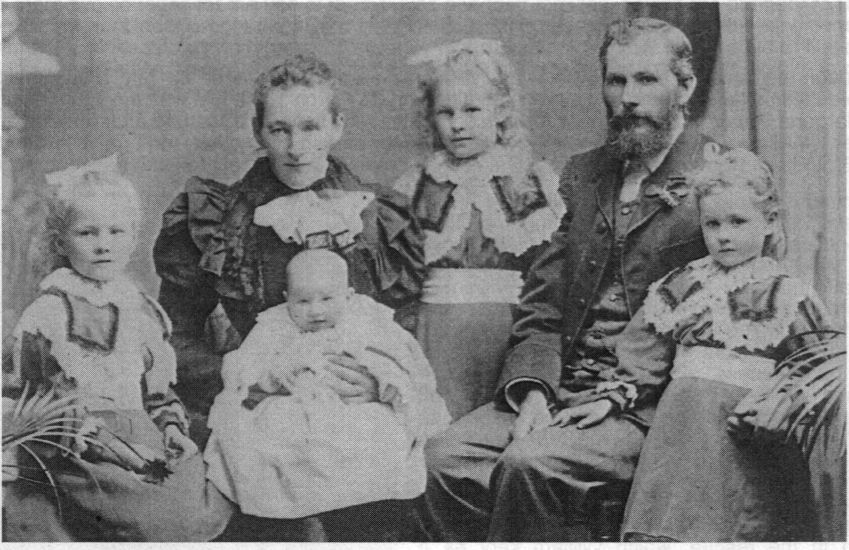

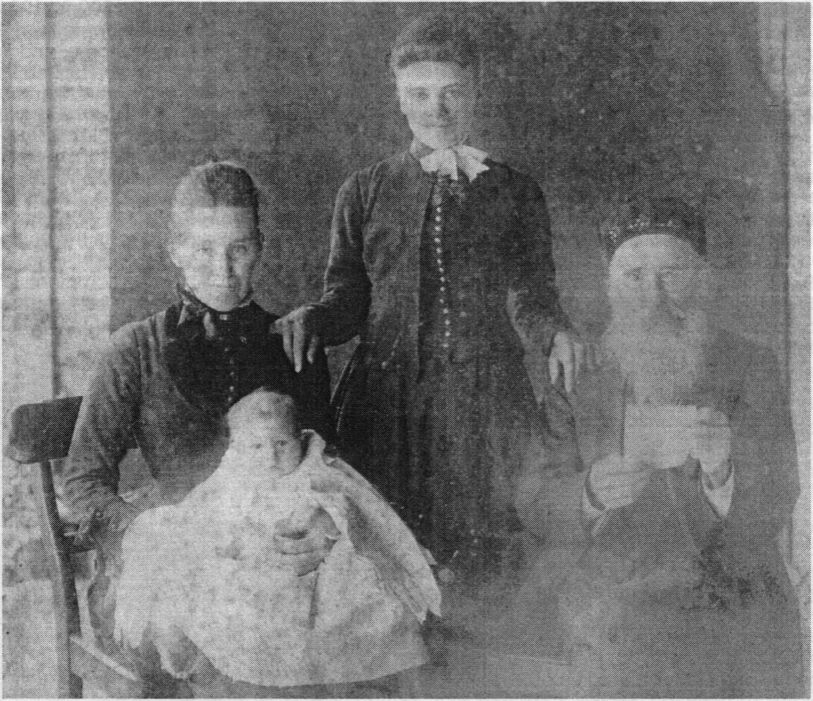

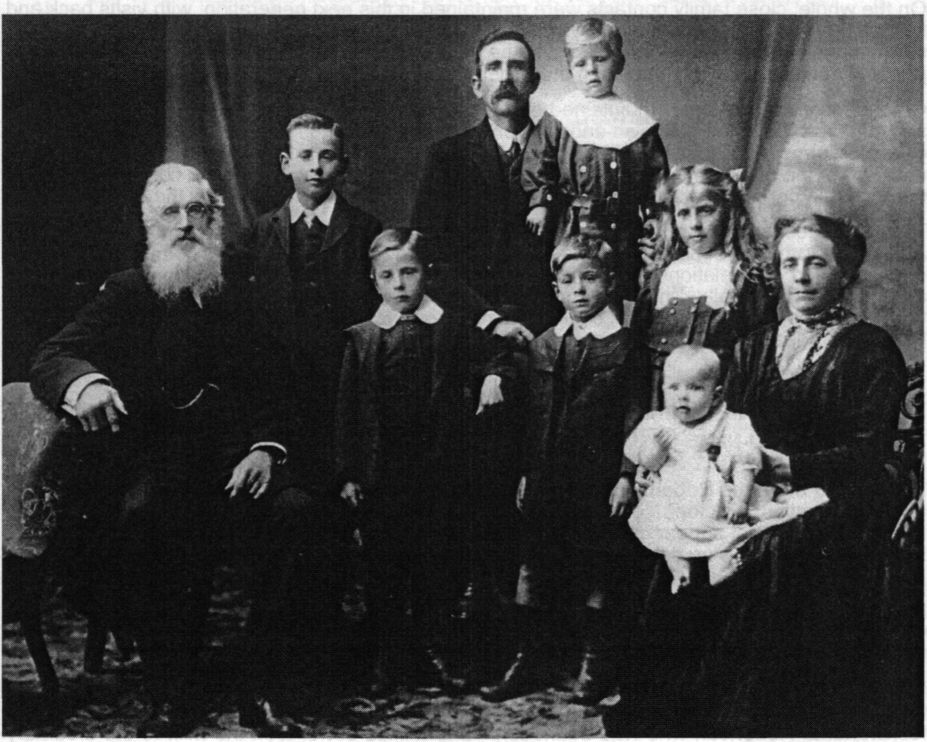

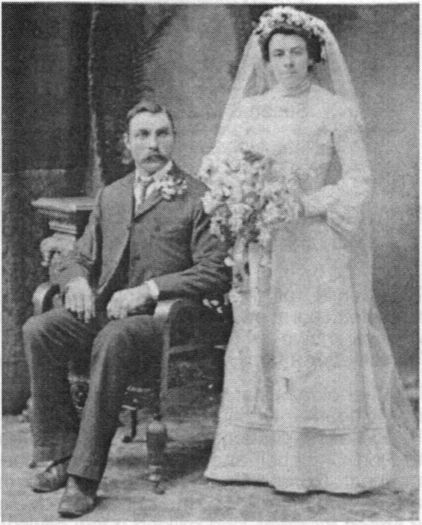

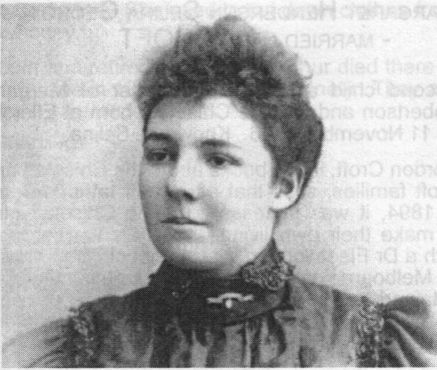

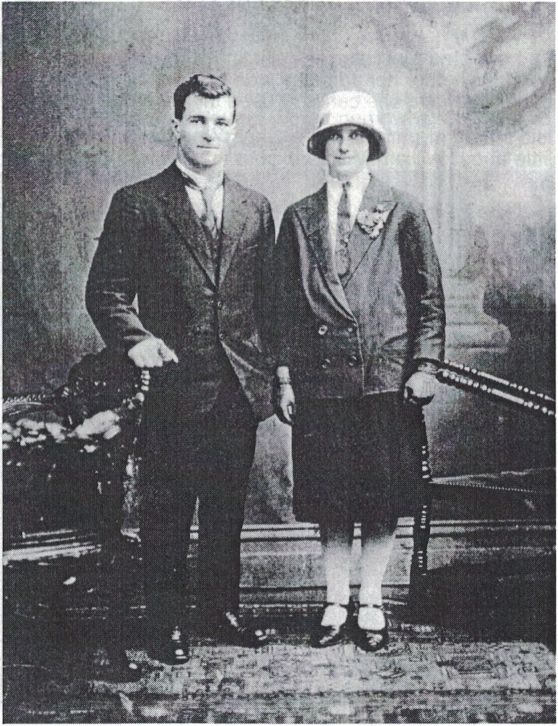

Chapter 1 : Margaret Henderson & Arthur Robertson

Chapter 2: Coming to Australia

Chapter 3: Let’s Go Backwards - the Robertsons in Shetland

Chapter 4: Barbara, John and Peter Robertson

Interlude

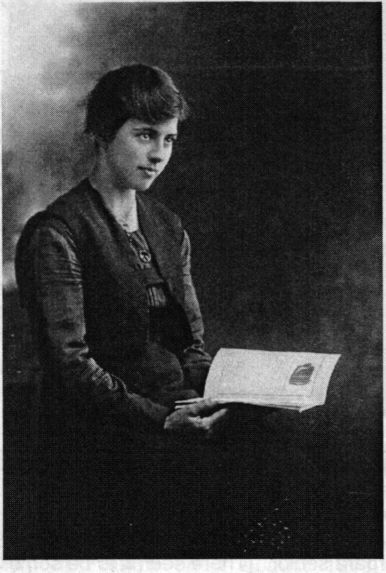

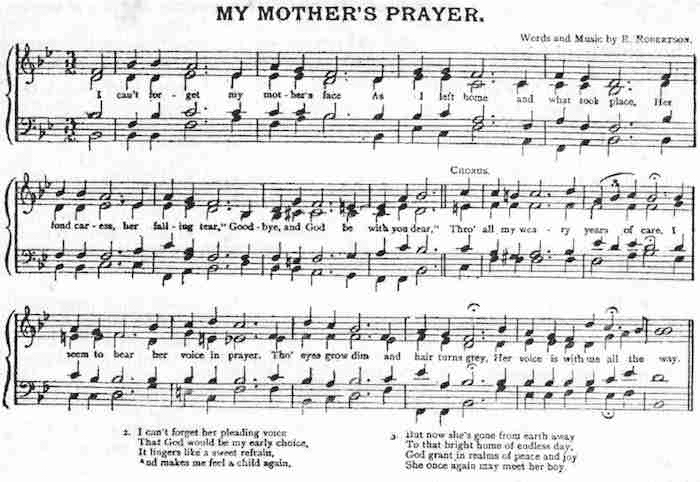

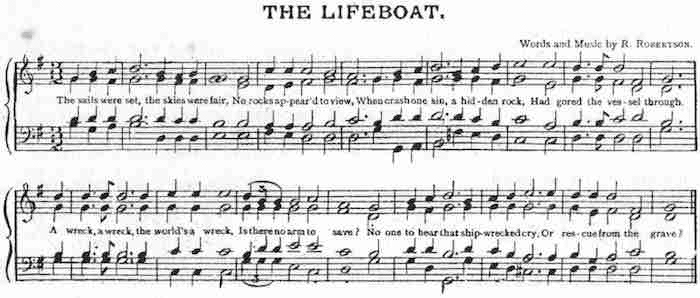

Chapter 5: The Gift of Music

Part II: Settlers

Chapter 6: Life in Australia

Chapter 7: Generation B - Agnes Robertson

Chapter 8: Generation B - James Robertson

Chapter 9: Generation B - Arthur Robertson Junior

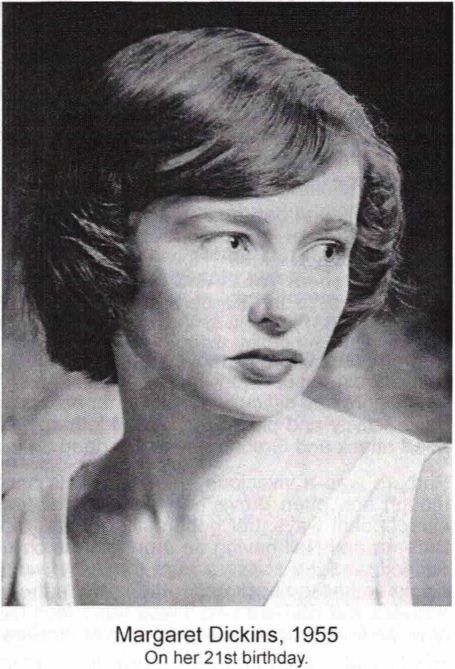

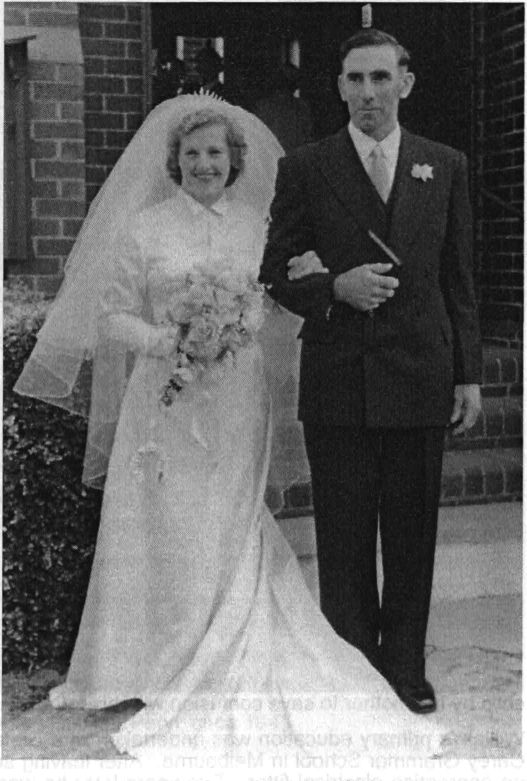

Chapter 10: Generation B - Margaret Robertson

Chapter 11: Generation B - Robert Robertson

Chapter 12: Generation B - William Adie Robertson

Interlude

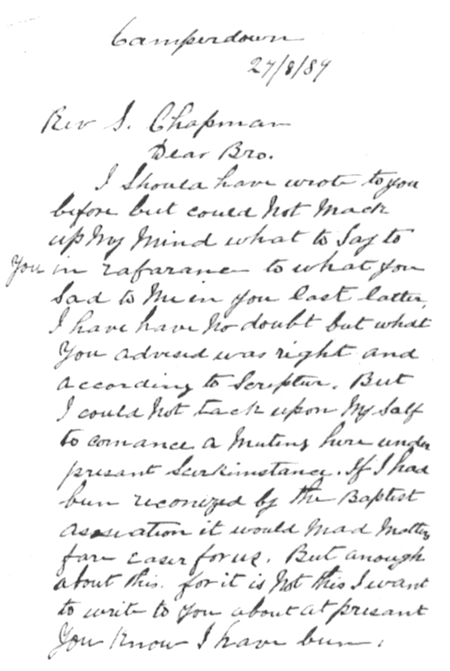

Chapter 13: The Robertsons & Christianity

Part III: Native Born

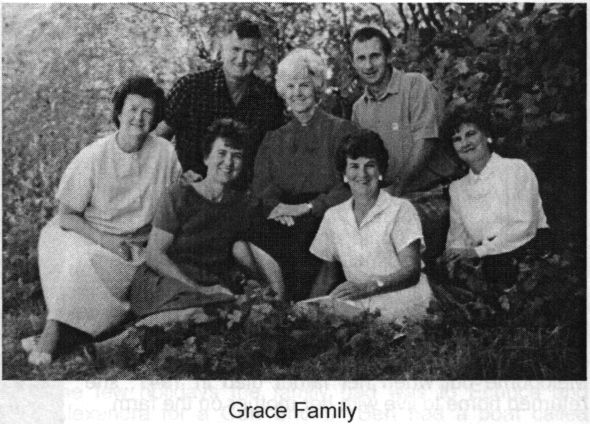

Chapter 14: The Children of Agnes Robertson & Michael Grace McCue

Chapter 15: The Children of James Robertson & Frances Halls

Chapter 16: The Child of Arthur Robertson Jnr & Margaret Rutherford

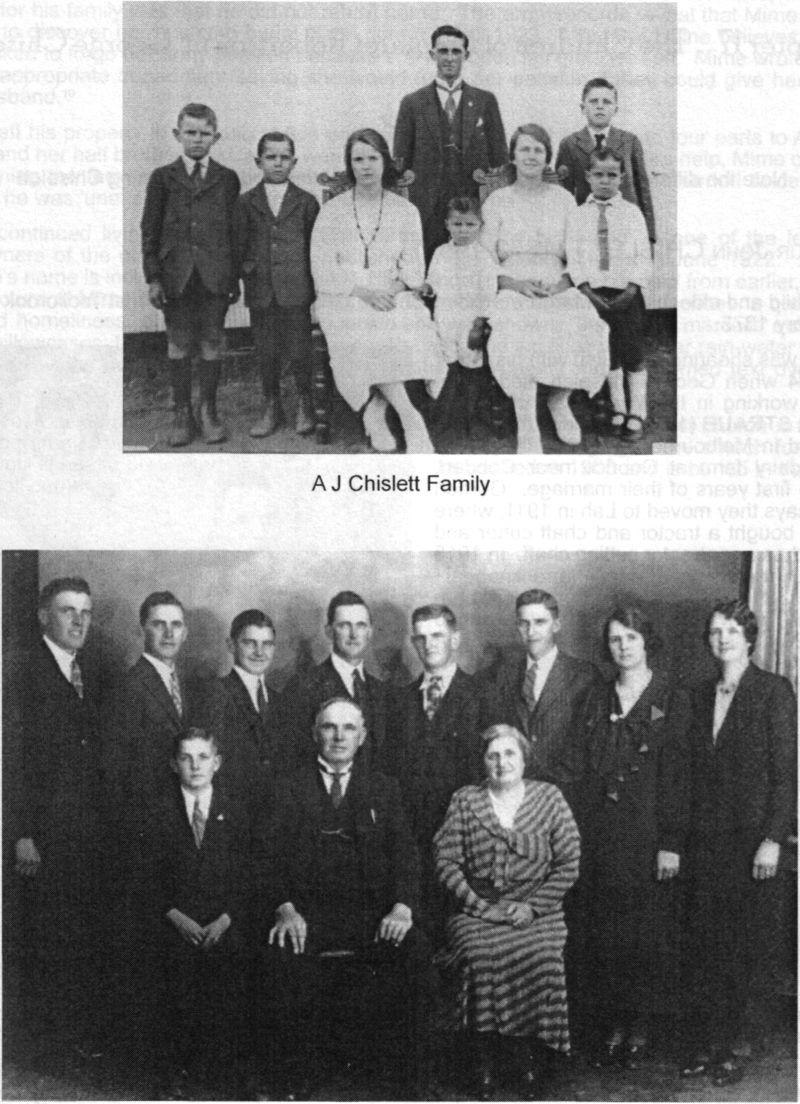

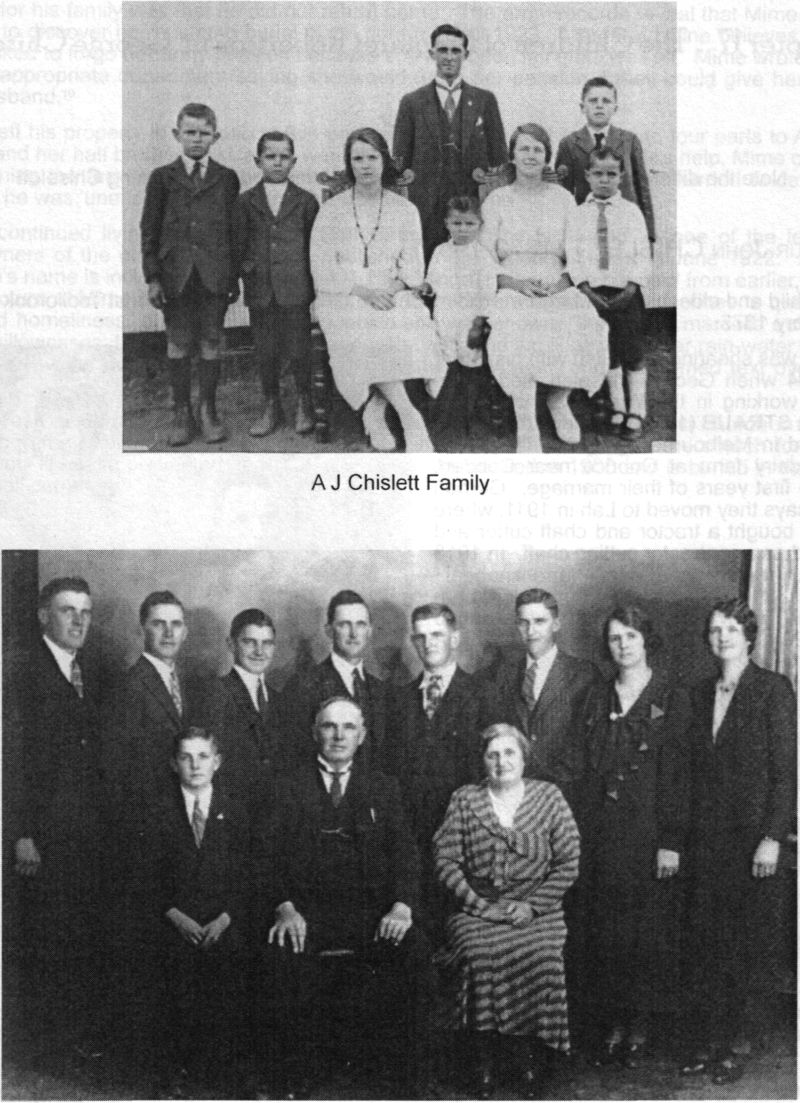

Chapter 17: The Children of Margaret Robertson & George Chiselett

Chapter 18: The Children of Robert Robertson & Mary Jane Cairns

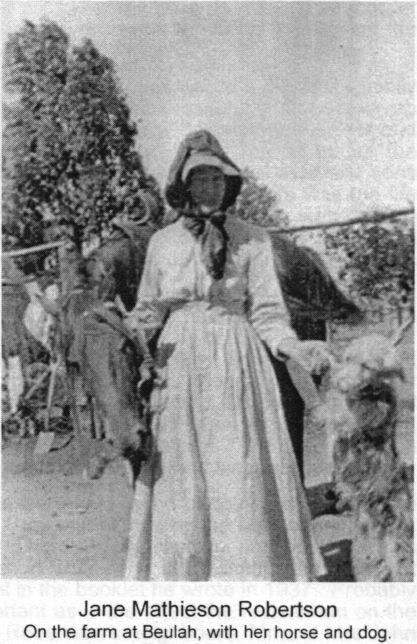

Chapter 19: The Children of William Adie Robertson & Jane Mathieson

Interlude

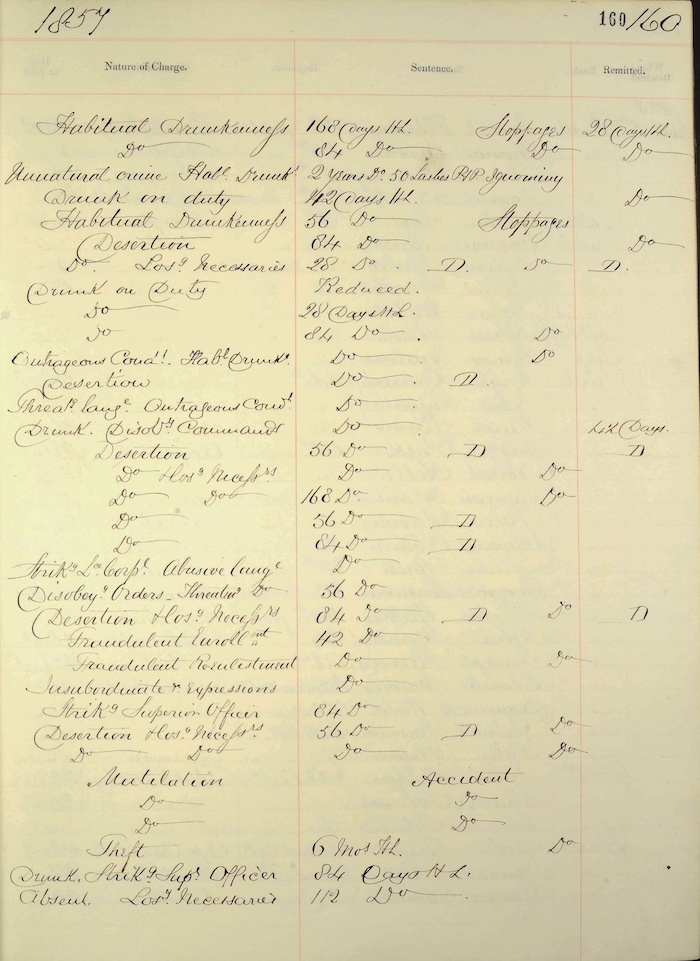

Chapter 20: The Robertsons & the Demon Drink

Part IV: Dispersal

Chapter 21: The Descendants of Agnes Robertson McCue

Chapter 22: The Descendants of James Robertson

Chapter 23: The Descendants of Arthur Robertson Junior

Chapter 24: The Descendants of Margaret Robertson Chiselett

Chapter 25: The Descendants of Robert Robertson

Chapter 26: The Descendants of William Adie Robertson

Interlude

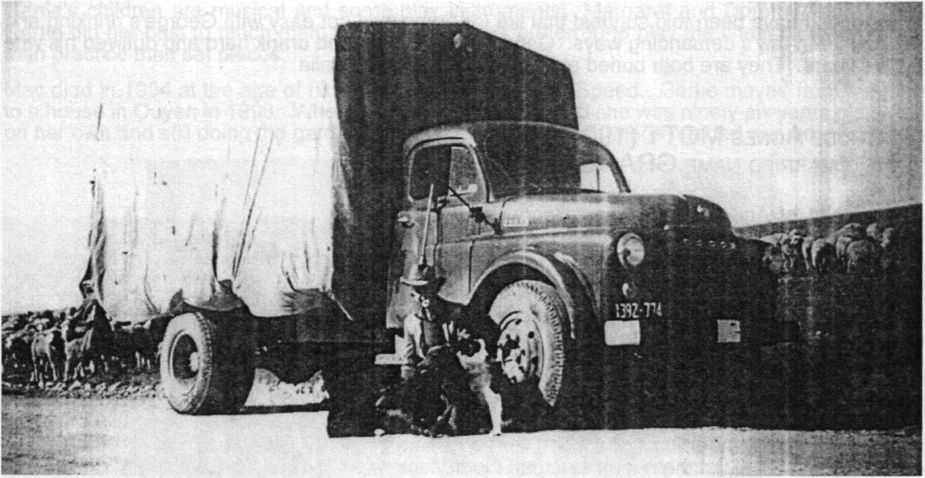

Chapter 27: Occupations, Arts & Crafts

Epilogue

Genealogical Charts

Notes on the Genealogical Charts

I: Chart of Descendants of Agnes Robertson

II: Chart of Descendants of James Robertson

III: Chart of Descendants of Arthur Robertson Junior

IV: Chart of Descendants of Margaret Robertson

V: Chart of Descendants of Robert Robertson

VI: Chart of Descendants of William Adie Robertson

VII: Table of Descendants of Margaret Henderson & Arthur Robertson

Appendix 1

The Franklin Expedition to find the North-West Passage, 1845-48

Appendix 2

Children of John McCue and Margaret McDonald

Appendix 3

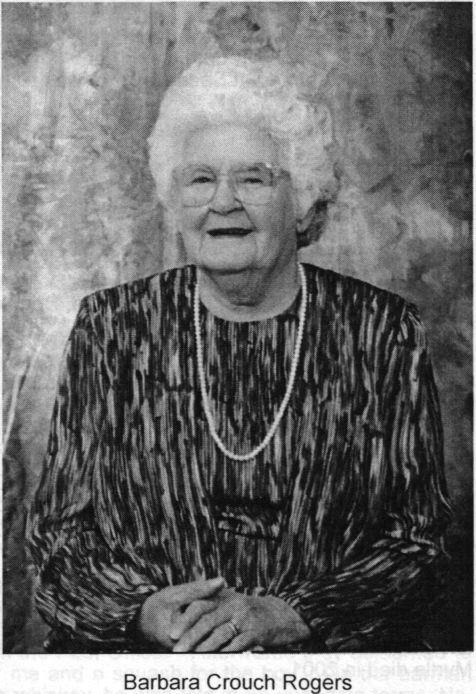

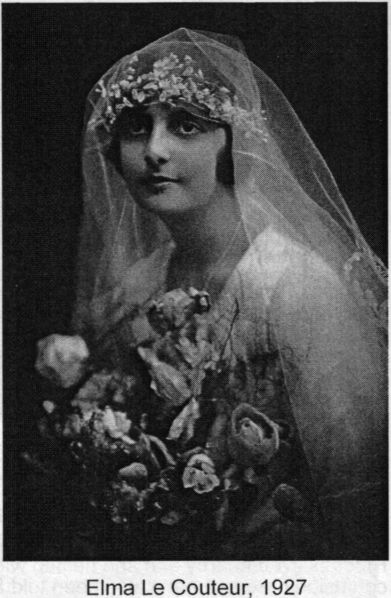

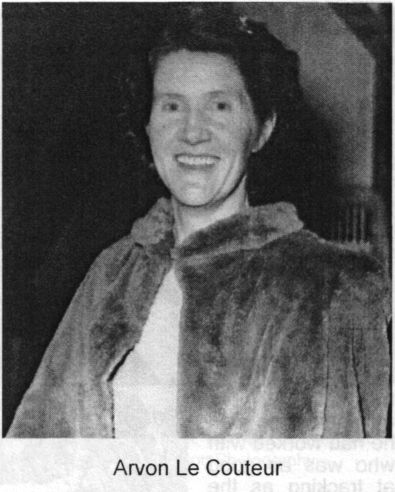

Linking Robertson - McCue - Mathieson - Le Couteur - Crouch - Croft

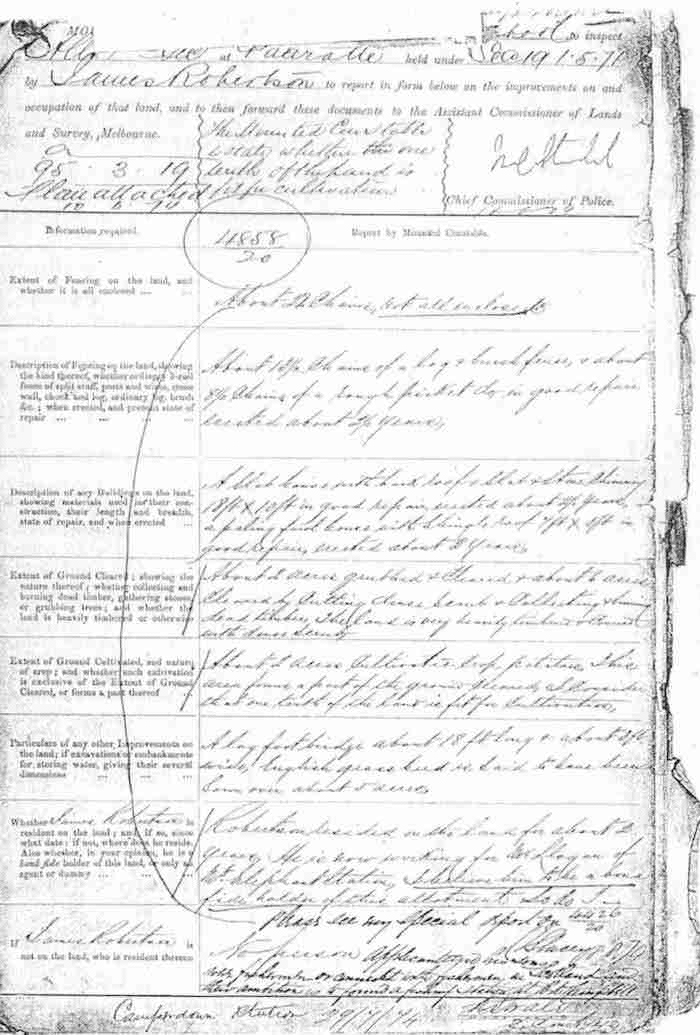

Appendix 4

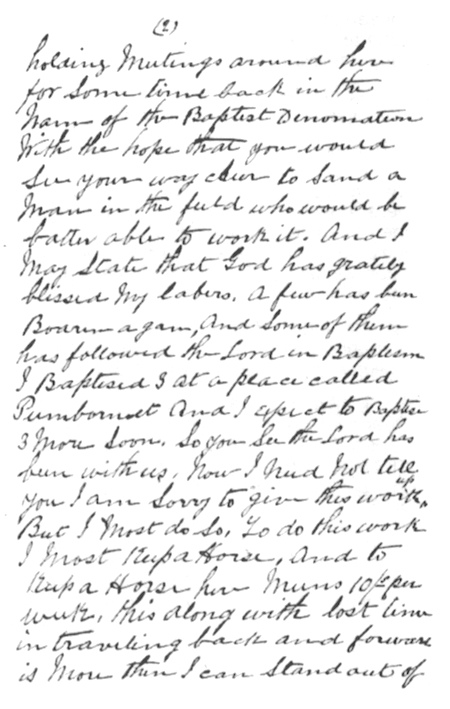

James Robertson Lands Department Document July 1874

Appendix 5

Writings, Sayings & Other Bits and Pieces

Acknowledgements and Resources

Bibliography

© 2004 Margaret Dawne Worrall

Published by Marie-Claire Nemec, Whitfield, Cairns

Printing by Cairns Plan Printing Services Pty Ltd,Cairns

Edited by Jessica Worrall

Front cover illustration © 2003 Joy Stewart

Indexed by Jessica Worrall

Interior design and production by Jessica Worrall

Maps by Margaret Worrall

All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research or review as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the author.

The National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication

Worrall, Margaret, 1934-2022.

The Folk from the Wind Wound Isle : The story of Margaret Henderson and Arthur Robertson and their descendants in Australia.

Bibliography.

Includes index.

ISBN 0 95818091 1

1. Robertson, Arthur, 1815-1896. 2. Henderson, Margaret, 1812-1887. 3. Robertson family. 4.

Henderson family. 5. Shetland (Scotland) - Genealogy. 6. Australia - Genealogy. I. Title.

929.20994

This online version is published with the permission of the author, Margaret Worrall, and editor, Jessica Worrall.

This family history is dedicated to Thelma Watt, of the Shetland Family Historical Society, who started me on the quest to find my relations, to my daughters, Lisa, Tracy and Jessica, and to my grandchildren, Nicholas, Lucy, Amy, Felix, Elisabeth and Charlotte, in the belief that they can learn from those who have gone before.

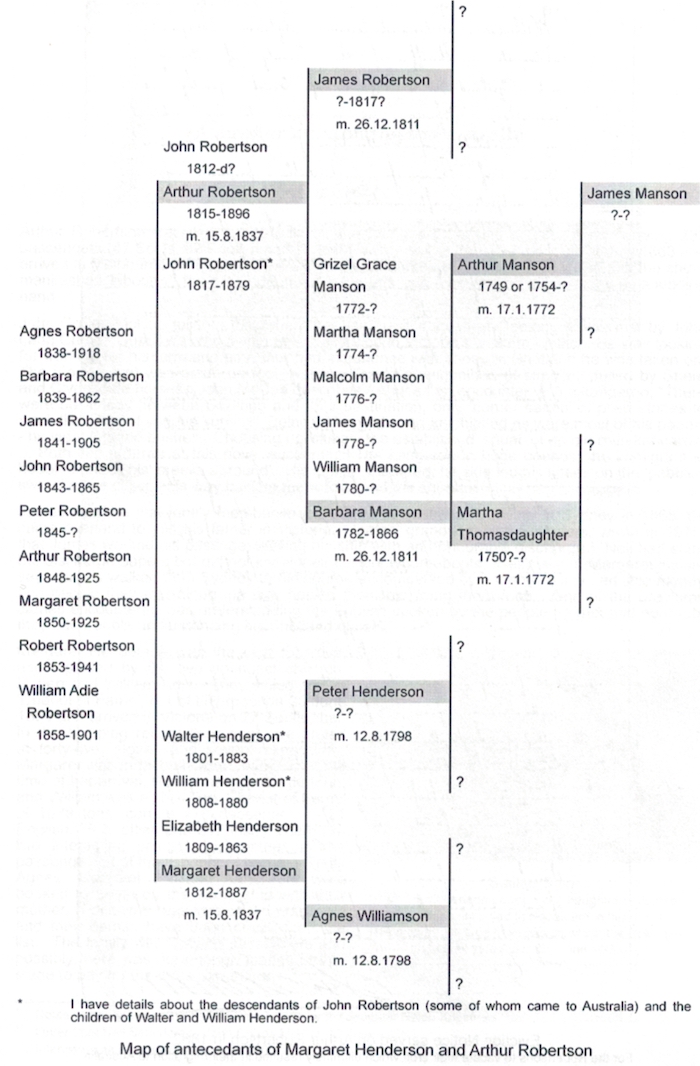

Map of antecedants of Margaret Henderson and Arthur Robertson

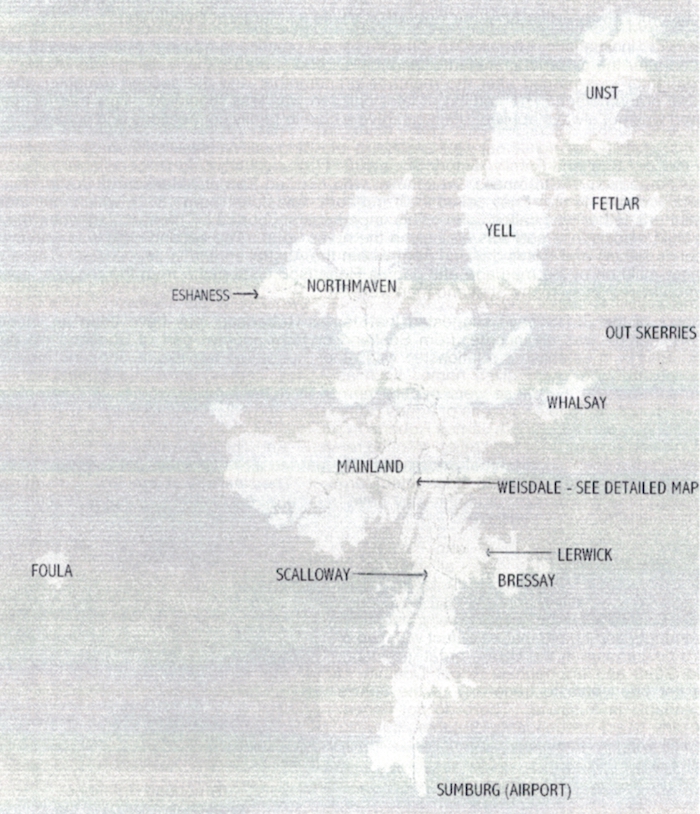

Map of Shetland

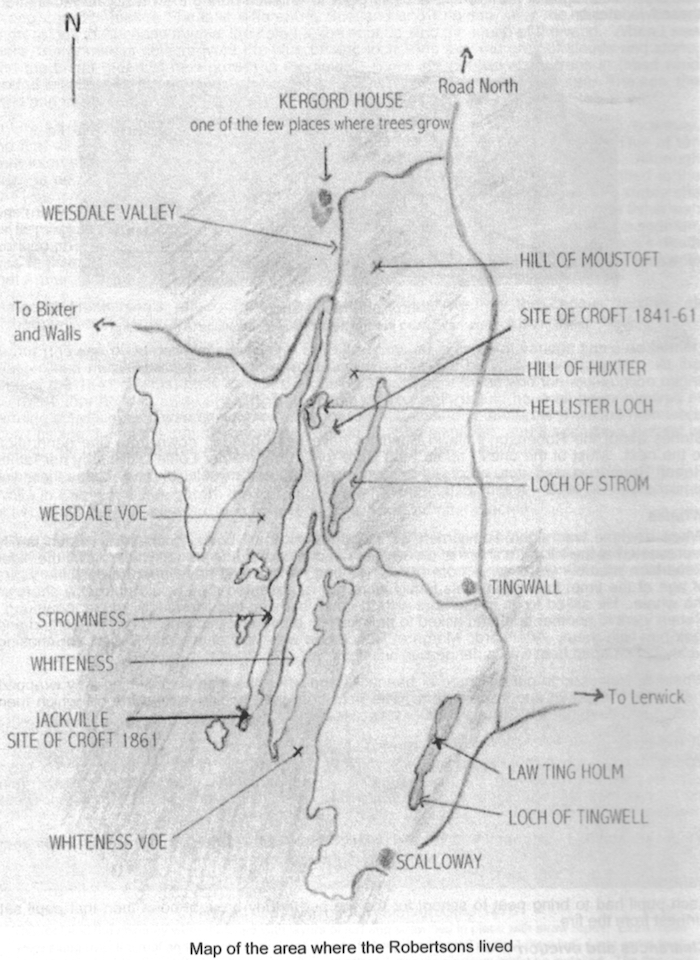

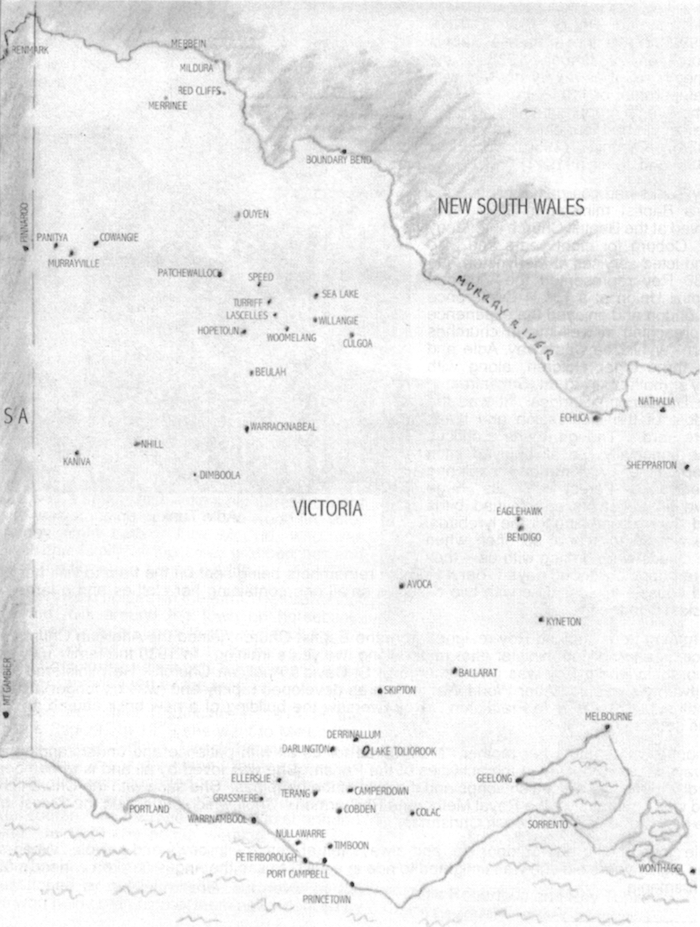

Map of the area where the Robertsons lived

Map of Port Campbell

Map of relevant towns in Victoria, South Australia and New South Wales

In 1997 I made a trip to Europe. One of the ‘must visit’ places on my list was Shetland, for I was curious about the place my grandfather had come from. Brother Mac had been following up a bit of family history in a rather on and off manner for some years, so I offered to see what I could discover about the Robertson family while I was in Shetland.

As a result of that short trip to Shetland - which I have written about elsewhere - I started on a much longer journey in search of relations I had not seen since I was a child, had only heard other people talk about, or whose existence I knew nothing about until I went looking for them.

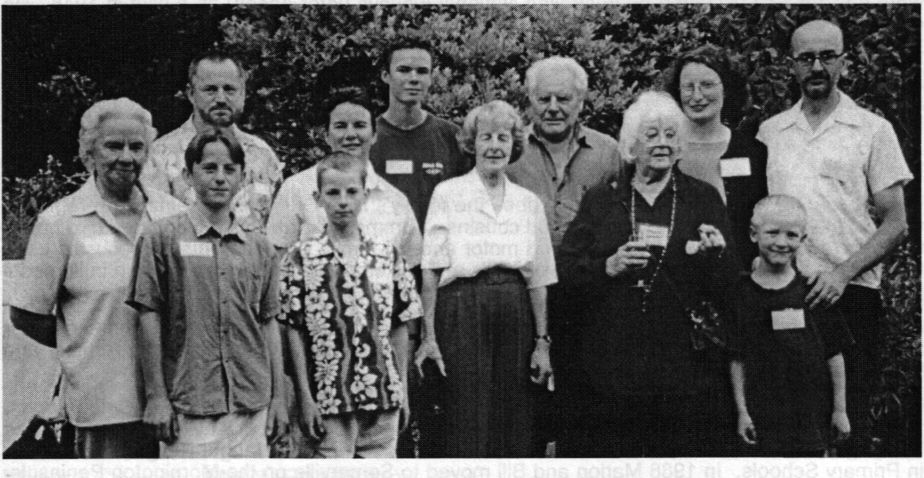

This documentation of the Robertson family history has been very much a joint project, with contributions from people both within and without the family. I thank all of those who have participated. Discovering my relations has been a wonderful experience for me. Searching out documents and records, meeting and getting to know people, listening to the stories they have to tell, looking for common characteristics among family members and the enjoyment of being with a whole new bunch of friends.

The following narrative is an account of what we have discovered. A joint memoir, for which I am no more than the scribe who has written it down. A collection of stories and potted biographies of the many family members I have been able to track down. The descendants and the forebears of Margaret Henderson and Arthur Robertson, who came to Australia with six of their children in the 1860s.

The genealogical charts and the portraits of family members I present, have been put together with the help of written records and from information and stories given to me by a wide variety of people. Not all of our relations have been interested in contributing and that is their choice. Others were full of good intentions but never got around to sending anything. This does mean you will find gaps in both the genealogical charts and the potted biographies. The cut off birth date for the biographies is 1944. Obviously it has not been possible for me to check every date of birth, death and marriage against official registers, so I have had to rely on key members in each section of the family to supply this information. I apologize if there are inaccuracies or omissions in the genealogical charts, or if names are not spelt correctly.

It is highly unlikely that my account of the Robertson Family story will please everyone. Steering a tactful course through the information and stories I have collected, as well as the sensitivity of individuals, has not always been easy. There are those who want an open and frank ‘warts and all’ approach to the family story and are happy to have both the faults and virtues of their close kin included. Others want a sanitized version with none of the nasties written about or even hinted at. I have been surprised in some cases when people have asked me not to publish some seemingly harmless story or piece of information, particularly when this information is well known among other people or is on public record. One person emphasised the need for a factual presentation and then, in the same letter, asked me not to publish certain facts!

These different attitudes illustrate for me one of the things I have found most pleasing about my Robertson relations. They are very human everyday sort of people. Let me assure you I mean this as a compliment. I have not discovered any saints, nor have I found any incorrigible sinners and I would not be doing individuals a service if I presented them as all good or all bad. Whether we like them or not, the people described in this publication are our relations. While recognizing and accepting each other’s faults, we need to look for and celebrate the good that exists in great abundance within our family.

Some people may question the authenticity of the material I present. Where possible I have used official records and documentary evidence to help me sort out the most likely version of events, and in many cases I have asked direct descendants to check what I have written. Sometimes however this has produced contradictions and confusion rather than clarity. So I

page 2

have had to make editorial decisions about what to include and what to leave out. I hope no one will be offended by what I write and will understand if my portraits and version of events differ a little from what they believe to be true.

This version of the Robertson family story is not intended to be a definitive account. I see it more as a starting point for those of you who are interested in learning about your family background. The very publication of my account may produce new information that has not been available to me, prompting people to explore their memories and the cupboards where forgotten letters and family documents are stored. My time and resources have been limited and someone else may be interested in continuing the research I have started. The overseas connections could certainly do with further exploration.

As much as possible, I identify the sources from which stories and information come. In many cases very similar information or stories come from a number of sources, so that what I present is a composite and cannot be attributed to a single individual or record.

In both the genealogical charts and the biographies, I identify women by their maiden names in preference to their married names. This simplifies the identification of family units and fits in with the practice of our Shetland ancestors. Direct quotations are indicated by double quotation marks and in these I use the original spelling and grammar of the writer. Single inverted commas are used for second hand quotations, for emphasis, or for the names of ships, books and so on. Square brackets are used within quotations when I have added words to facilitate clarity and for editorial comments.

The people who have assisted me are too numerous to mention individually, but let me assure you it is your enthusiasm and encouragement that has kept me at my task when I have been tempted to give up. Time now to get on with the story. I hope you will enjoy what I have written.

With kind permission of the Innisfail Advocate

Margaret Worrall

Innisfail, 2002

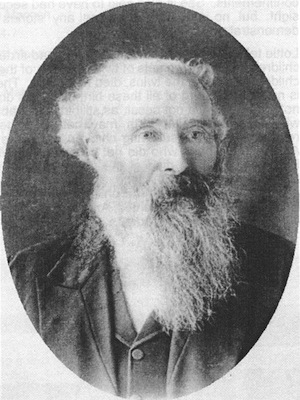

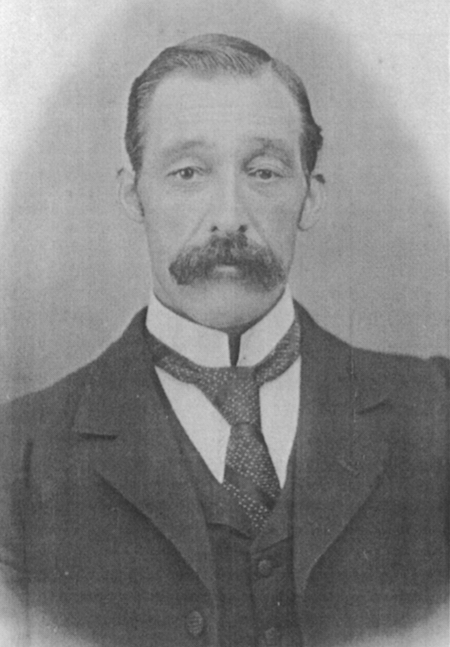

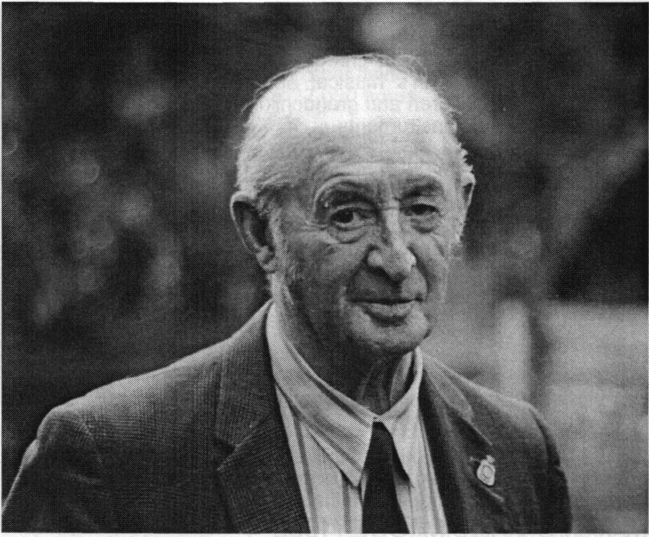

Arthur Robertson was the first of our Shetland ancestors to come to Australia. He was born at Hellister, Whiteness on 3 November 1815. The only things we know about Arthur's father is that his name was James Robertson, he came from Stromness, and he married Barbara Manson of Cova in 1811. James disappears from the records after the birth of his third child in 1817 and as there is no record of his death in Shetland, it is possible he died at sea.

We know more about the family of Barbara Manson. Her parents were Arthur Manson and Martha Thomasdaughter who married on 1 January 1772. Both were born in the 1750s and Arthur Manson’s father was probably a James Manson. Barbara was born in 1782 and had six siblings whose names are listed on the family chart. Magnus Manson, who sailed and perished with Sir John Franklin in the search for the Northwest Passage, is believed to be one of Barbara’s relations. (See notes on the Franklin expedition in Appendix 1.)

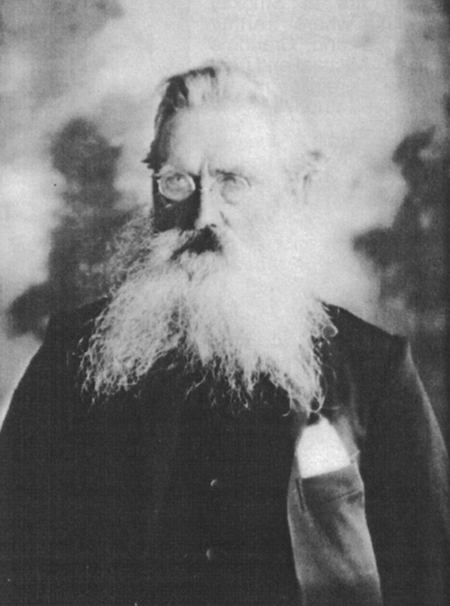

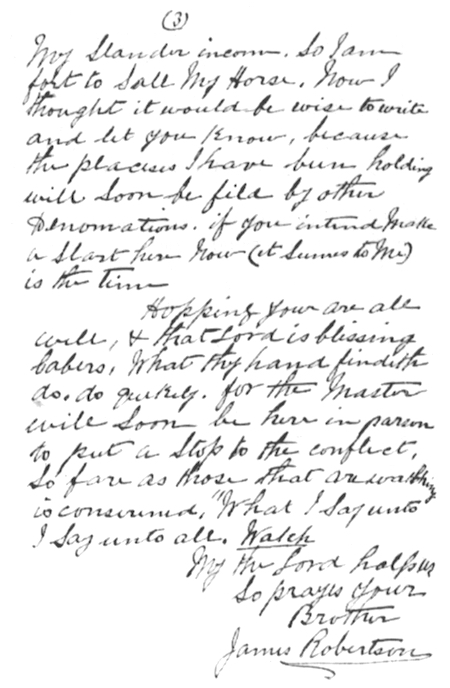

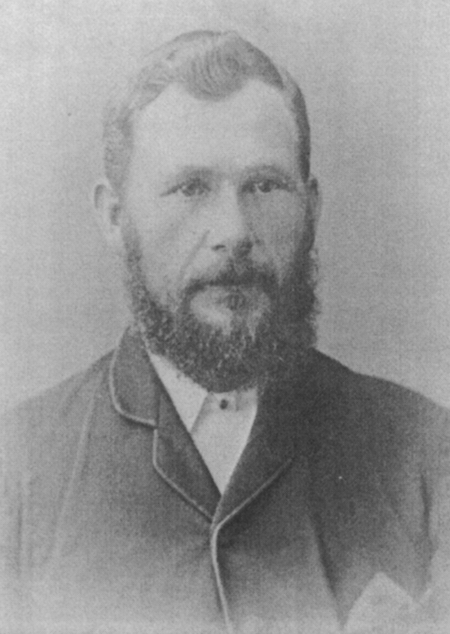

Writing in 1937, son Robert describes Arthur Robertson as follows, “My father was a person of medium height and of well built proportions; a well-shaped head, with grey, curly hair, which we were told was black in his youth. The head sat over a pair of ample shoulders. His blue eyes were large and expressive as they looked out at you from beneath a broad forehead. His voice was of the bass register, melodious and pleasing in its cadences. Ready of speech, epigrammatic of phrase, he was an interesting conversationalist. He wore a long flowing beard, which added a touch of patriarchal grace to his general characteristics. By trade he was a stone mason, and by profession he was a teacher of music and singing. 1

Arthur had a variety of skills. He was seaman, a farmer and fisherman, a mason and a stone waller. He played the violin and taught music. Arthur’s marriage to Margaret Henderson on 15 August 1837, is recorded in the Tingwall register. The service was conducted by the Rev J Turnbull.

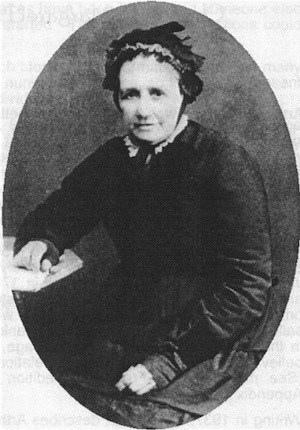

Margaret Henderson was born on 4 September 1812, at Burwick, Shetland, the daughter of Peter Henderson and Agnes Williamson, who had been married on 12 August 1798. All we know about either parent is that Peter is described as a fisherman of Burwick. Margaret had two older brothers, Walter and William and an older sister called Elizabeth. Elizabeth died at the age of fifty-two, unmarried and without issue. The boys lived to the ages of eighty-two and seventy- three, were married and had families.

page 4

Robert does not describe his mother’s physical appearance but tells us, “Mother was a homemaker. Had she followed a business career she would have made a success of it. Her home was a comfortable place to be in — just homely. She dispensed hospitality graciously to all comers”. Also this loving tribute, “A boy born into a poor home sees more of his mother than a boy born into a rich home sees of his. The poor boy’s mother is his nurse, governess, tutor, college professor, and his all, in one personality, the cords of filial love binding all together, giving a real oneness to the home." 2

Great granddaughter Margaret Haine gained the impression from her mother and her uncles, that Margaret Henderson was a gentle loving person. 3 Lottie Dickins, my mother and Margaret Henderson’s granddaughter, was told that Margaret Henderson's brothers were both left handed, stuttered and were travelling preachers in Shetland. 4 Lottie’s father, Robert, told her he had a lawyer cousin called Henderson living in NZ and Margaret Haine believes there are Henderson relations in Canada. Margaret Henderson had birthing skills and was called on to attend confinements. She is also said to have had second sight, but no one has given me any stories to demonstrate this.

Great granddaughter Margaret Haine gained the impression from her mother and her uncles, that Margaret Henderson was a gentle loving person. 3 Lottie Dickins, my mother and Margaret Henderson’s granddaughter, was told that Margaret Henderson's brothers were both left handed, stuttered and were travelling preachers in Shetland. 4 Lottie’s father, Robert, told her he had a lawyer cousin called Henderson living in NZ and Margaret Haine believes there are Henderson relations in Canada. Margaret Henderson had birthing skills and was called on to attend confinements. She is also said to have had second sight, but no one has given me any stories to demonstrate this.

Lottie tells us that Margaret Henderson had sixteen children including two sets of twins. Seven of these children, including the twins, died as babies. There is no official record of all these births but this does not mean they did not occur, as stillbirths or babies who died soon after birth may not have been registered. Of the surviving children, six came to Australia. Of those who did not come to Australia, Barbara Robertson died at the age of twenty-two before the family left Shetland, and the fate of John and Peter is uncertain. The children who came to Australia were Agnes, James, Arthur Jnr, Margaret Jnr, Robert and William Adie.

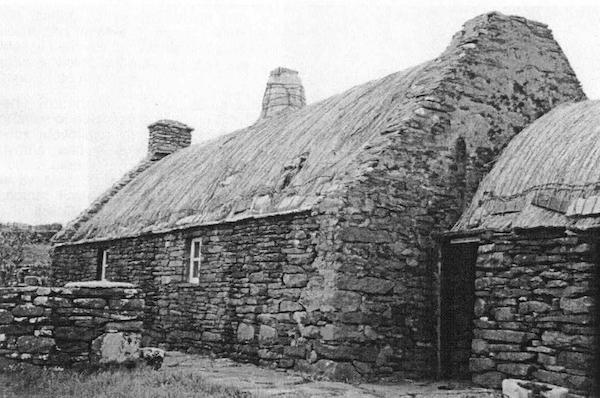

A Shetland Farm

An isolated farm at Aith Voe with fine stone walls of the type the Robertsons would erect in Victoria.

1 R. Robertson, The Port Campbell Revival, p.47

2 R. Robertson, The Port Campbell Revival, p.53 and p.50 respectively

3 Interview with Margaret Haine, April 2000

4 information from Lottie Dickins recorded by her daughters Marie Nemec and Margaret Worrall

page 5

page 6

Arthur Robertson travelled to Australia on the Vanguard, a ship of 1303 tons carrying 232 passengers (47 Scots, 82 English and 97 Irish), which sailed from Liverpool on 21 July 1863 and arrived in Melbourne on 1 November. Arthur disembarked at Geelong. He is listed in the ship’s manifest as ‘labourer’, but it is understood in the family that he worked his passage as a leading hand.

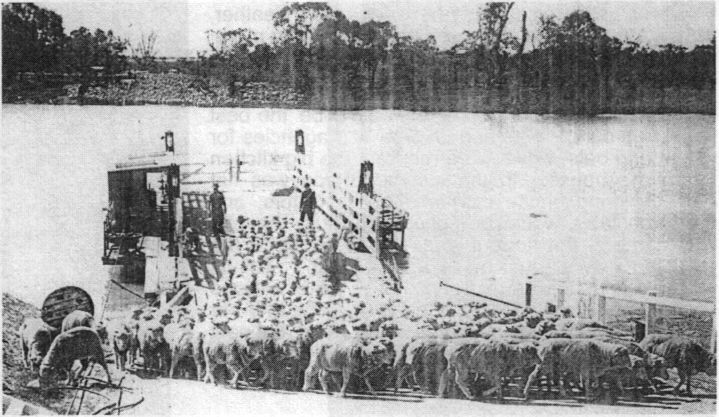

John Collins McCue tells us that when the Vanguard docked at Geelong it was met by John Lang Currie. Currie was the owner of Larra station in Victoria’s western district. He was looking for workers for his farm and as Arthur had experience with sheep in Shetland he was taken on. The trip to Larra was made on foot, walking beside a wagonload of supplies pulled by Shire and Clydesdale horses. John McCue describes Arthur’s first encounter with a kangaroo, “There were no fences between Geelong and their destination, only ‘corner cairns’ of piled stones to mark the limits of various ‘runs’. Being in the wilds and uninhibited as were most of his people - he went into the bushes. Choosing unwittingly the established ‘squat’ of an old man kangaroo. Both fled in terror at this novel encounter. The kangaroo in huge bounds, the immigrant in hobbled haste, his ‘breeks aground’. His dignity shattered, he skinned his knees on the ‘pebbled sward’ as he clawed his way back to the wagon and the squatter.“ 1

James was the first family member to join Arthur in Australia. Arriving in Sydney in 1865, he came overland to join his father in Victoria. James’ grandson, Neil Saunders, wrote in 1975, that James worked his passage, leaving his ship with an honourable discharge. 2 Neil had seen the discharge papers but did not know their current whereabouts. Neil's sister, Margaret Haine, says James walked from Sydney to Melbourne accompanied by a friend. They had little money and people they met along the way helped them by giving them food. One of the problems James encountered was understanding the English spoken by the people he met and no doubt they had trouble understanding his Shetland dialect! 3

Margaret Henderson was the next to arrive, accompanied by the two youngest children, Robert and William Adie. They sailed on the Chariot of Fame out of Liverpool on 29 June 1866 and arrived in Victoria on 22 September. In the shipping record their ages are stated as forty-five, eleven and seven respectively. Margaret was in fact fifty-four years old at the time of her arrival, Robert had turned thirteen, and William was eight. The Chariot of Fame of 1639 tons, carried 278 passengers - 31 English, 25 Scottish, and 242 Irish. There are two interesting points about entries in the passenger list of the Chariot of Fame. Firstly Agnes, Margaret Jnr and Arthur Jnr were booked to travel on the same ship with their mother. For some reason they did not do so and their names have been crossed off the list. The family were paying passengers and possibly there was not enough money at that stage to pay for the three extra fares.

Sailing Ship. Miriam Robertson Lawson, the daughter of James Robertson, included this postcard in her album This may be the type of vessel on which the Robertsons travelled to Australia in the 1860s. >

Sailing Ship. Miriam Robertson Lawson, the daughter of James Robertson, included this postcard in her album This may be the type of vessel on which the Robertsons travelled to Australia in the 1860s. >

page 8

Secondly, listed with the rest of the family is Ann Robertson, widow, 23 years. Who was Ann Robertson and what happened to her? The passengers’ surnames are not listed alphabetically and the seven Robertsons appear as a group. John Collins McCue was told that John Robertson Jnr and his wife had intended to join the rest of the family in Australia and the reason Agnes, Margaret and Arthur, did not sail with their mother in 1865, was that they were waiting for John. Is it possible that Ann Robertson was his widow? However if the Ann Robertson, who sailed with Margaret Henderson was in fact John’s wife, they would have already known of John’s death, because Ann was listed as ‘widow’. All these questions must be left unanswered until and unless we obtain more information about the mysterious Ann Robertson.

When their father had saved enough money, Agnes, Margaret Jnr and Arthur Jnr were sent for. It is understood that Arthur Jnr worked his passage. They sailed from Plymouth on 2 July 1867 aboard the John Temperly, 998 tons, carrying 356 passengers, Master - J W Tucker. The ship arrived in Melbourne on 26 September. The two girls are described as knitters and Arthur as farmer. Travelling on the same ship were a number of single women including Mary F Halls, age 18, ‘servant’. Mary Halls would later marry James Robertson.

When their father had saved enough money, Agnes, Margaret Jnr and Arthur Jnr were sent for. It is understood that Arthur Jnr worked his passage. They sailed from Plymouth on 2 July 1867 aboard the John Temperly, 998 tons, carrying 356 passengers, Master - J W Tucker. The ship arrived in Melbourne on 26 September. The two girls are described as knitters and Arthur as farmer. Travelling on the same ship were a number of single women including Mary F Halls, age 18, ‘servant’. Mary Halls would later marry James Robertson.

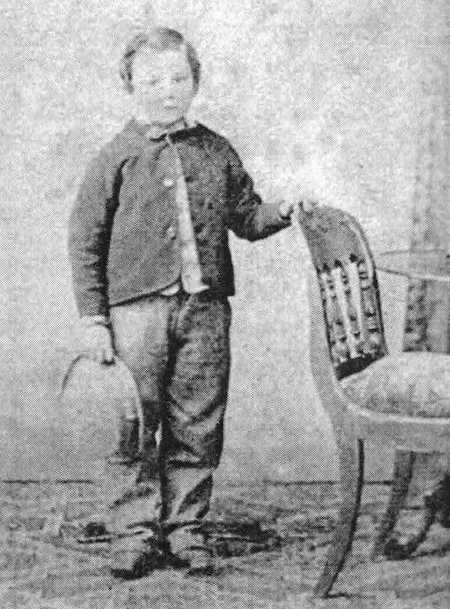

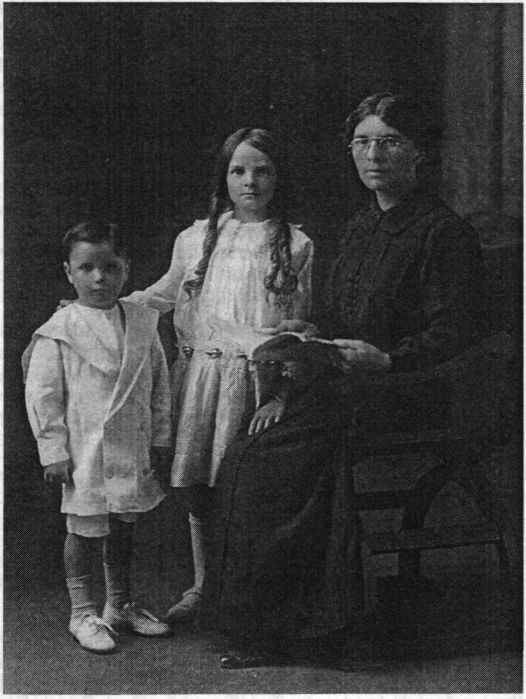

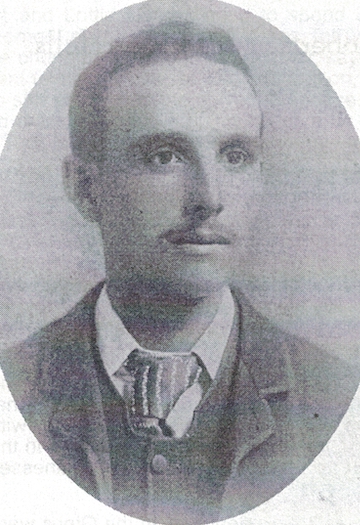

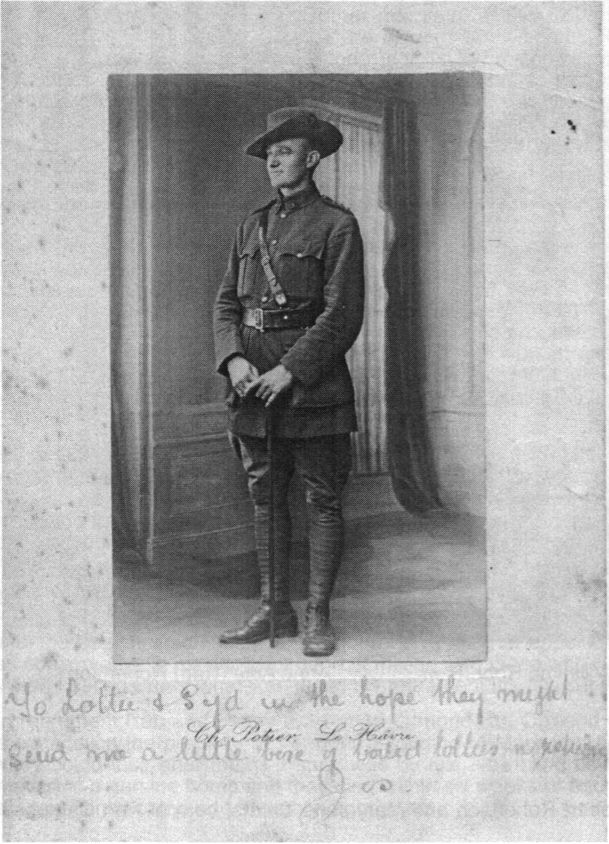

William Adie Robertson about the time the family migrated to Australia >

1 Notes written by John Collins McCue supplied by his daughter Helen Krigsman

2 Letter from Neil Saunders to John Collins McCue, 12 June 1975

3 interview with Margaret Haine. April 2000

How was it this family of Robertsons came to Australia? Who were they and what do we know about their origins? Why did they leave Shetland?

page 9

page 10

Robertson means son of Robert, and it is a common name in Shetland as well as in mainland Scotland. There is not necessarily any connection between Shetland and Scots Robertsons, although there is a tradition in our family that our Robertson line moved to Shetland from Scotland at some time unknown, because of religious persecution. I have no concrete evidence to support this. Indeed it would seem the Shetland line of our heritage is more Norse than Scots, and Marjorie Mathieson told me that her great grandfather Arthur Robertson, the first one to come to Australia, was often heard to say, ‘Achl The dirty Scot, we’re Norse’ - suggesting he saw himself as having Scandinavian rather than Scottish affiliation. Both Manson and Henderson are Norse names, Manson being a derivative of Magnus, and Agnes Williamson, according to Robert Robertson, was of Swedish extraction.

The standardization of surnames did not become common practice in Shetland until late in the 18th century. Prior to this the use of patronymics by the locals means it can be hard to trace lineage. We not only have the use of the suffix son, as in Robertson — son of Robert, and Henderson - son of Henry, but names such as Thomasdaughter — daughter of Thomas. William the son of Robert would be known as William Robertson but if William had a son called Thomas, he would be known as Thomas Williamson and so on. Women continued to use their own name after marriage and this is how they appear in the records until late in the 19th century. Following this custom, I always refer to Arthur Robertson's wife as Margaret Henderson.

While I was in Shetland, I was told that the traditional practice in naming children was to call the first son after the paternal grandfather and the second son after the maternal grandfather. The first daughter was named after the maternal grandmother and the second daughter after the paternal grandmother. The naming of later children was less regulated. This rule for naming children was not always applied, but it can give a clue to family connections and lineage.

The first definite record of our Robertsons in the Tingwall/Weisdale/Whiteness and Hellister area that the Shetland Family History Society (SFHS) and I have so far been able to locate, is James Robertson of Stromness, Whiteness, who married Barbara Manson of Cova, Weisdale on 26 December 1811. 1 They called their first-born child John (born 1812), which may indicate that Arthur’s father was called John. This is perhaps supported by the fact that when the first- born child died, a third son was also given the name John. The second child was Arthur (after Barbara’s father) and this is the one from whom the Australian line is descended. There were no more children of the marriage and James Robertson disappears from the records, possibly drowned at sea as so many Shetland men were.

Members of the SFHS have suggested that James Robertson may have been an ‘incomer’. But whether he was an incomer from Scotland or from another part of Shetland we do not know. Efforts to establish a relationship with other Robertson families in Shetland have been unsuccessful. We share given names such as Agnes, James, John and Robert with other Robertson families, but these were popular names in many families who have different family names. There seem to be dozens ofAgnes Robertsons and one is recorded in the Tingwall area in 1785. Was she related? A James Robertson of Moustoft, with a family of five, is listed in the 1804 Weisdale records for food relief. Was he related? And Thelma Watt of the SFHS has found the record of a John Robertson of Stromness who married a Philadelphia Tait in 1816. They had sons called John and Arthur and a daughter Margaret. The similarity of age, location and names suggests to me that James and John may have been brothers but this cannot be substantiated from the limited records available.

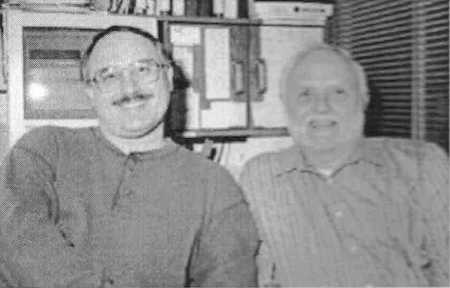

Our Arthur’s younger brother, John Robertson, was a shopkeeper. He lived all his life in Shetland but some of his descendants emigrated to Australia, Canada and the USA. I have quite extensive details about John’s family and their descendants and I have made contact with two of John’s descendant in the USA - great grandson, David Gunn and his nephew Roger Douthitt. I have not been able to trace any of the John’s descendants in Australia. There do not appear to be any direct descendants of either Arthur or John still living in Shetland.

I have not been able to trace any of the John’s descendants in Australia. There do not appear to be any direct descendants of either Arthur or John still living in Shetland.

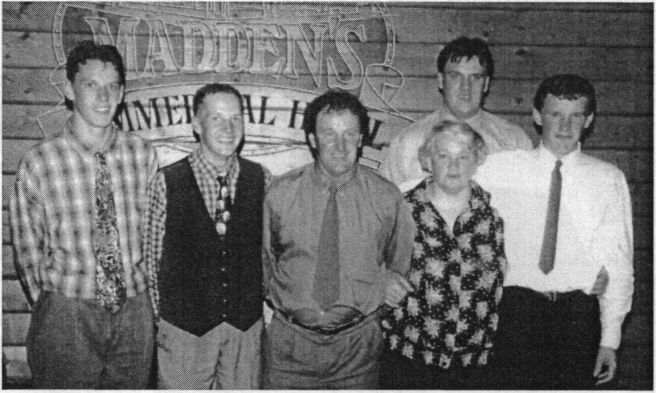

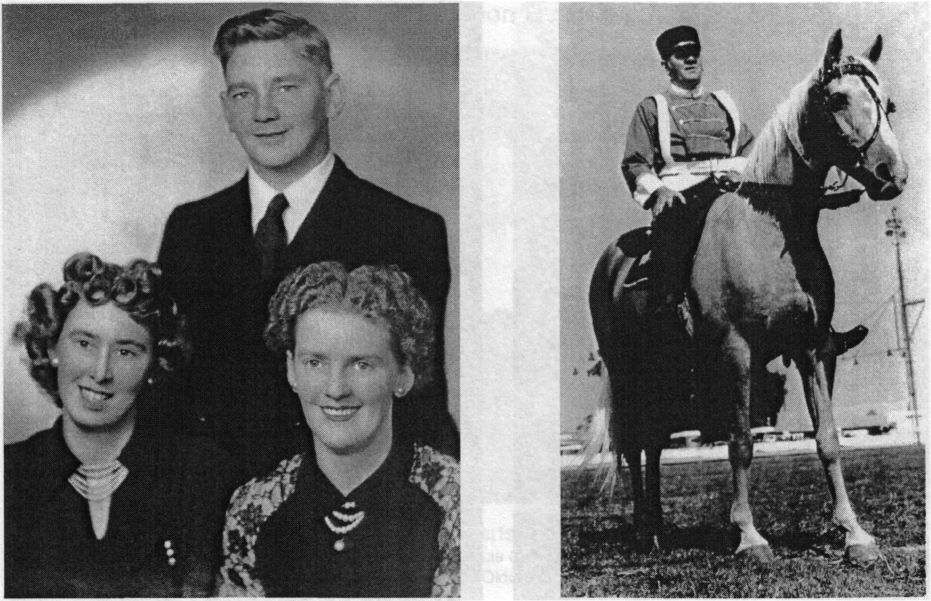

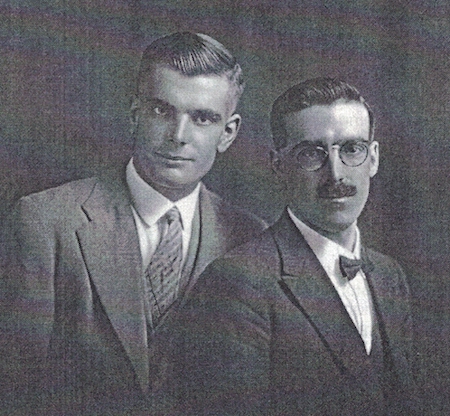

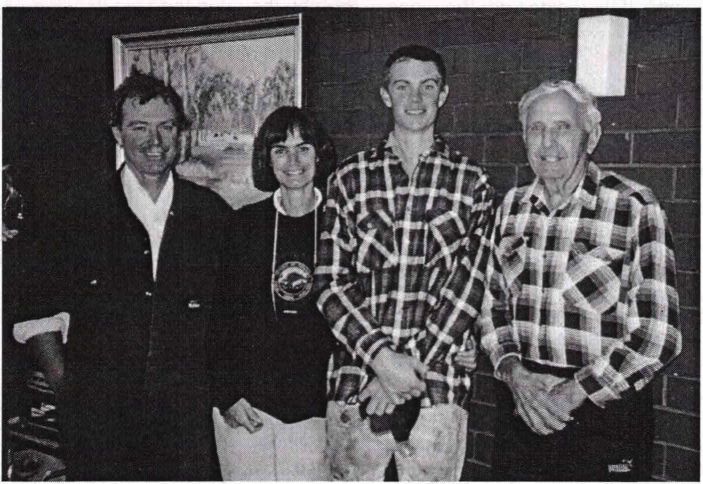

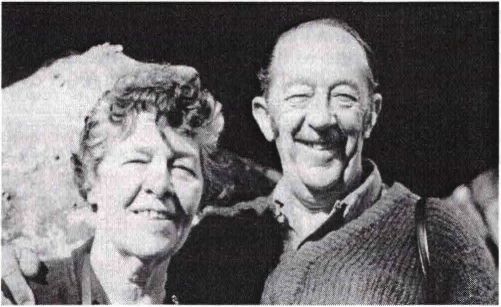

American relations, Roger Douthitt and David Gunn >

page 11

There are a number of books available which describe the history and traditional life of Shetland much better than l can do and any of you who have visited Shetland, and the museums there, will be aware of the difficult life our ancestors lived. 2 A harsh climate. High rates of child mortality. Menfolk lost at sea. Periods of famine when crops failed. 3 Oppressive lairds/landlords. Bureaucrats and clergy imported from Scotland intent on imposing Scottish ways of doing things. 4 And a political system that supported the landowners against their tenants. Before the 19th century when roads were built, transport in Shetland was by foot or by boat around the coastline. Individuals stayed very much within their own communities and communities were contained within a particular geographical area. Marriage options were generally limited to those living within those areas.

The reading l have done suggests that the inhabitants of Shetland and Orkney, along with the Highlanders of Scotland, were regarded by the English and Lowland Scots as an inferior race who were uncouth, ignorant and incapable of making the best use of the land they farmed. How similar this sounds to the attitude some of our forebears held and some people still hold with regard to the Aborigines who were displaced by white settlement in Australia.

The Highland clearances, when landlords demanded greater returns from their properties and replaced crofters and tenant farmers with sheep, occurred a little later in Shetland than elsewhere throughout the British isles. The main effect was felt in the 1850s and 1860s when hundreds of Shetlanders emigrated to Australia, New Zealand and Canada. There were programs for assisted emigration and Norah Kendall outlines some of these in her book With Naught but Kin Behind Them. Looking through the records of the Tingwall Sheriff Court Processes for the 1850s and 1860s, l was struck by the number of ‘orders for removal’ brought by landlords against their tenants. Some were absentee landlords who lived in the cities of England and Scotland. They seem to have had little sympathy for their tenants and described the clearances as ‘improvements’. An early version of economic rationalism?

The Shetland l found on my visit in May 1997, is of course very different to the Shetland of history books. However the wind blows just as it always has and island activities are still

page 12

very much controlled by the seasons and changing weather patterns. The Norse influence is strong and this makes Shetland different to Scotland and England. For me, the most lasting impressions of Shetland involve the colours, the sounds, and the touch of the wind. When I was there, the dominant colours were the blue of sea, lochs and sky, the grey of clouds and stone, and the bright green of new growth in the fields. There are not too many trees in these wind wound islands and there are few places where you are out of the sight of the sea. The sea, the wind and the seabirds are ever present.

The Wind Wound lsle

Wind ruffles the surface of Weisdale Voe.

The registration of births and deaths did not became obligatory in Scotland until 1855, however the first all-Shetland census was held in 1841 and this was followed by further censuses at ten year intervals. These along with other records tell us something about our forebears. Although there is no record of James Robertson’s death, his wife, Barbara Manson, is described in the 1841 census as ‘widow’. The record of her death in 1866 at the age of eighty-four, states she was the ‘widow of James Robertson farmer’. We can assume that James was also a fisherman as farming and fishing were joint activities for crofters and he may have also been a seaman working on British ships that picked up crew in Orkney and Shetland. Barbara Manson’s death was registered by her grandson Arthur Robertson Jnr who signed with a cross. This suggests that Arthur Jnr may not have been able to write at that time.

Margaret Henderson’s father, Peter Henderson, is described in the census records as ‘fisherman’, as is her brother, Walter Henderson.

Arthur (the son of James Robertson and Barbara Manson) is listed at various times as farmer mason, and music teacher. We know from family stories that he was also a seaman. At the time of the 1841 census, he is recorded as being absent from home and the assumption might be made that he was away at sea. The women of the family would have all been involved in farming activities, as it was the women’s responsibility to maintain the farms while the men were away fishing during the summer months. Women were also knitters, and it seems an interest in knitting and other handicraft has come down through the family in Australia.

Arthur’s brother, John Robertson, is described in the census as merchant, grocer and farmer. While in Shetland I was shown the building where he had his shop at Strombridge. At the time of her death in 1881, his wife Joan is described as ‘widow crofter 2 acres’.

Arthur’s sons, James and John, are recorded in the 1861 census as ‘fishermen’. James was a crew member on whaling ships in 1858 and 1859. Whaling ships went out during the summer months to the seas around Iceland and Greenland. Family stories claim John had his own boat

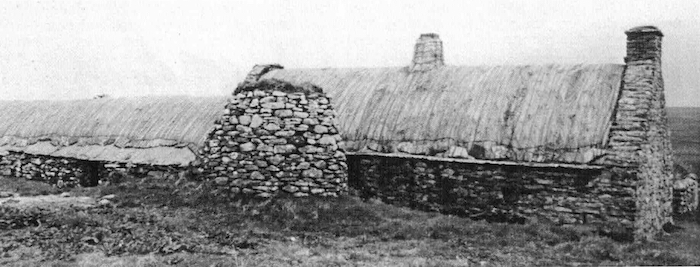

Shetland Croft Museum, Southvoe circa 1870

The roof and the chimney were thatched with layers of turf and straw tied in place with straw ropes. Extra ropes were slung over the roof and weighted with large stones to keep it anchored against the wind. Light came from tiny skylights at eaves level. If and when the croft could afford it proper windows might be installed. The floor was flagstones or packed earth. The dwelling part of the building was divided into two rooms one for living the other for sleeping. The main focus was the hearth where a peat fire for heating and cooking, and for drying fish and meat, burned continuously. Adjacent to the living area, divided from it by a passage, was the byre where feed was stored and a milking cow tethered during the winter. Next to the cottage is the barn with bins for storing bare (barley) and oats and all the farming equipment. There was a hard floor for thrashing, sheep skin platens for sifting and sorting the grain; and a ‘quern’ (a hand turned stone mill) for grinding it. At one end of the barn was the kiln for drying grain; this is the round section slightly detached from the house above.

page 13

was a privateer against the French, and ran guns to America during the Civil War. More about these two later on.

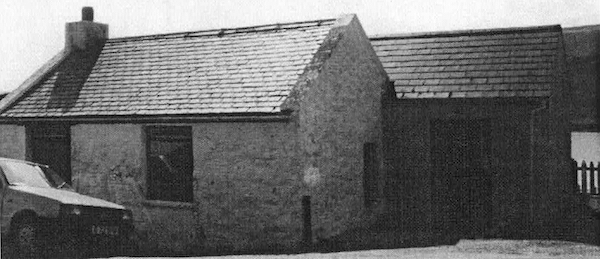

John Robertson's shop, 2000

There have been several additions and alterations to the building.

Stories about the Robertson's life in Shetland have been handed down from one generation to the next. Most of those I relate here were told to my mother Lottie Dickins by her father Robert Robertson, and were recorded by my sister Marie and myself. ln many cases there are similar stories in other sections of the family.

When a whale was sighted, the men would go out in small boats to chase it. Each family represented at the kill got a share of the whale. On one occasion, when a whale ‘blew’, the older Robertson menfolk were away from home. Robert, who would have been about nine years of age at the time, knew that if his family were not represented they would not get a share of the whale. He asked to go in the boat with the men but was told ‘No laddie you're too young’. Robert went to another boat and asked to be taken on board and this time the crew relented and took him with them. Afterwards Margaret Henderson was very angry with Robert, for chasing whales in an open boat was a dangerous business.

Whale oil was used to put on bread or bannocks and when the men went fishing they wrapped their ‘sandwiches’ up and sat on them. The heat from their bodies melted the oil, which then soaked into the bannock. Whale blubber was also used to fuel lamps.

Money could be made by collecting down from birds nests on the cliff faces. Young men or boys were let down on ropes from the top of the cliff. This was another dangerous occupation and men sometimes fell to their death. “The men were either sailors or down collectors and were therefore either drowned, lost at sea, or fell to their death.“

A local superstition said that if you killed a lark you broke a toe; young Robert was a good shot with stones, he killed a lark and sure enough he broke his toe.

Each pupil had to bring peat to school for the fire and if they brought none then that pupil sat furthest from the fire.

Coming home from a trip at sea Arthur Robertson discovered the Laird had fenced off the common land to graze his sheep. This made Arthur so angry he pulled the fence down and knocked the laird down. He was charged with assault and fined. Lottie believed this was the reason the family left Shetland. As my mother told the story, the laird was married to Arthur’s sister and lived in ‘the only two-storey house on the island‘. This is certainly not correct as Arthur did not have a sister and there were many two-storey houses in Shetland at the time. However the laird’s house may have been the only two-storey house at Hellister or Jackville where the Robertsons lived.

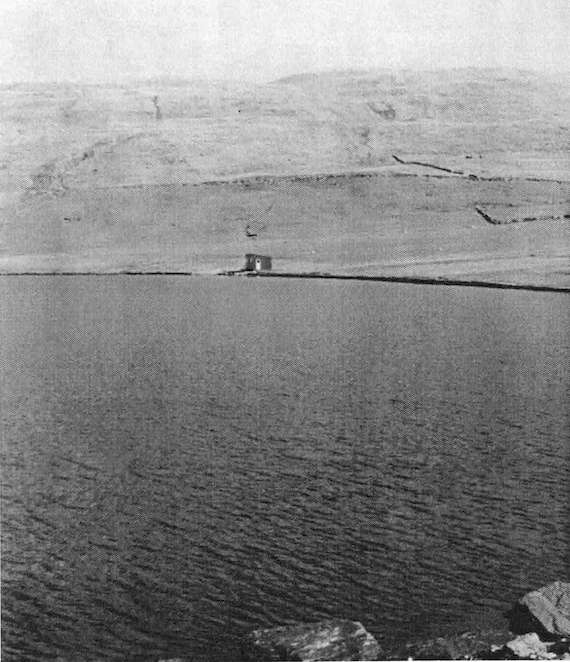

Weisdale Valley and Hellister Loch

View from Weisdale Hill on the western side of the voe.

Hellister Loch

Showing the narrow section of land between the loch and the voe seen in the previous photograph. This is the area where the Robertsons had their croft at the time of the 1841 and 1851 census.

John Collins McCue has a variant of the same story, “Coming home from a whaling trip, Arthur Robertson discovered that his brother-in-law, having been sub-let the whole of the ‘hinterland’ by an English landlord, had enclosed the village within a dry stone wall and was charging rent for what had been common grazing. He knocked down then his brother-in-law and was prosecuted and fined." 6

Thelma Watt and I can find only the most tenuous relationship between the Robertsons and Laurence Calder, who was the family’s landlord at Hellister. John Robertson’s wife was Joan Smith and she had a sister called Philadelphia. The father of Philadelphia Smith's illegitimate son Robert, born in 1856, was Robert Calder, the son of Laurence Calder. Philadelphia obtained a court order against Robert Calder for the payment of “three pounds sterling per annum in name of aliment to an illegitimate male child”. This was to be paid until Robert Jnr reached the age of seven but it seems Robert Calder, who is described as a sailor, avoided his responsibility by taking himself elsewhere. Robert Jnr was recorded in the 1861 census as Robert Smith (4 years) but in 1871 he is recorded as Robert S Calder (15 years). 7

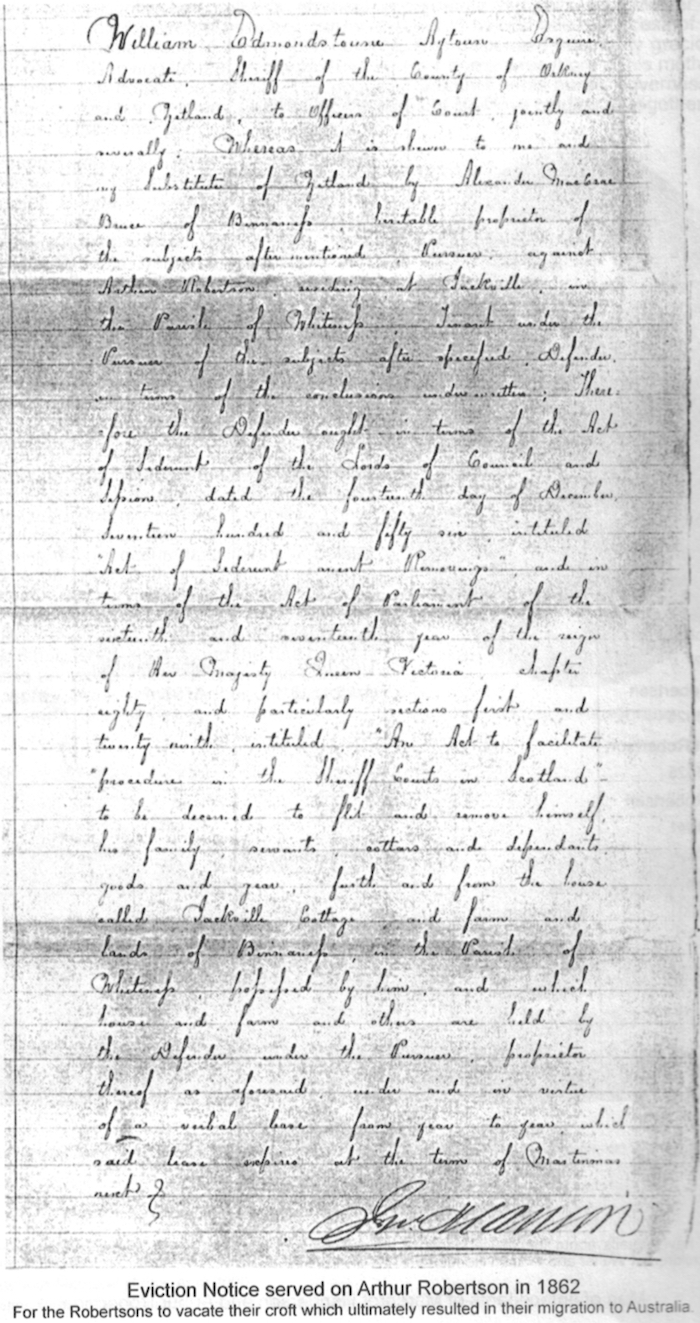

These stories demonstrate the unreliability of tales that are handed down from one generation to the next, becoming exaggerated or changed as they go. They do however give us clues to follow up. I was not able to verify the assault charge but it was while trying to locate a record of the assault case in the Tingwall Sheriff Court Processes that I found two eviction orders taken out against Arthur Robertson. If Arthur Robertson did in fact assault someone this may have well precipitated one of the two evictions.

The first eviction, in April 1858, was from the land at Hellister owned by (or sub-let to?) Laurence Calder. Living there at the time of the 1851 census, Arthur is described as "farmer, 4 acres, employs 2 labourers”. 8 After being evicted from Hellister the family moved to Jackville at the tip of Stromness where, according to the 1861 census, the family had 8 acres. Their landlord was Alexander McCrae Bruce of Binnaness. The family was evicted from this site in October 1862.

Crofts were held “in virtue of a verbal lease from year to year" and the order for removal charged the tenant to “flit and remove himself, his family, servants, cottors and dependents, goods and gear, forth and from the house called Jackville Cottage and farm and others held by the Defender.“ Unable to find Arthur Robertson in person, the first eviction notice was issued to his wife, Margaret Henderson and the second to his daughter.

The argument with the landlord not withstanding, we must assume it was this second eviction that prompted the family's decision to emigrate. Family stories claim that Arthur and Margaret chose Australia on the advice of their eldest son James. There is no record of James visiting Australia before 1865, but he would probably have heard about the country from other seaman with whom he worked. The family’s decision may have been influenced by the visit to Shetland in 1849 of Dr John Dunmore Lang who was a Presbyterian Minister and member of the New South Wales Legislative Council. He preached to large crowds in Stromness and Lerwick encouraging emigration to Australia. Lang was particularly keen to encourage Protestant female emigration as a way of redressing the disproportionate numbers of males and Catholics in Australia. 10

Lady Jane Franklin, who was Vice-President of the Ladies Female Emigration Society of London, was also in Shetland in 1849, hoping to hear news of her husband’s Arctic expedition, (see Appendix 1). There appears to have been some link between Lady Franklin and the Robertson family and we can only speculate whether she may have assisted or encouraged the family's emigration. Where the family resided between the time of their eviction and their departure for Australia we do not know. Nor do we know how and when they travelled to their departure ports of Liverpool and Plymouth. All we can be certain of is that Arthur Jnr was still in Shetland in January 1866 when he registered the death of his grandmother, Barbara Manson.

View across Whiteness to Weisdale Voe

1. I am indebted to Thelma Watt and other members of the Shetland Family History Society for helping me chase up our Shetland connections.

2. See bibliography

3. The potato famine in Ireland and the effect it had on Irish emigration is well known. Less well known is that the same crop failure, caused by the potato blight, affected Scotland and Shetland, where crofters were also reliant on potatoes as a staple food. The years 1846-1849 saw a series of crop failures. J. Nicolson, Traditional Life in Shetland, p.28 tells us that in the 1840s, “to prevent famine the British government, through the Board for the Relief of Highland Destitution began a programme of road building. The workmen being paid in meal." [Seems there is nothing new about work for the dole.)

4. Shetland did not become part of Scotland until 1469 when the King of Denmark pledged Shetland and Orkney as part of his daughter's dowry on her marriage to the future James III of Scotland.

5. From Lottie Dickins

6. Notes written by John Collins McCue supplied by his daughter Helen Krigsman

7. Shetland Archives

8. lbid

9. Extracts from eviction notice dated October 1862, see Chapter 1

10. N. Kendall. With Naught But Kin Behind Them, Chapter 16

page 17

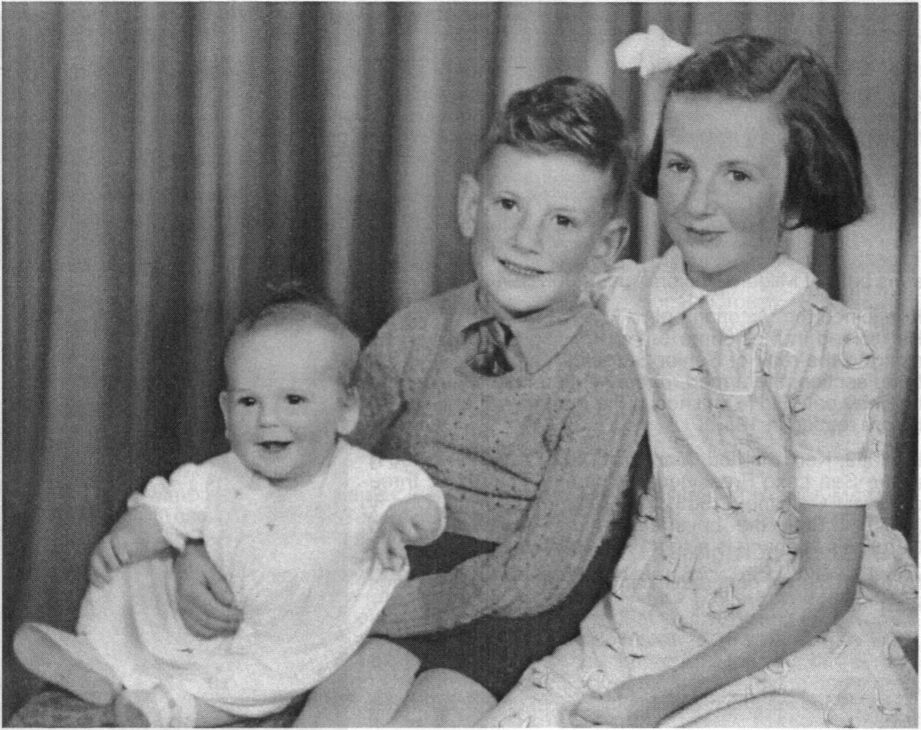

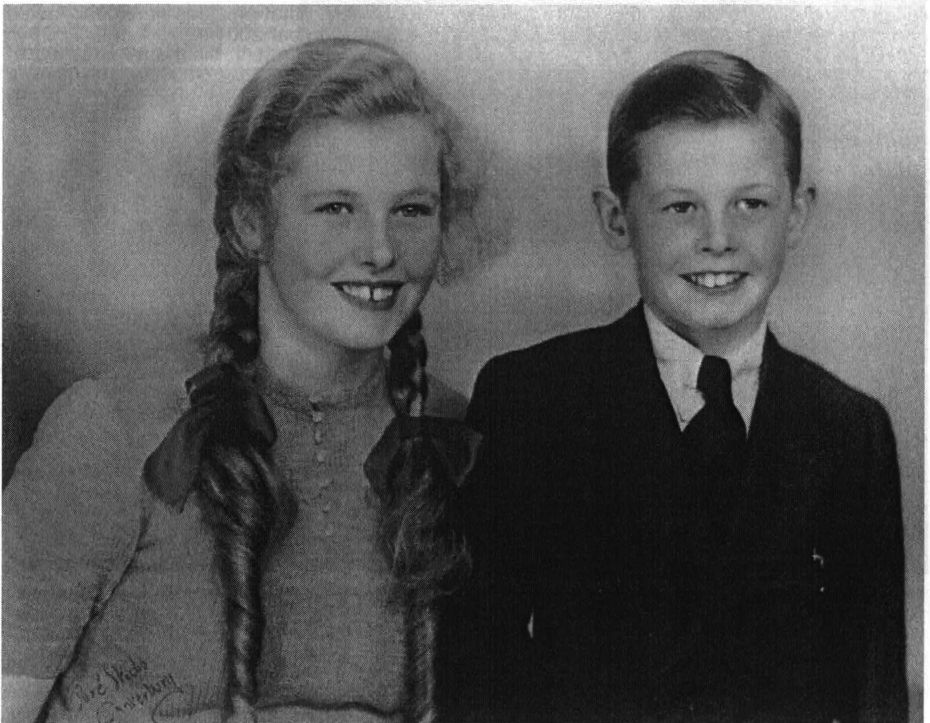

Before moving on to the Australian part of our story, I am going to tell you the little I know about Barbara, John and Peter, the three Robertson siblings who did not come to Australia.

BARBARA ROBERTSON (1839-1862)

Born either at Scalloway on 30 November 1839 (Shetland Records) or at Hellister on 12 December 1839 (Parochial register held in Edinburgh), the second child of Arthur Robertson and Margaret Henderson. 1 She would have been named after her paternal grandmother Barbara Manson, as was the custom with the second daughter.

Born either at Scalloway on 30 November 1839 (Shetland Records) or at Hellister on 12 December 1839 (Parochial register held in Edinburgh), the second child of Arthur Robertson and Margaret Henderson. 1 She would have been named after her paternal grandmother Barbara Manson, as was the custom with the second daughter.

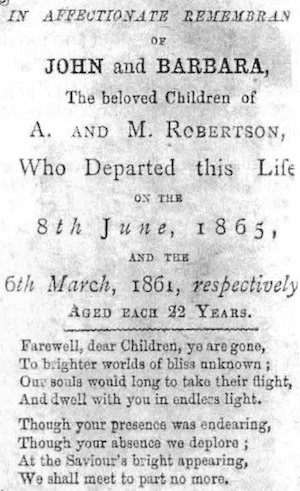

We know very little about Barbara. At the time of the 1861 census, she was living with her Uncle John Robertson at Strombridge and died there on 26 February 1862 (SR). Her death was registered by her brother John. A remembrance notice for Barbara and her brother John incorrectly gives the date of her death as 6 March 1861. l have a photocopy of this notice, which is from an unidentified newspaper; it is undated.

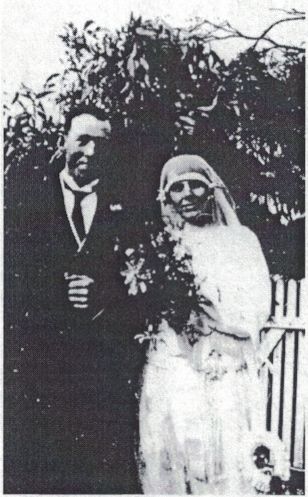

Remembrance notice for John and Barbara Robertson >

Tradition says Barbara died of tuberculosis (TB), a common ailment in cold damp Shetland. In one of the tracts called 'My Grandmother's Prayer' by Frances Saunders, the following is written:

Her passing was uncommonly triumphant. “Oh look” she exclaimed with her latest breath, “I see Jesus, He has come to take me home. No doubts were entertained as to her eternal Safety. 2

JOHN ROBERTSON (1843-1865)

Born at Hellister, Shetland, on 28 September 1843, the second son and fourth child of Arthur Robertson and Margaret Henderson. Recorded as being at Jackville in the 1861 census.

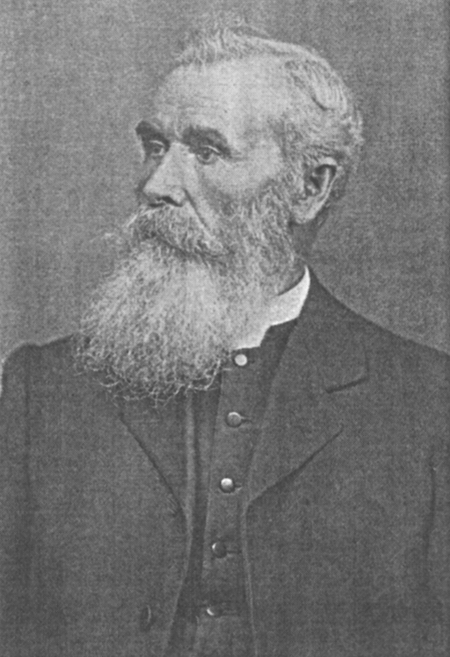

Stories about John and his exploits have come down through several sections of the family. John Collins McCue wrote in 1993:

page 18

John was the fourth child and second son, whose wife was the daughter of Adie. John led a rumbunctious life - was wealthy before he was 20 - mainly from pirating against French smugglers? He took his turn ‘on the whalers’ and normal fishing. When the American civil war erupted he turned his skills to gun running to support the English cause. He ran the blockade of Boston Harbour and was captured and sent back to England twice ‘in irons’. He ventured a third run and was captured again. This time he succum[b]ed to Pneumonia and TB. He had a premonition and left his violin with Agnes [his sister]. A member of the clan has it. I hold a death notice placed in a local paper [in Australia] - a joint notice of the death of Barbara and John with the date of their passing.

This is the same notice l have a copy of, and gives John’s date of death as 8 June 1865. I have not been able to verify John’s date or place of death and wonder if, like the date of death given for Barbara in the obituary, the date of death for John could also be incorrect.

Lottie Dickins said, “John had a boat of his own and went pirating off the Scottish and English coast against the French. Made money and had an honourable pardon by the [British] government.“ Yet another story tells us he was imprisoned in America and he may have died there. Lottie understood John had married a woman called Adie, adding that she too died of TB, and there were no children.

Adie was Arthur Robertson’s shipmate and bosom pal. John Collins McCue again:

Adie in fact, was a robust energetic wharfside brawler - the life-long friend and partner of G[reat] Grandfather Robertson. He was a member of the Tynvald [Tingwall] - the area where the R’s lived - farmed - fished and crofted. Part of their circuit took in the port of Archangel [in Russia]. Here we will pull down the blind. Coming home they discovered that the ‘lessee'[?] had fenced off the hinterland which cut off their oat fields. etc. G was so incensed that he “socked” him down. This operation entailed [?] the socks were pulled off, a rock the size of a big man’s hand inserted and swung with access to the farewell of activity [?]. For this assault GF was fined. He decided to emigrate. Adie vanished to other climates. His name occurs 7/8 times in the family out here [i.e.: Australia]. 6

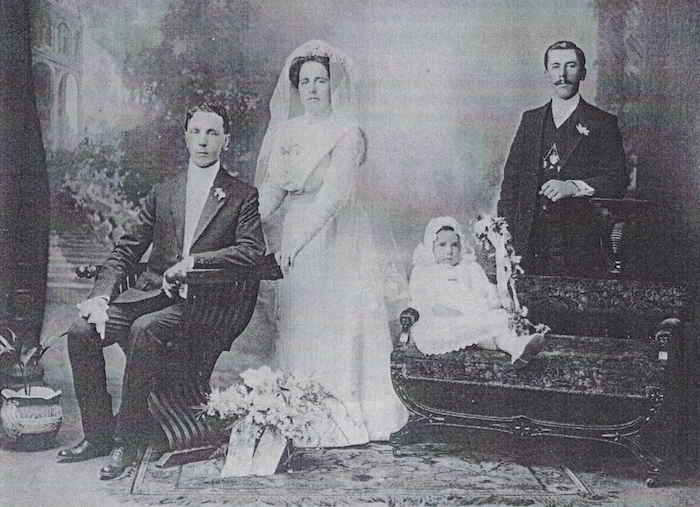

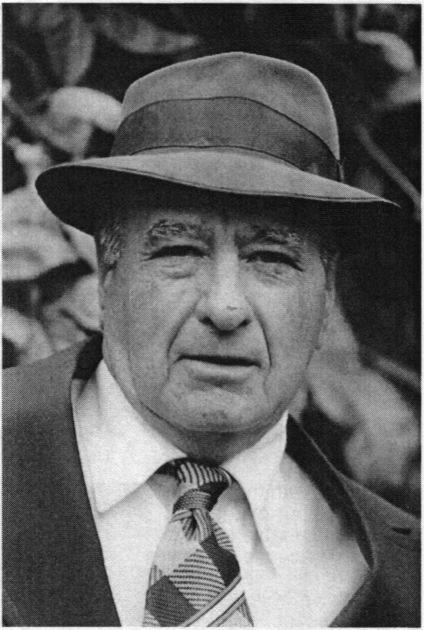

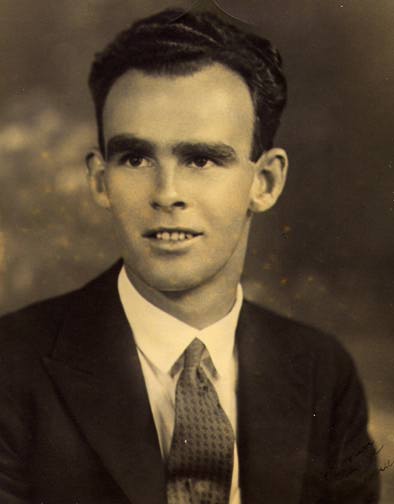

John Robertson >

Some credibility for this story comes from the fact that Arthur Robertson’s youngest son was named William Adie Robertson. William was the only child to get a second name and there is no earlier use of the name Adie in the family as far as l have been able to discover. in generations after William Adie, the name Adie was used exclusively for females. In Shetland, Adie, which is derived from Adam, can be either a family name or a given name and we do not know which it was in this case. The SFHS and I have searched the records to confirm a connection with the

page 19

Adie family but so far none has been found. The best we have come up with in the right time period is a William Adie, merchant of Delting, son of Thomas Adie. This fits in with Margaret and Arthur’s youngest son being named William Adie, but it is only surmise at this stage.

John McCue writes that John and his wife intended to join the rest of the family in Australia but died before he could do so. And John’s violin? Because Agnes did not play she is said to have handed it on to their younger brother Arthur.

PETER ROBERTSON (1845-?)

Born Hellister, Shetland, 15 December 1845, the third son and fifth surviving child of Arthur Robertson and Margaret Henderson. Recorded as being at Jackville in the 1861 census. After this Peter’s life is a mystery. He may have moved to the Scottish mainland according to both Lottie Dickins and John McCue, ‘apprenticed to a baker. His wife - no children - went back to her people when he died quite young’. 7

On the other hand Marjorie Mathieson tells me that when she was first married, neighbours of hers who came from Shetland (probably in the early 1900s), told her that Peter Robertson was the baker and ran the Post Office in Lerwick at the time these neighbours left Lerwick. And another relation, Rob Robertson, has provided the approximate date of death for Peter as being 1925. However Thelma Watt of the SFHS has not been able to find any trace of Peter in the Shetland records after 1861.

Peter's whereabouts must have been unknown to his siblings, as Gertie Grace remembers her grandmother Agnes ‘wishing she knew where Peter was’?

Shetland Croft Museum

See Chapter 3 for details.

page 20

View of the Shetland Coastline at Eshaness, Noflhmaven

Hellister Loch

Near the site of the Robertson croft. Note the fine stone walls.

1. l have tried to check this discrepancy in dates, which occur for several family members. lt seems it is not unusual for there to be different dates in different records. The later date may be a baptismal date.

2. Frances Saunders is the daughter of James Robertson and there are two tracts with the title ‘My Grandmother's Prayer’.

3. J. Nicolson, ‘Traditional Life ln Shetland’, Chapter 2 tells us that smuggling was common during the 19th century. Another way of supplementing provisions and income was salvaging wrecks on the coastline.

4. Letter from John Collins McCue to Mac Dickins, 1993

5. information from Lottie Dickins recorded by her daughters Marie Nemec and Margaret Worrall

6. Letter from John Collins McCue to Mac Dickins, 1993. John’s writing is sometimes hard to decipher. hence the question marks.

7. From Lottie Dickins

8. Interview with Gertie Grace, April 2000

There are several themes that keep reappearing in the lives of Robertson descendants in Australia. These include music, handicrafts, religion and alcohol. l explore these themes as interludes between other sections.

Music, singing and dancing were an important social activity during the long dark Shetland winter, even though the Calvinist ministers who came from Scotland sometimes frowned on such frivolity. The most important instrument was the fiddle, with the gue - a two stringed fiddle of Norse origin - replaced by the modern violin in the 18th century. Greenland whalers carried at least one fiddler to entertain the crew on their long voyages away from home. 1

We know, that as well as being a seaman and a crofter, Arthur Robertson was a musician and teacher of music. Marjorie Mathieson believes the Wards had custody of Arthur's violin, but whether it is still in existence, I do not know.

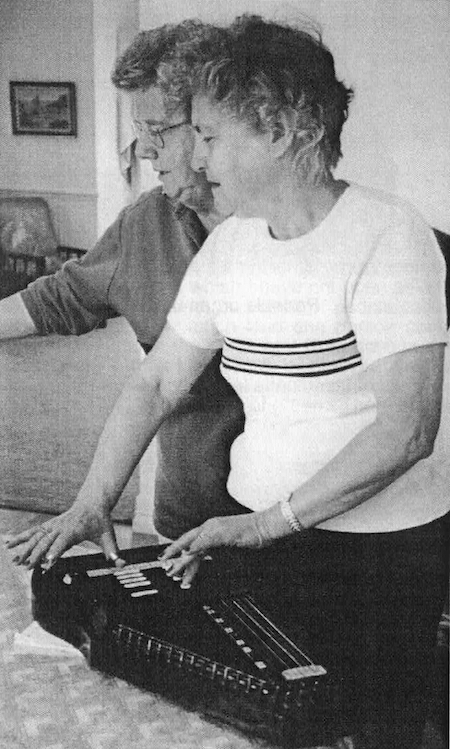

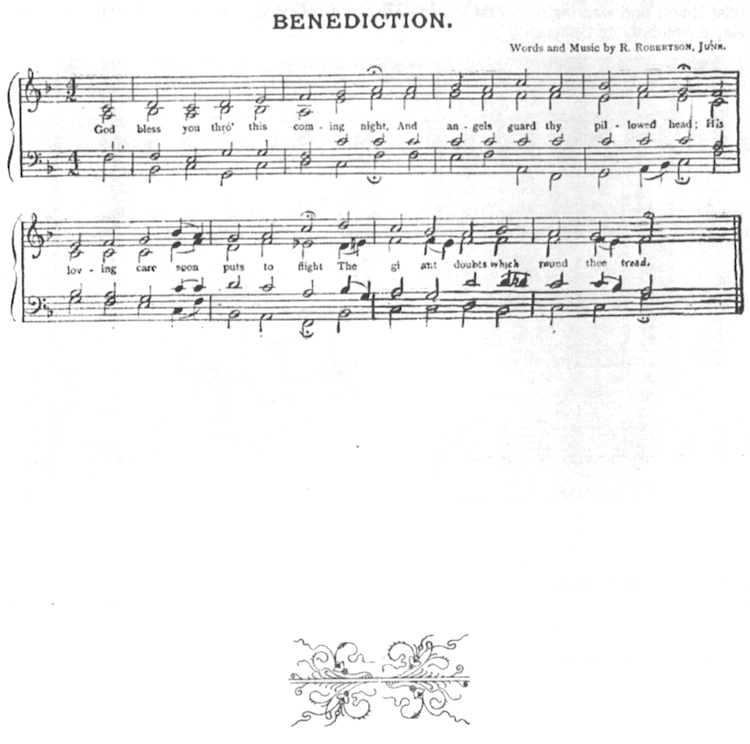

Robert Robertson writes about the importance of music as part of the family’s religious devotions and I have copies of hymns and poetry written by him and other members of the family. One piece by Neil Saunders is dedicated to his mother Frances, “for her ministry of song in the General Hospital, Brisbane". (See Appendix 5.) Her father, James Robertson, gave Frances an autoharp on her eighteenth birthday in 1894. As a married woman living in Queensland she would play this to patients at the Brisbane General Hospital. One of Frances’ grand daughters has become a music therapist.

Music keeps being mentioned in the information and stories coming back to me from different sections of the family. My own mother had a fine contralto voice and sang at social and charity functions, and my Uncle Arthur’s singing of ‘The Mountains of Mourne’ has stayed with me from childhood. It was intended that my brother Neil would learn the violin. Being left handed, Neil insisted he should be allowed to use the bow in his left hand. Between lessons, he re-strung the violin accordingly. The teacher was not impressed and Neil's violin lessons did not continue for very long.

Music keeps being mentioned in the information and stories coming back to me from different sections of the family. My own mother had a fine contralto voice and sang at social and charity functions, and my Uncle Arthur’s singing of ‘The Mountains of Mourne’ has stayed with me from childhood. It was intended that my brother Neil would learn the violin. Being left handed, Neil insisted he should be allowed to use the bow in his left hand. Between lessons, he re-strung the violin accordingly. The teacher was not impressed and Neil's violin lessons did not continue for very long.

Rheita Mott’s Autoharp >

See Chapter 14. The player is Margaret Powell and her sister Dot Geary looks on.

There are many musicians in the family - singers and instrumentalists, professionals, amateurs and teachers of music. The gift of music carries right through to younger generations. When l am aware of the musical skills of individuals, I mention these in the potted biographies. l have been given copies of hymns and poetry written by family members and some of these are included in Appendix 5.

Of course not all the Robertson's descendants are musical. Rutherford Robertson told me that although his father could sit down at a piano and play almost anything asked of him, Rutherford did not inherit his ability. Peter Hogan, an uncle on his mother’s side, would try to get Rutherford to imitate his singing - ‘Up laddie, up the scale’. Uncle Peter’s efforts were doomed to failure. 2

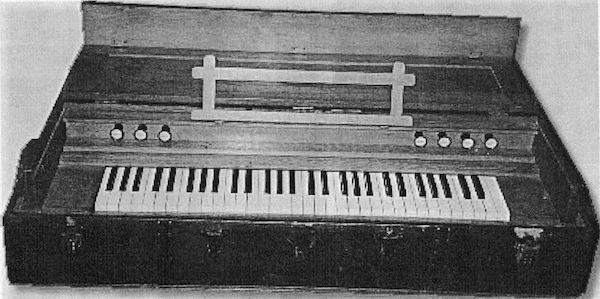

Portable organ used for the tent revivals run by Robert Robertson

Now in the custody of Pixie Robertson.

1. J. Nicolson, Traditional Life in Shetland

2. Interview with R.N. Robertson, March 2000

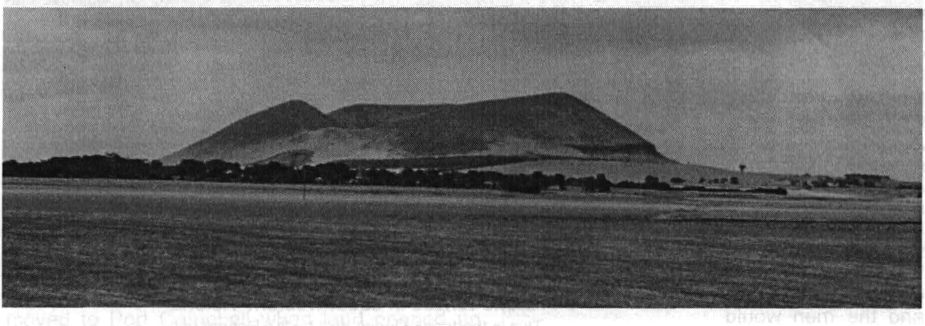

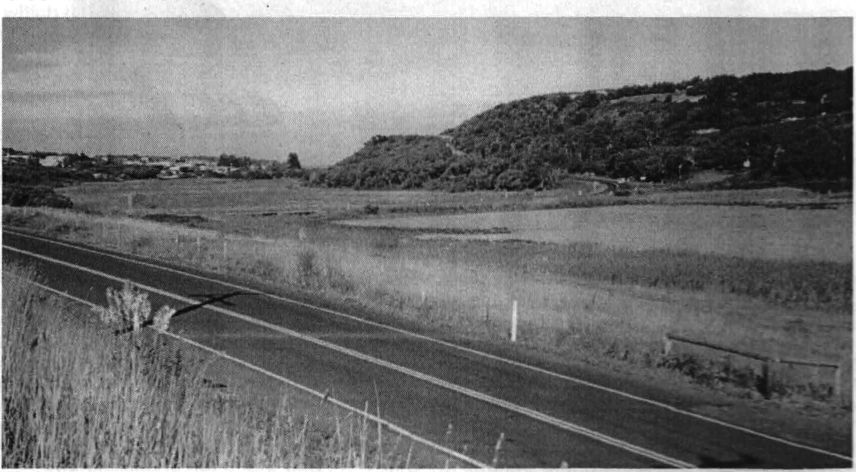

Mt Elephant: A recent view

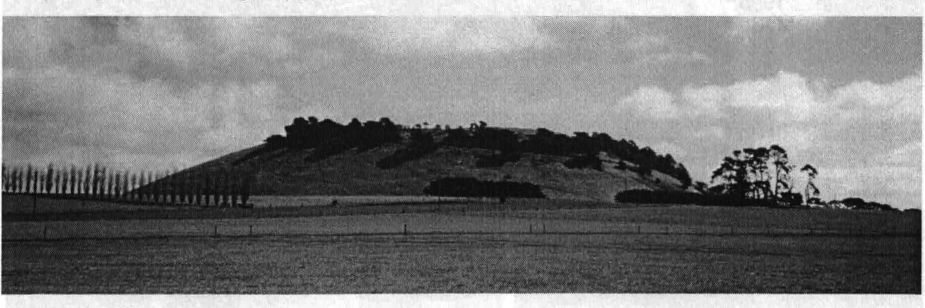

As family members joined Arthur in the western district of Victoria the family settled at Lake Tooliorook near Derrinallum. 1 It was here that the eldest son, James, married in 1868. The family was still there in 1870, when Agnes and Margaret were married. Whether Arthur took up land in the area I do not know, but it seems probable. One story, which l have not been able to substantiate, suggests the Robertsons selected land in their name, on behalf of people called Manifold, as a ploy to get around the regulations limiting how much land one person could select. Lands department records show there were five lots in the name of J Robertson in the township of Derrinallum in 1867. Mt Violet, Mt Elephant and Mt Leura have all been suggested as a possible site for their first home. Certainly Robert had a sentimental attachment to the area where he spent his teenage years, writing a song about Mt Leura’s fields of green, “There an old slab cottage stood / In a gently sloping wood” 2

'Mt Leura's fields of green'

By the year 2000 the “gently sloping wood" has almost diappeared and European poplars have been planted.

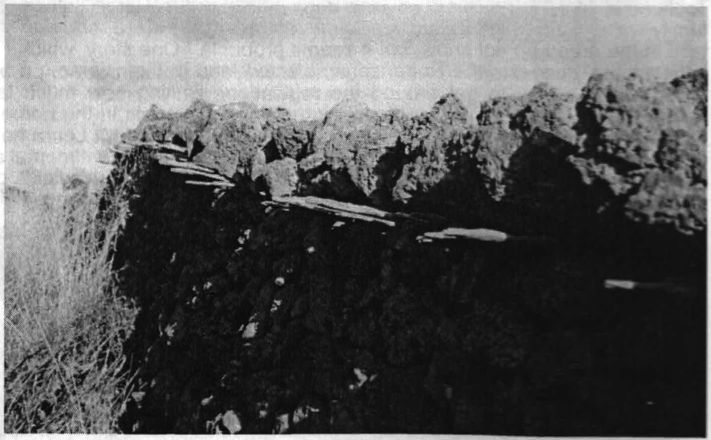

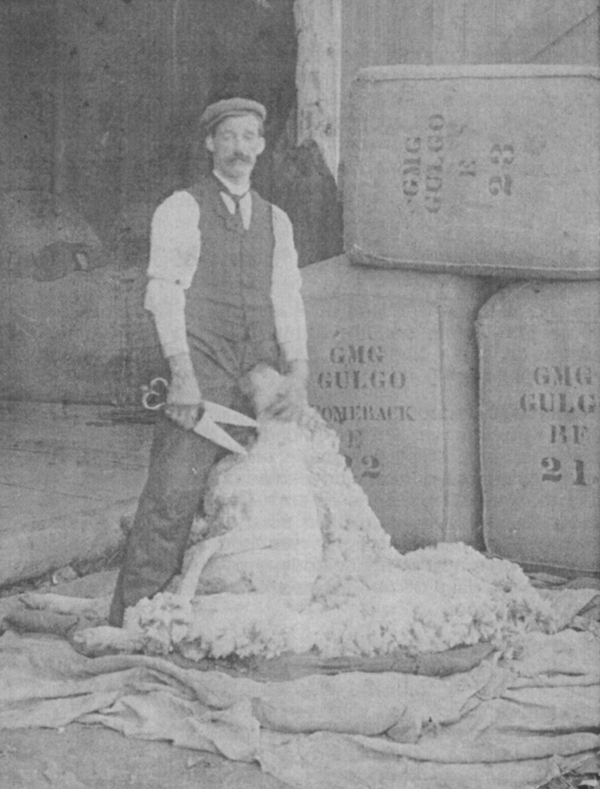

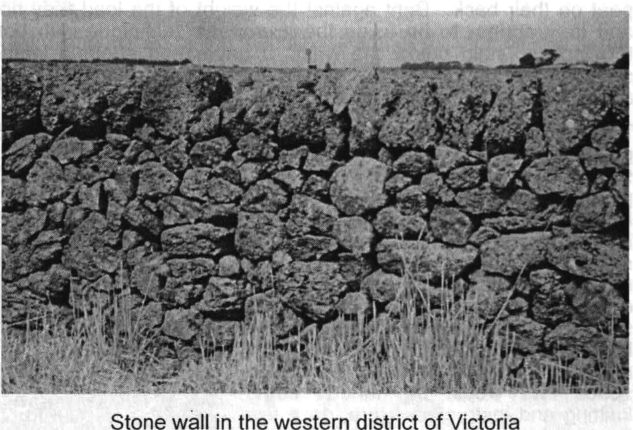

Arthur must have quickly realized the potential for earning a living by building dry stone walls and sheds, a skill he and his sons brought from Shetland. The walls had the multiple advantage of providing fences for impounding stock, marking boundaries, providing fire breaks, and clearing the land of some of the millions of stones which dot the area as a result of volcanic activity in the long ago past. The Robertsons gathered around them a team of fence builders which undertook contract work for local landholders in the area around Camperdown, Derrinallum, and Skipton, east to Pomborneit in the Stoney Rises and as far west as Ellerslie and the Ballangeich and Drysdale homesteads. The stone fences at Larra Station were built by the Robertsons in 1869-70. This includes the stone gateway that was originally the entrance to the homestead, and which is now part of the public road. There is supposed to be a ‘signature’ mark on one of the stones but l was unable to find it when I visited the area in 2000. Those working with the Robertsons included Michael McCue, who would marry Agnes, and a man named Murnane, about whom l know nothing other than his name. 3 Progress was at the rate of ‘one and a half chains per day' and the men would camp out as they progressed along the extending fence line.

Stone fences in western Victoria.

This is the type of fence built by the Robertsons. >

Many of the stone fences in western Victoria are now protected under conservation legislation and the Corangamite Arts Council produced a book about the fences in 1995. 4 John McCue gives an account of Robertson involvement building the fences on page 83 of the book. An error in this account describes Arthur as John’s great uncle, when he was in fact referring to his great grandfather.

Stone fence with embedded wooden slats to deter rabbits >

Stone fence with embedded wooden slats to deter rabbits >

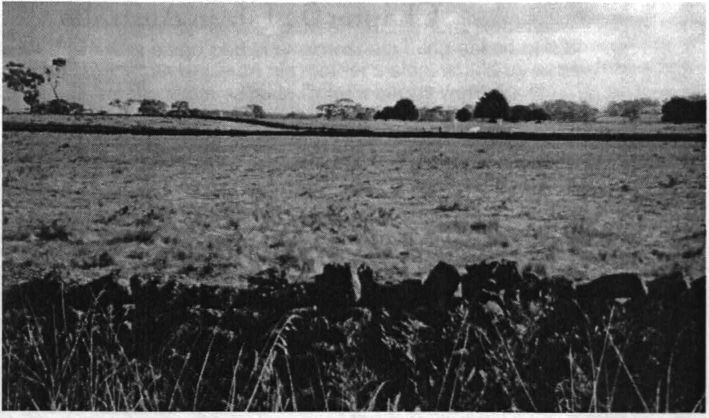

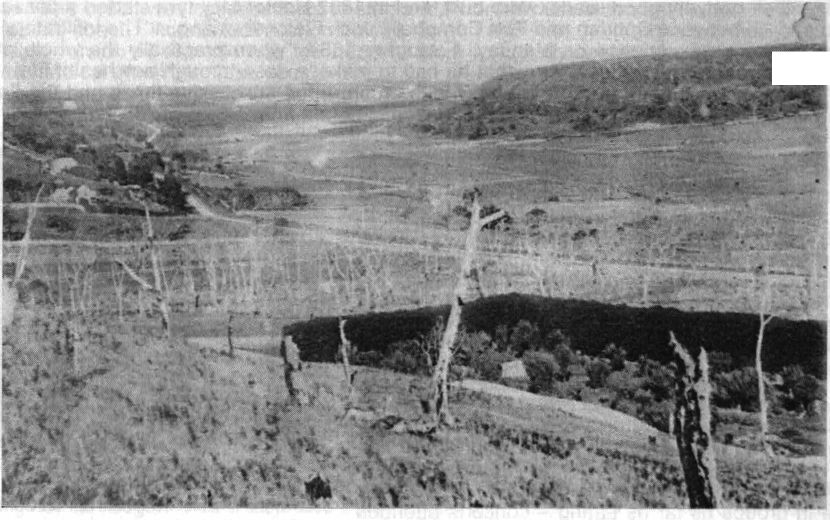

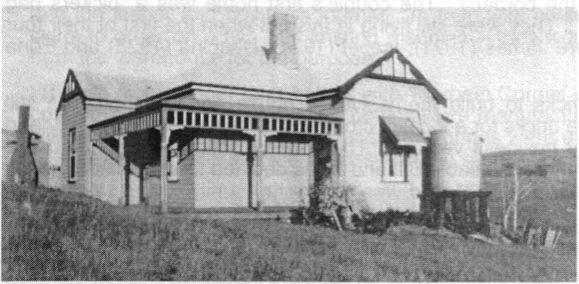

From Derrinallum the family moved to Port Campbell. The chronology of the move is not clear, but it probably took place over a period of time, with family members moving about south western Victoria as the menfolk took labouring jobs or did contract work fencing and shearing. Lonely for the sea, Arthur Robertson visited and selected land at Port Campbell as early as 1865, but did not take possession of it until 1871. Robert writes, “When father first visited Port Campbell it was a veritable ‘no man‘s land.’ The Government refused him the selection of land where the town now stands, reserving it for a town. Land further up the river was obtained, and there he built a five-roomed stone cottage." 5 This land, near to the cemetery, is on the northeastern side of the bridge over Campbell Creek. On the Lands Department map it is marked as Lots 10 and 10a, divided by the present road to Timboon. (See the map on page 32.)

It seems the family’s early efforts at farming in the Mt Violet area were not a success. Arthur is quoted as saying, ‘Come boys, if we can’t make a living from the soil, we’ll make it from the sea as we have always done.’ This is supported by a comment added to a report about James Robertson‘s land reproduced in Appendix 4, which refers to another file, [possibly one about Arthur's land?]. It states, “The applicant and his sons were fishermen or connected with fishermen in Scotland and their ambition is to found a fishing station at Port Campbell." The idea came to nothing, for the Port Campbell coastline, with its the steep dangerous cliffs and off-shore winds, was not suitable for a fishing industry.

Heytesbury Forest >

A remnant section photographed in 2000. The area around Port Campbell was originally covered by dense forest which had to be cleared before crops could be planted.

Not everyone was happy with the move to Port Campbell and Lottie Dickins reported, “The family moved to Port Campbell when land opened up there because of their love of the sea - giving up better land and a better farm for poor land and virgin forest. Grandmother R was very upset as she did not wish to leave the district where they were established. All the women rode down side saddle through the Heytesbury forest - now cleared away and all farming land.“

Several sources suggest that the choice of Port Campbell was associated with the cliffs, which reminded the family of the cliffs at Eshaness in Shetland. The Eshaness cliffs are black, in contrast to Port Campbell's yellow sandstone.

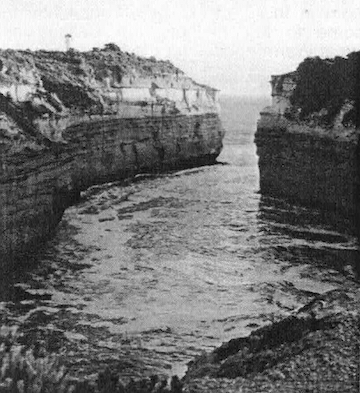

Eshaness on the west coast of Northmaven Shetland. — Loch Ard Gorge

near Port Campbell, Australia.

Margaret Henderson’s concern was probably well justified as descriptions of the early days at Port Campbell indicate a hard life. The isolation of the settlement and the difficulty of clearing dense forest and establishing crops such as potatoes and oats, meant food was sometimes scarce and families often went hungry. Obtaining supplies such as flour and tea involved a ride to Cobden - one day there, stopping overnight, and another back again. Robert writes, "... you must know there was no fatted calf which had ever been seen at Port Campbell in those early times. There was no grass to fatten a calf on.” However Arthur believed the area would prosper. "He tested his faith by making a small grass-tree area wallaby proof, digging it up, sowing oats and fertilizing it. He reaped a satisfactory return, which assured him that what he had done in a small way could, and would, be done in a large way some day” 7 Years later the use of super phosphate and trace elements would make the area more suitable for farming.

Neighbours of the Robertsons were Mr and Mrs Hector Mclntryre and Mr and Mrs John Henderson (not related to Margaret). The families became friends, giving each other support through difficult times, particularly the women who were often left on their own when the men were away working. The Mclntyre’s daughter was the first white child born in the area and Margaret attended her birth. The first death at the Port was the Henderson’s child, “which cast a shadow over every heart in the settlement.” 8

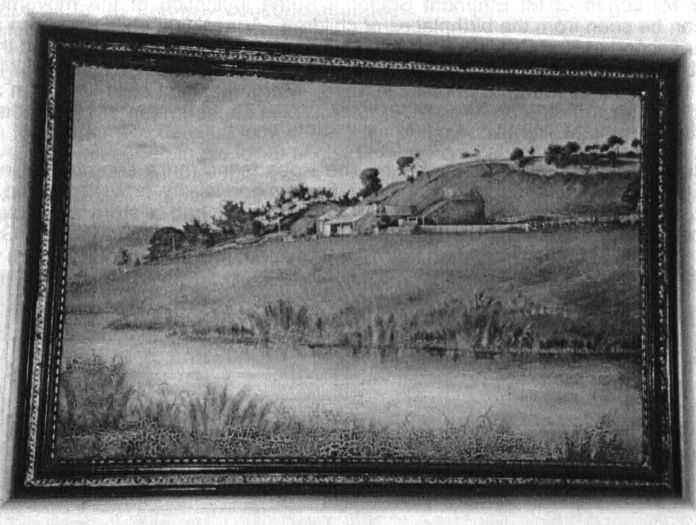

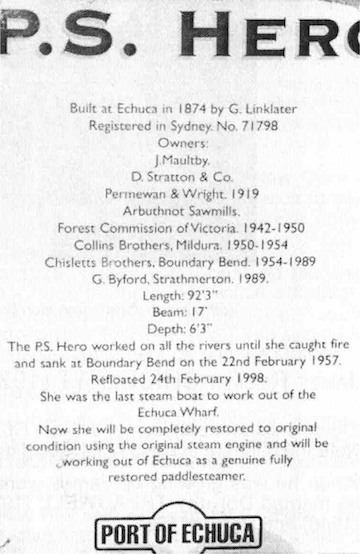

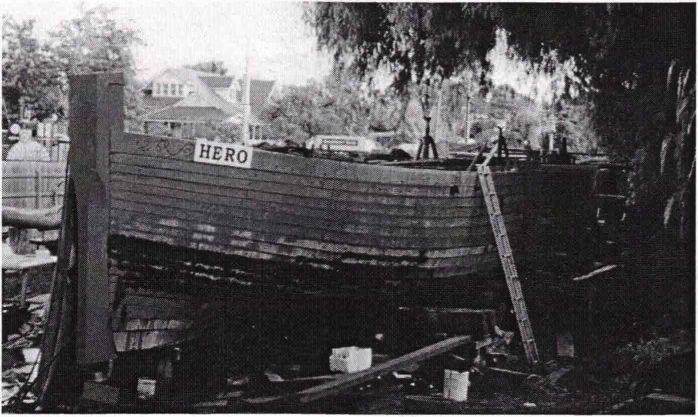

Arthur quarried stone out of the cliff near the lower section of the present cemetery, rolled it down the hill, cut it into suitably sized blocks, burned the lime, slacked it and mixed it, and built a substantial five roomed house for his family. lt became known locally as ‘the old stone house’. There is an old photo showing section of the house and a painting by Miss Maud Brown hanging above Di and Jeff McCue’s dinner table at Port Campbell. A more recent representation of the house was painted by Valerie Ward shortly before her death in 1990 and hangs in Gus Ward’s house.

The Old stone House. >

The Old stone House. >

An early photograph of Port Campbell showing the bridge over Campbell Creek and a section of the Robertson's house. This photograph was used by Francis Robertson Saunders on the cover of her tract ‘My Grandmother's Prayer’.

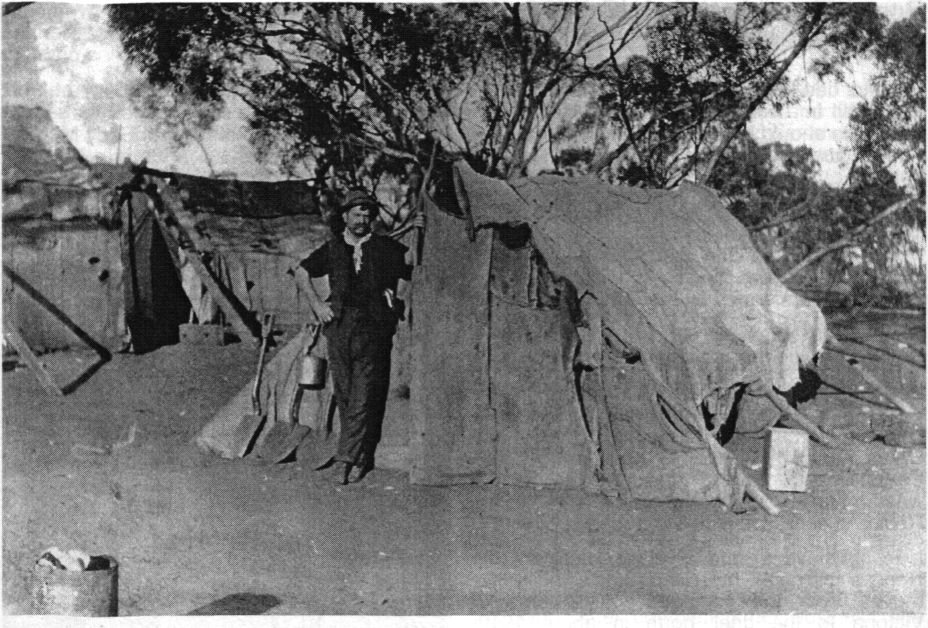

While the house was being built, Arthur and Margaret lived in a 6 x 3 feet (roughly 2 x 2.5 metres) tent in the cavity from which the stone had been excavated. Agnes’ daughter, Robina McCue, was born in this tent in 1872, Agnes having come to her mother from Ballangeich (near Warrnambool) for the birth.

The stone house was completed in July 1872. The local stone was not the most ideal building material and a verandah surrounding the house was essential to protect it from the weather. Despite this protection the stone absorbed moisture and for much of the year the walls were green with damp. The stone house was eventually demolished. Margaret Haine remembers seeing piles of stones were the house had stood, when she was in Port Campbell in 1926. All the Robertson brothers selected land along the Campbell Creek valley, as did Michael McCue and George Chislett, who married into the family. The report mentioned previously, written by a mounted constable after his inspection of James’ block in July 1874, tells us the area was ‘heavily timbered and covered with dense scrub’. Robert describes an evangelising visit to the Mclntyre’s house at about this same date, “He at that time was a shepard [sic at Glenample where the wild dogs were troublesome to the sheep. Mrs Mclntyre appraised her husband of the proposed visit. Arriving at the hut we found him standing with his back to a log fire, shirted and trousered, with a saddle strap round his waist, his feet in unlaced boots.” 9

The lives of the second generation in Australia fall into two phases divided by the religious revival of 1874. The division is not sharp and I am sure the change from hard living settlers, struggling for survival, to respected God-fearing preachers, occurred more gradually and over a longer

page 27

period than Robert Robertson, writing in ‘The Port Campbell Revival’, seems to indicate. I write about the Robertsons and Christianity in Chapter 13.

Robert not only relates the Robertson family’s spiritual conversion, but he also gives us glimpses of the environment in which the family lived:

... homes scattered through the forest in winter time the bridle tracks were just streaks of gutters. There were no roads, no bridges and no culverts. Swamps, rivers and creeks were all full of water. To cross at the mouth of a river on a moonless night when a storm was on was to me rather gruesome. The river one was crossing always seemed to be much lower than the thundering breakers roaring outside. It seemed as if the horse and yourself must be overwhelmed. The waters were swirling around the horse’s legs as he waded through, and the sands under his hoofs were in constant motion. At such times I always had a feeling my horse was sensitive of danger. He and I were always glad when we were safely over. 10

Stories suggest a wild undisciplined bunch in the early days. There is certainly enough anecdotal evidence to suggest the Robertsons were heavy drinkers, with whisky their preferred drop. Lottie stated, “All the Robertsons were heavy whisky drinkers except Robert who was unable to drink because it made him ill. Uncle Willie and Jim and the sisters gave up drinking after becoming religious?" 11 Unlike his brothers Arthur Jnr continued drinking alcohol and Lottie told of living with her Uncle Arthur and Grandmother cum Aunt, Margaret Rutherford Cairns Robertson at Port Campbell, to help look after Margaret in her old age. Arthur would come home drunk and Lottie was terrified he would set the house on fire as he staggered around with a candle.

The Old Stone House

Painted by Miss Maud Brown in the 1880s. Note the scorch marks around the frame, which suggests the painting has been through one of the house fires mentioned in Chapter 7.

The Rev Jack McCue, when telling his daughters Marjorie and Marion about his childhood, related that the Robertsons were often so drunk they could hardly stand up. As a child, Jack would be put to sleep with a nip of whisky. It was Jack’s early experiences with the effects of the demon drink that turned him into an ardent temperance worker in later life. It certainly appears as if Michael McCue continued drinking heavily all his life and this might have been a point of contention between him and Agnes.

There are two stories about Robert in his late teens or early twenties. The first incident resulted from a disagreement with the local innkeeper. Robert rode his horse into the bar and with his whip he knocked all the bottles off the shelves. The second story involves the local coach

page 28

service. The coach was not scheduled to stop and Robert’s companion bet Robert £10 he could not stop the coach. Robert took him on, raised his gun and shot the lead horse. A slightly more charitable version of this tale has the need to stop the coach because a woman giving birth needed medical attention. Take your choice, either way the horse ended up dead.

In writing about his parents’ Christian faith and the family prayer sessions, Robert himself seems to make a small admission about his parent’s concern for their children's lifestyle by stating, “ln spite of prodigality, [their] prayers were priceless and painful to kick against. From the conversion of my parents until the salvation of their family would be over thirty years, giving a long time of prayer for these two.” 12

Lottie Dickins gives us a Cairns’ view on the Robertson family. Her mother and Uncle Sam, both Cairns, told her “the Robertson clan was very strong, which was never overcome and they shared the good and the bad. On one occasion they turned up at the Cairns property at Skipton and killed a milking cow for a feast. lf one of them experienced good fortune the others expected to share it and when one lot was having a hard time they would call on another family member to support them.” 13 This closing of ranks sometimes made it difficult for outsiders to be accepted. Arthur Snr made no secret of his hatred of the Sassenach - a term covering the English and Lowland Scots - and he proudly proclaimed his Norse descent. It seems Mick McCue, an Irish Catholic, had trouble being accepted by the family. Jack McCue claimed his grandfather never spoke to him when he was a child.

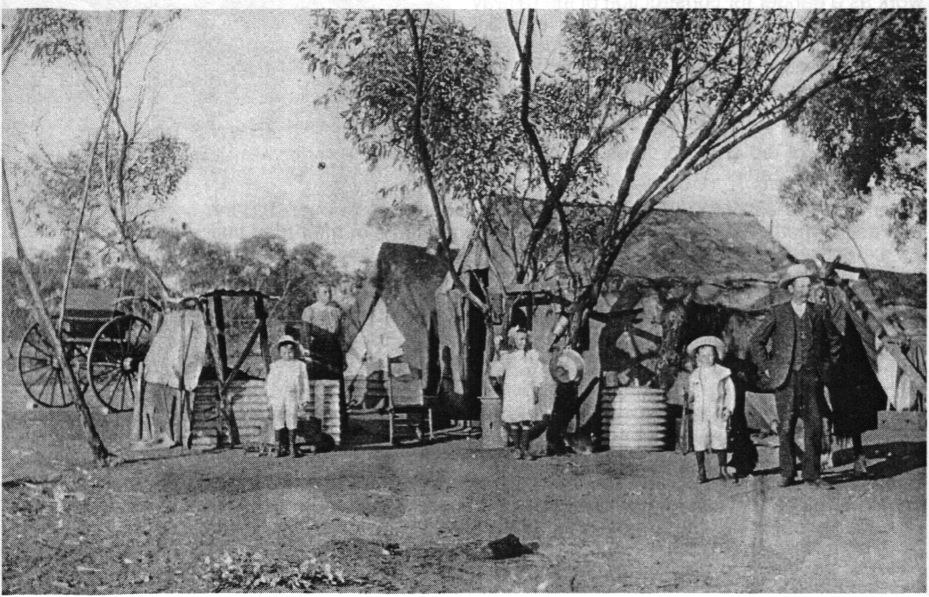

While the land was being cleared and crops established, other sources of income must have been needed and at the time James’ land was inspected in 1874, he was away from home, working for Mr Logan of Mt Elephant Station. Some indication of the movement of family members can be seen from the birthplaces of children. Agnes’ first child was born at Tooliorook in 1871, her second at Port Campbell in 1872, her third at Tooliorook in 1873, and the last two at Port Campbell. James’ first two children were born at Darlington in 1869 and 1871, the third at Cobden in 1873 and his fourth at Ellerslie in 1876. Margaret’s first child was born at Tooliorook in 1872 and her second at Ellerslie in 1876, her fourth in Melbourne in 1879 and the rest at Port Campbell.

Gradually the settlement began to prosper. The Robertsons ran a shop in the lean-to on the southern side of the house, supplying drapery, leather goods, dry provisions, and home made cider. Lottie related that in the early days, “Grandfather R had a store and sold cider. The excise officer Harrison analysed the cider and found it an intoxicating drink and Grandfather R was fined? 14 A similar story is attached to William Adie, but this time involving plum wine. These could be different versions of the same incident.

Present day view of Port Campbell and the site of the Old Stone House

page 29

Roads, albeit not very good roads, were built, and in 1882 Hector Mclntyre started a passenger coach service between Cobden and Port Campbell. Jack Fletcher writing in ‘The lnfiltrators’ tells of Mr McIntryre’s experience on Monday, 4 January 1887, “when practically the whole of the forest was on fire. The records show that he had to make "a dash through patches of fire which walled up each side of the road; the buggy was on fire three successive times and the flames extinguished, and the seat was burnt from beneath him before he reached his destination". 15

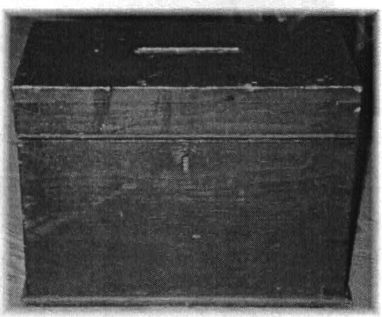

In 1888, the newly built community hall was used as a polling place for elections. The original ballot box is in the Port Campbell museum with a notice attached to it saying Arthur Robertson acted as polling clerk. ln the 1890s a shed attached to the old stone house was used by Bill Port as a cobbler’s shop. This was probably the same lean-to used earlier as a shop. Bill was an uncle of Jessie Port, wife of Arthur Ward in Generation ‘D’. He died in the middle of the decade at the age of nineteen or twenty from a ruptured appendix.

Ballot box >

Used in the first elections held at Port Campbell

John McCue writes that Arthur “went to Warrnambool regularly crossing the Curdies River at Peterborough. If the travelling was by horseback, the shorter trip was taken by Boggy creek - the horses ‘swum’ over and a break often made at the Le Couteurs. Trips were made in groups as far as Laang - concerts attended and contributed to. Horses were traded - cattle exchanged or sold - families intermarried - a new strata of living was established.“ 16

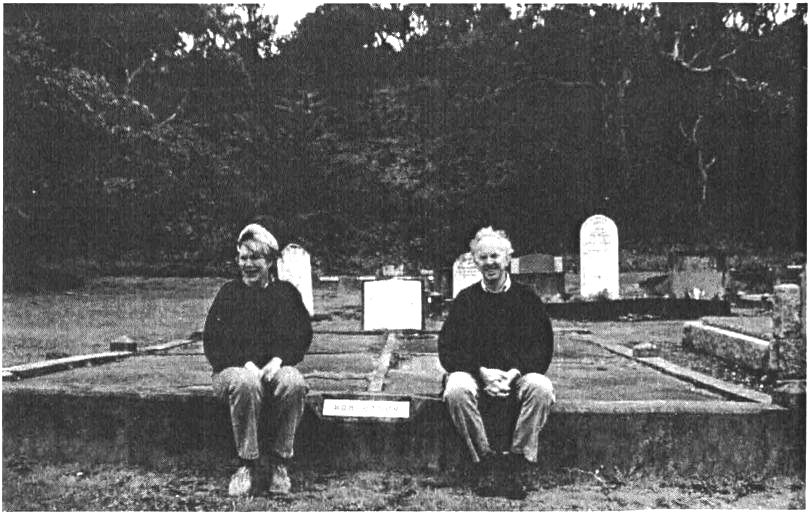

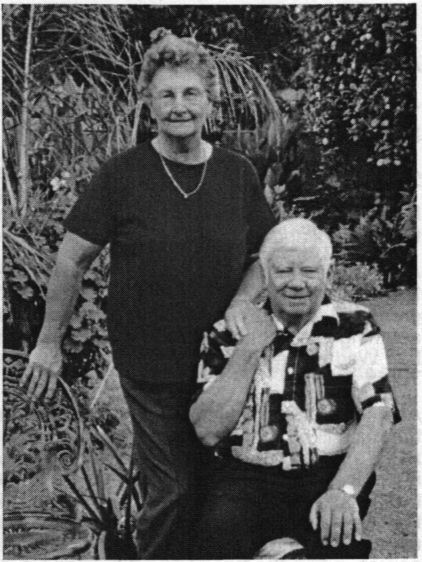

With the coming of the new century, we leave Margaret Henderson and Arthur Robertson behind and move on to take a more detailed look at the lives of their children. Margaret died at the age of seventy-five and was buried in the lower section of the Port Campbell cemetery on 26 October 1887. Arthur would live for another nine years. He died at the age of eighty-one and was buried beside his wife in the family grave on 30 December 1896. Other members of the family would later join them there.

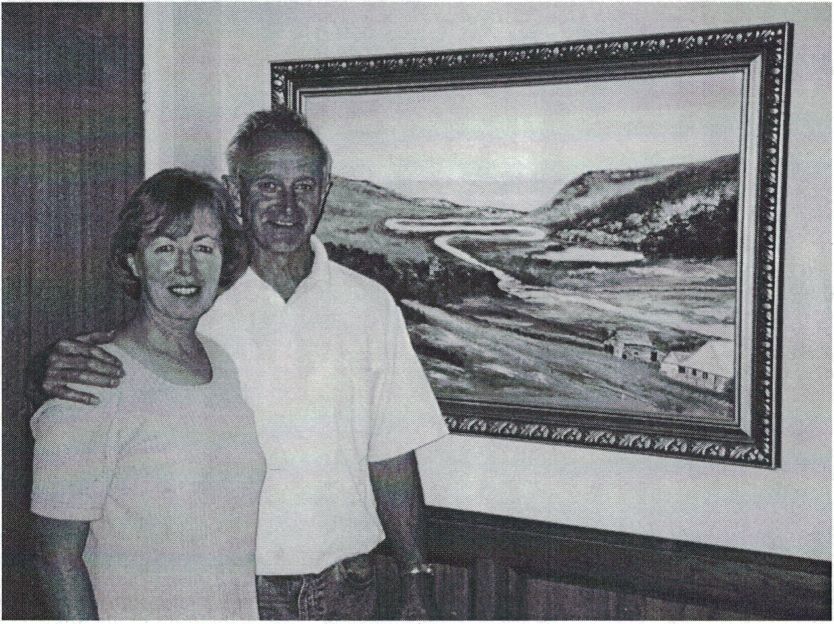

Robertson Family Grave, Port Campbell Cemetery

Seated on the grave are Graeme and Heide Robertson.

page 30

An early view of Port Campbell from the hill

1. The name of the settlement called Tooliorook was later changed to Derrinallum.

2. See Appendix 5 for the full text of ‘Mt Leura's fields of green’.

3. The Murnane name appears quite frequently in histories of the Heytesbury Shire.

4. J. Black, ‘lf These Walls Could Talk - A report of the Corangamite dry stone walls conservation project’

5. R. Robertson, ‘The Port Campbell Revival', p.49

6. Lottie Dickins recorded by her daughters Marie Nemec and Margaret Worrall

7 R. Robertson, ‘The Port Campbell Revival’, p.13 and p.49 respectively

8 lbid, p.8

9 lbid, p.17

10. R. Robertson, ‘The Port Campbell Revival’ pp.7-8

11. Lottie Dickins recorded by her daughters Marie Nemec and Margaret Worrall

12. R. Robertson, ‘The Port Campbell Revival’, p.7

13, Lottie Dickins recorded by her daughters Marie Nemec and Margaret Worrall

14. lbid. According to Lottie, Harrison was the great grandfather of a General Harrison and Harrison family lives often touched Robertson family lives.

15. J. Fletcher, ‘The Infiltrators - a History of the Heytesbury 1840-1920’, p.97

16. Notes made by John McCue

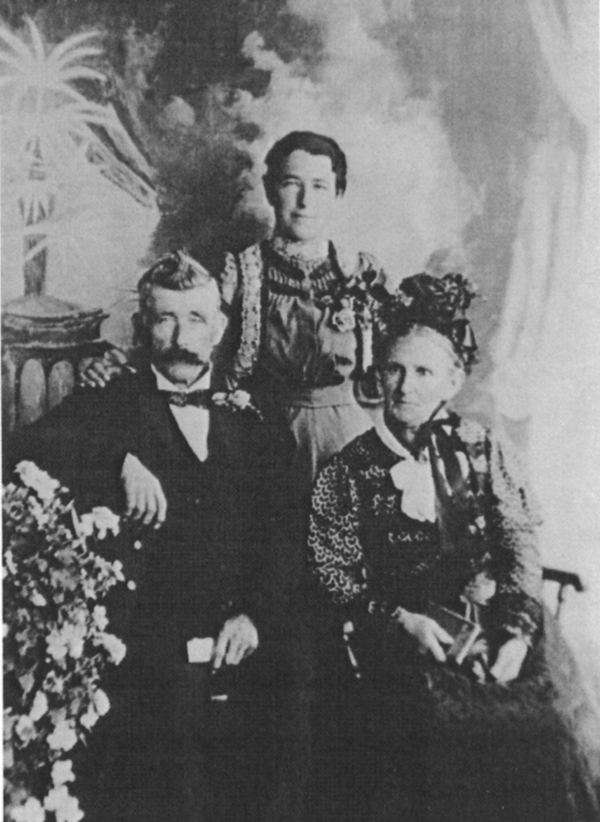

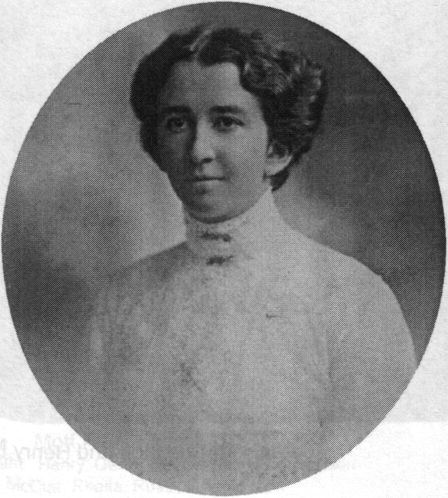

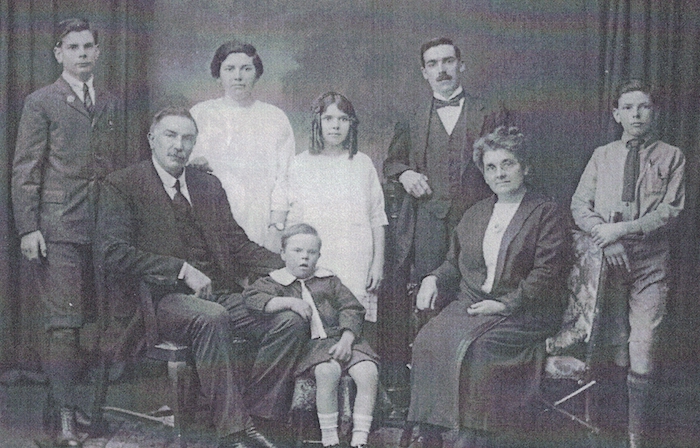

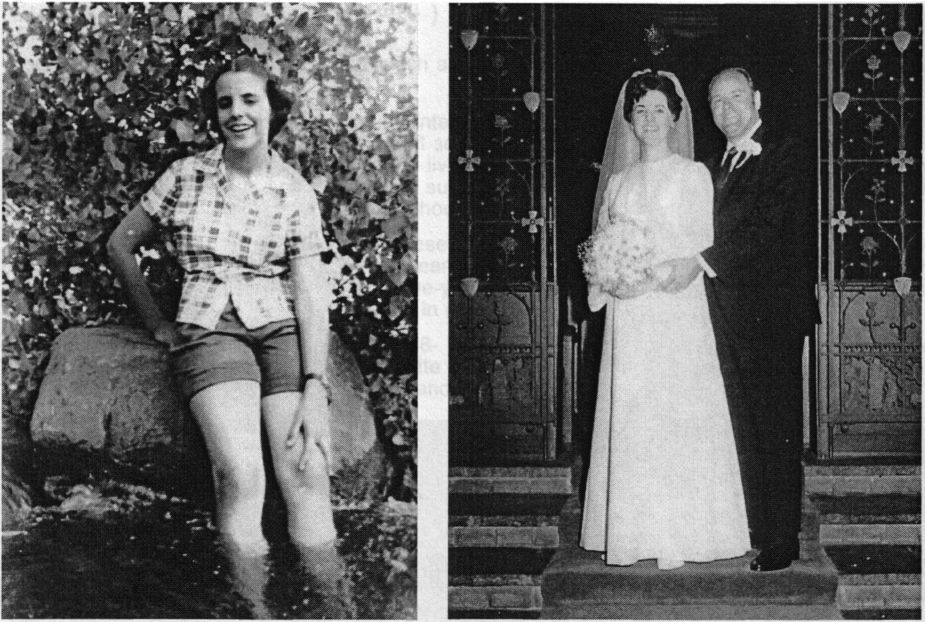

Born 1838 - Died 1918 - Married name McCUE

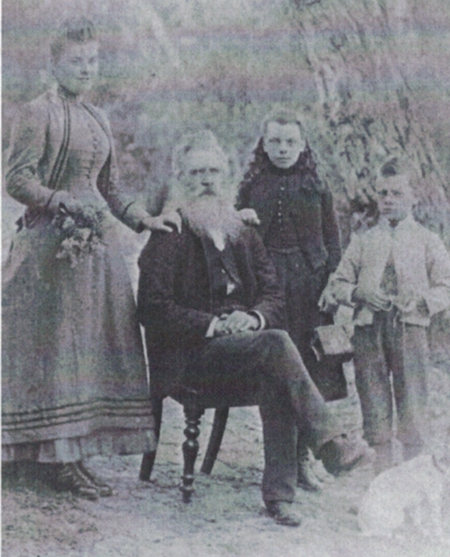

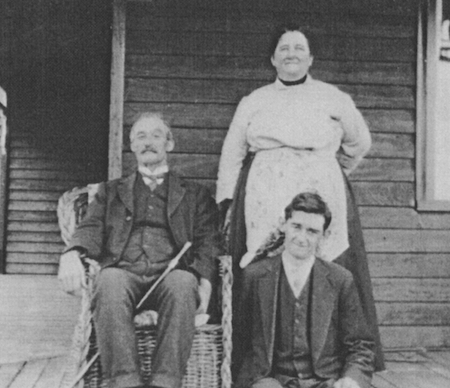

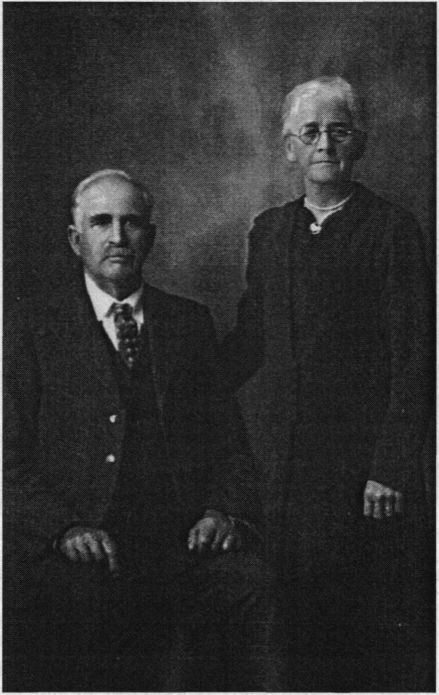

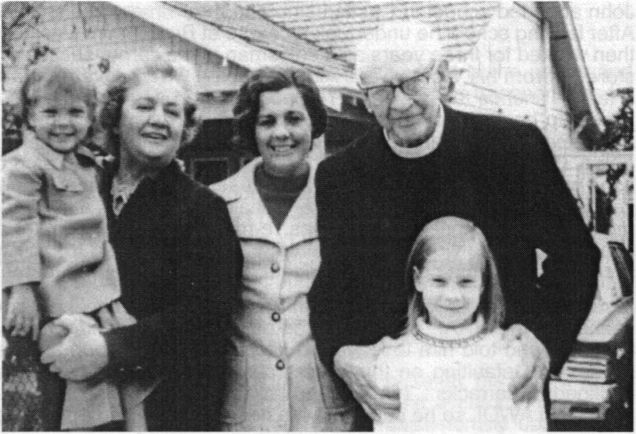

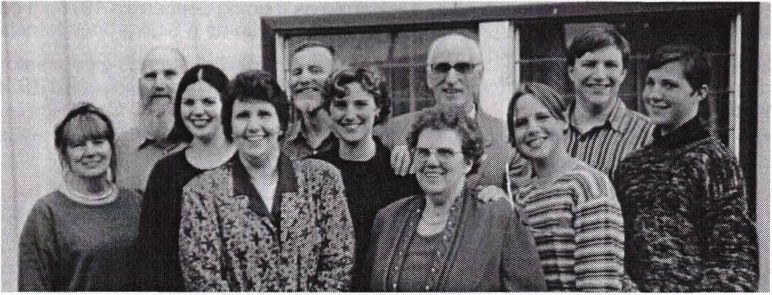

Agnes Robertson with her father Arthur Robertson

Agnes was the eldest of Margaret and Arthur's children and she was born at Scalloway, Shetland on 30 March 1838. Being the first-born girl she was named after her maternal grandmother Agnes Williamson. I have no stories about Agnes before she came to Australia.

Accompanied by her sister Margaret and brother Arthur, Agnes arrived in Australia in September 1867, after a journey of just under three months aboard the ‘John Temperly’. Agnes was twenty-nine years old and described on the shipping list as a knitter. John McCue tells us that Agnes provided a calming influence on the younger women she was travelling with when their ship was overtaken by a storm and the hatches battened down for several days. 1 After their arrival Agnes, Margaret and Arthur joined their parents at Derrinallum in the Victorian western district.

On 12 January 1870 Agnes married Michael Grace McCUE (1831?-1916) at Lake Tooliorook. The service was conducted by the Rev Edmund S Bickford, a Wesleyan Minister. Witnesses to the marriage were James and Arthur Robertson. Agnes and Michael had two sons and three daughters, Barbara (1871), Bean (1872), Arthur (1873), Aggie (1877) and Jack (1882). The family must have lived at Tooliorook for a time, as two of the three older children were born there. Later they took up land at Port Campbell where the two youngest children were born. It seems the marriage was not happy and Agnes is noticeably absent from family photos, which show Michael with some of his children. When their youngest

page 32

child was seven (about 1889), Agnes and Mick separated. Agnes and her eldest son, Arthur, lived at Smokey Point, while Mick lived with and cared for the other children in town, in a house on the corner of McCue and Lord Streets, Port Campbell.

The allotments shown are taken from an early Lands Department map and are referred to in the text.

page 33

Smokey Point, which is still a feature in the Port Campbell district, acquired its name from the Robertsons, according to Gus Ward. 2 Travelling by horseback to reach Port Campbell through the thick Heytesbury forest and coming out on the hill at Smokey Point gave the traveller a first sight of the ocean. It was customary to stop here for a rest and have a smoke before travelling down to the settlement.

We have lots of information and a lot of stories about Michael Grace McCue. The following account of his life has been put together from information supplied by his grand daughters, Marjorie Mathieson and Marion Parker, and other family members, as well as details gleaned from documents and rough notes left by John Collins McCue and supplied to me by John’s children, Jeff McCue and Helen Krigsman.

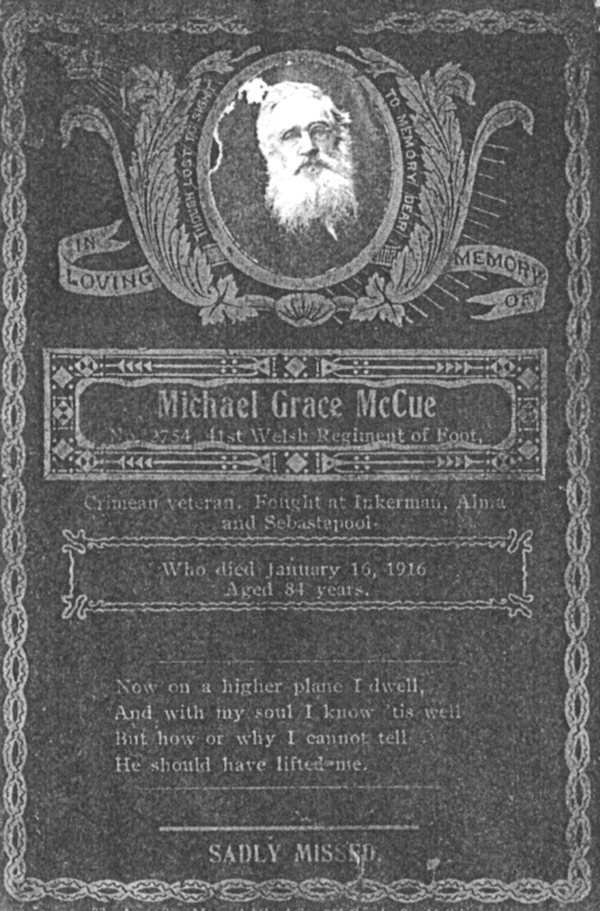

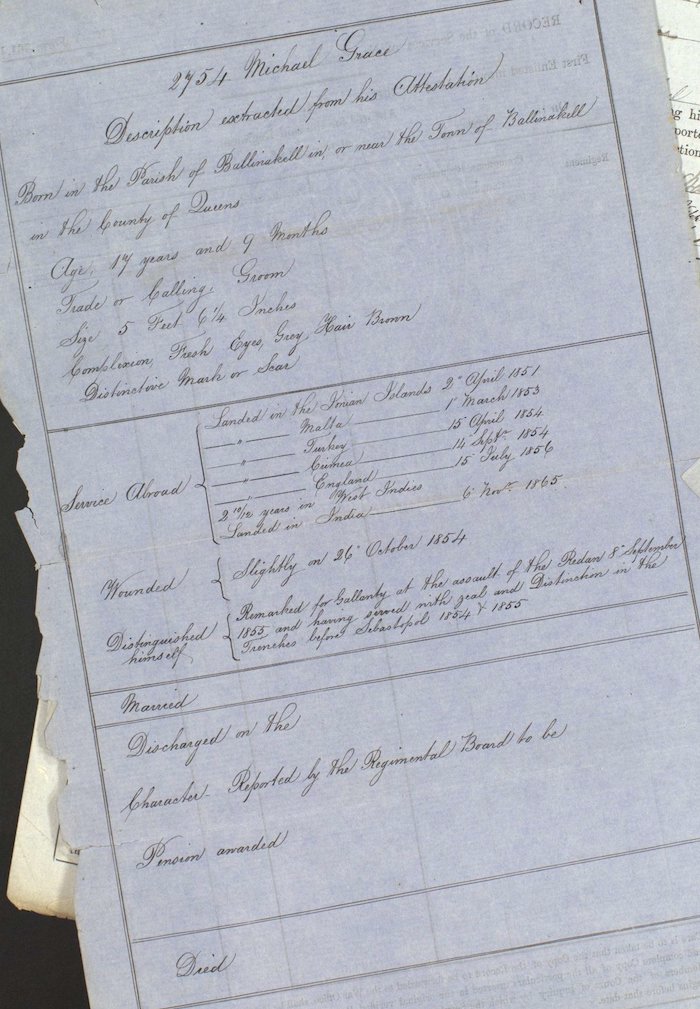

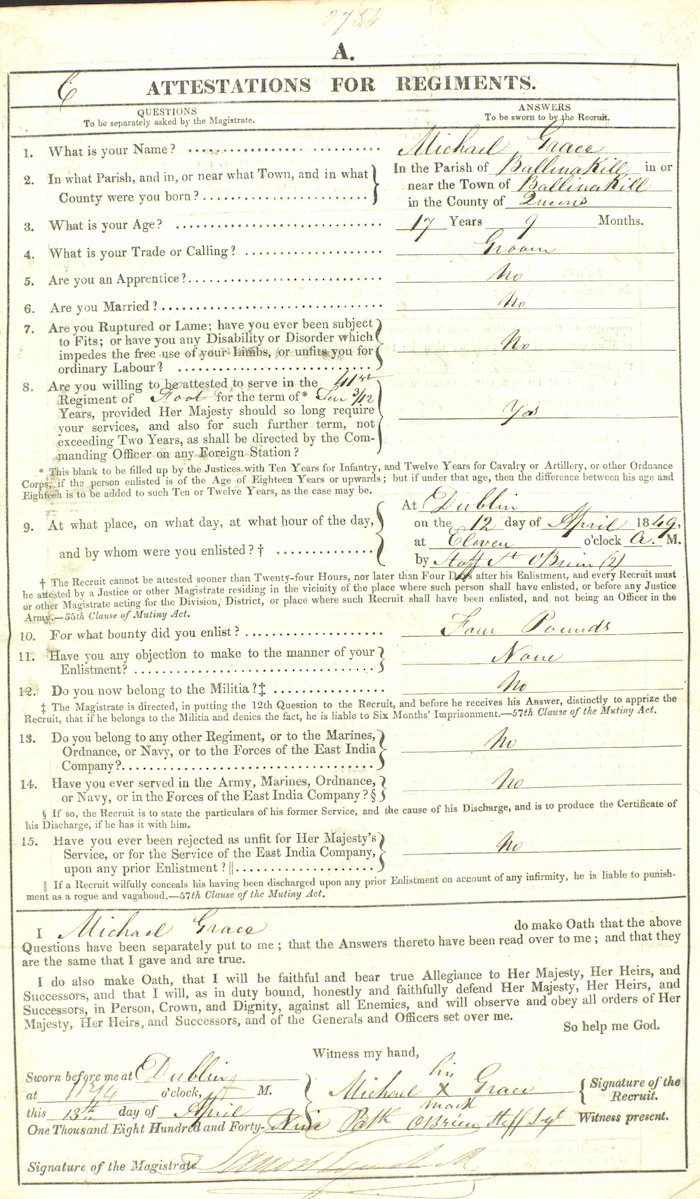

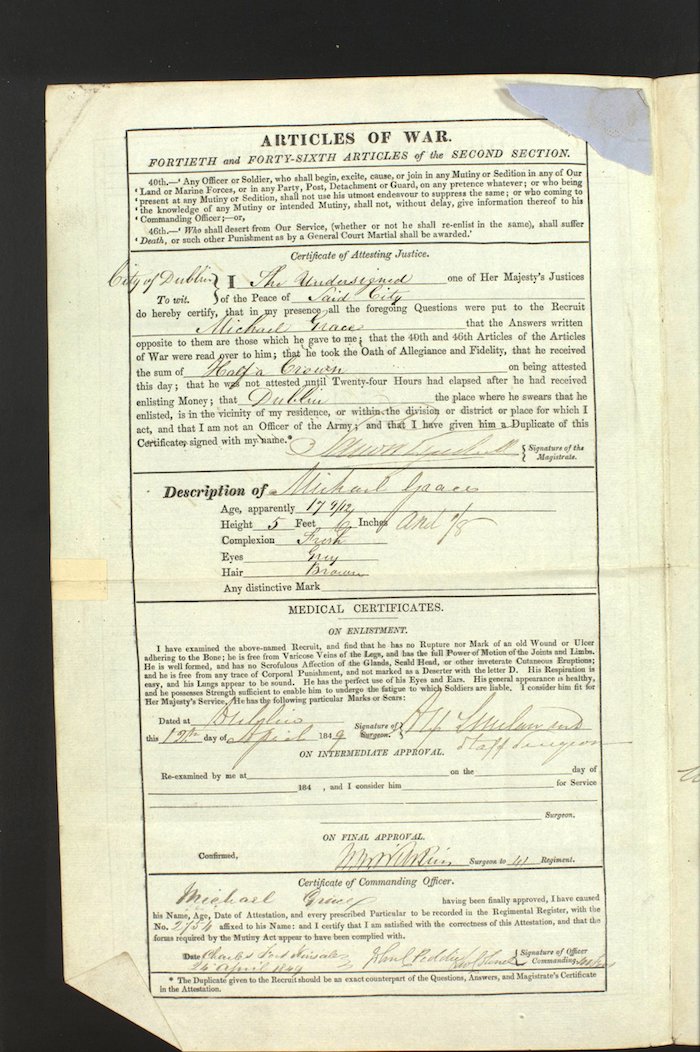

Mick was born at Ballinakill, Leix (pronounced Leash), Ireland, the illegitimate child of Margaret Grace. The date of his birth is uncertain but was possibly 29 September 1831. 3 On Mick's marriage certificate his mother’s name is recorded as Margaret Grace and his father's as John McCue, farmer. On his death certificate his mother is recorded as Margaret McCue nee McDonald and his father as John McCue, with place of birth as Queenstown, Clare. This is confusing. [Death certificates are notoriously inaccurate because the subject is not available to supply the appropriate information about themself!]

Mick was born at Ballinakill, Leix (pronounced Leash), Ireland, the illegitimate child of Margaret Grace. The date of his birth is uncertain but was possibly 29 September 1831. 3 On Mick's marriage certificate his mother’s name is recorded as Margaret Grace and his father's as John McCue, farmer. On his death certificate his mother is recorded as Margaret McCue nee McDonald and his father as John McCue, with place of birth as Queenstown, Clare. This is confusing. [Death certificates are notoriously inaccurate because the subject is not available to supply the appropriate information about themself!]

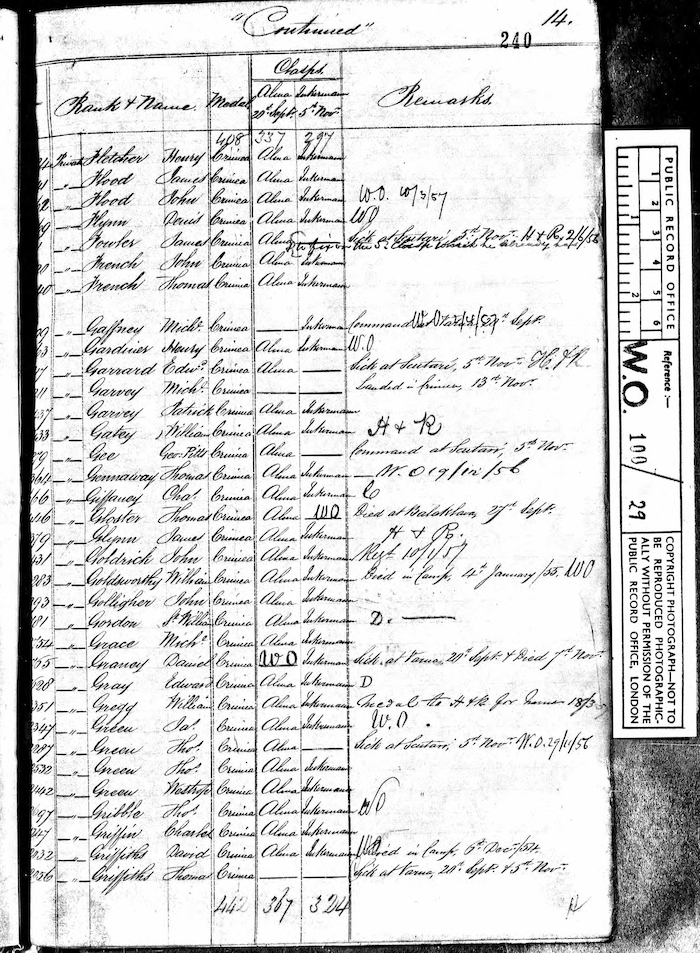

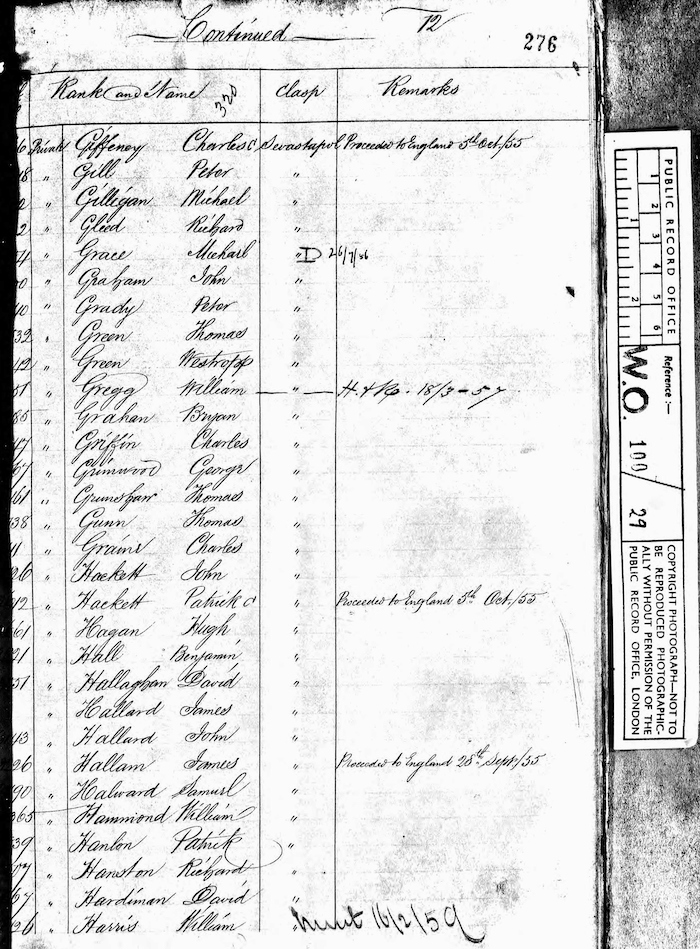

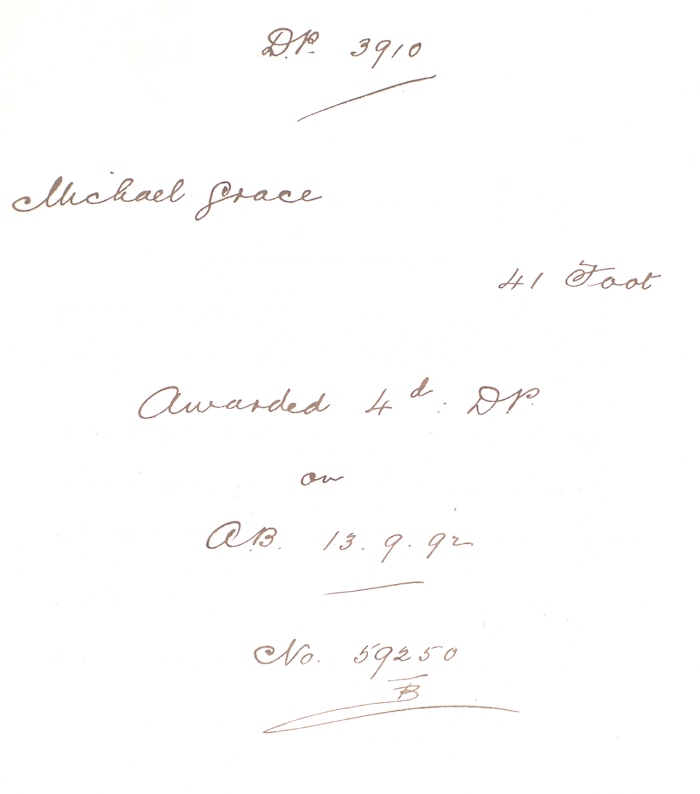

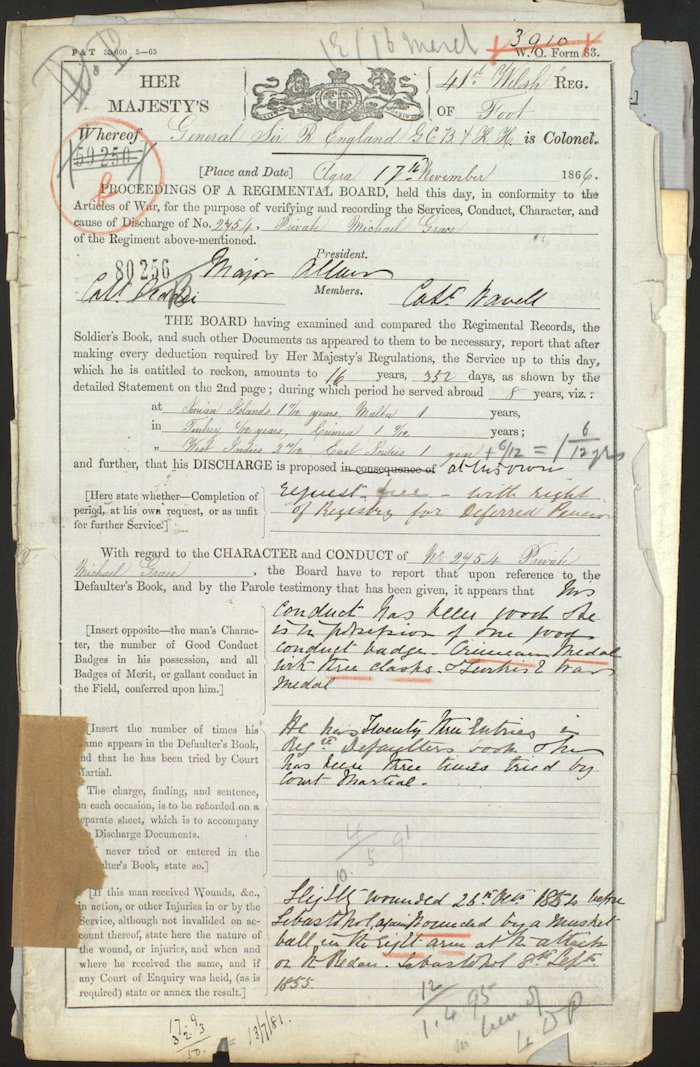

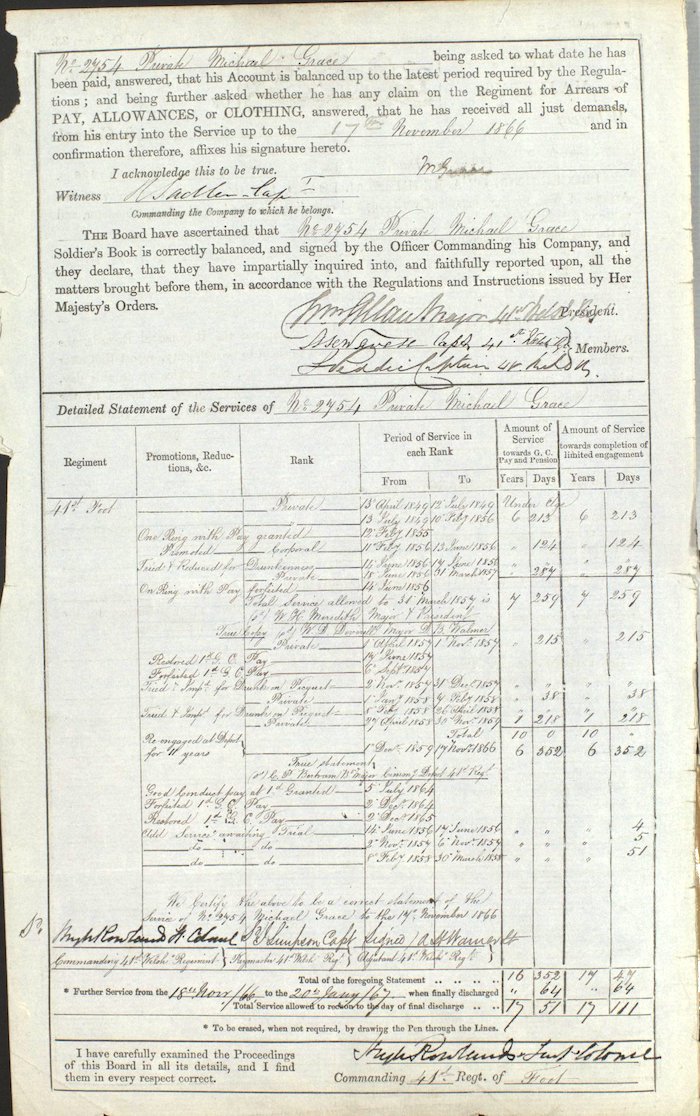

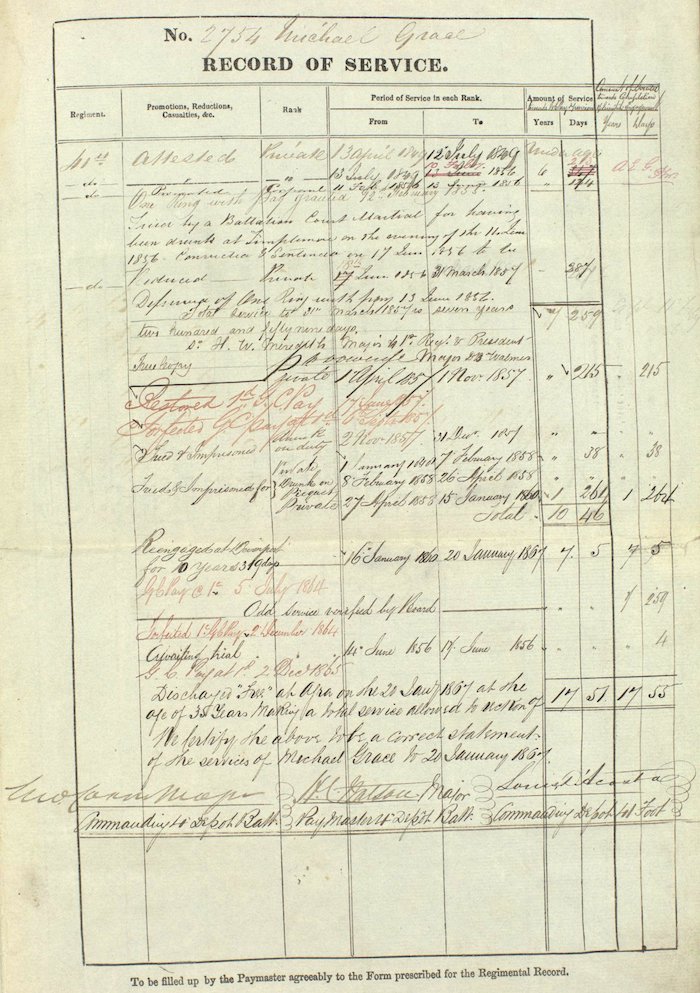

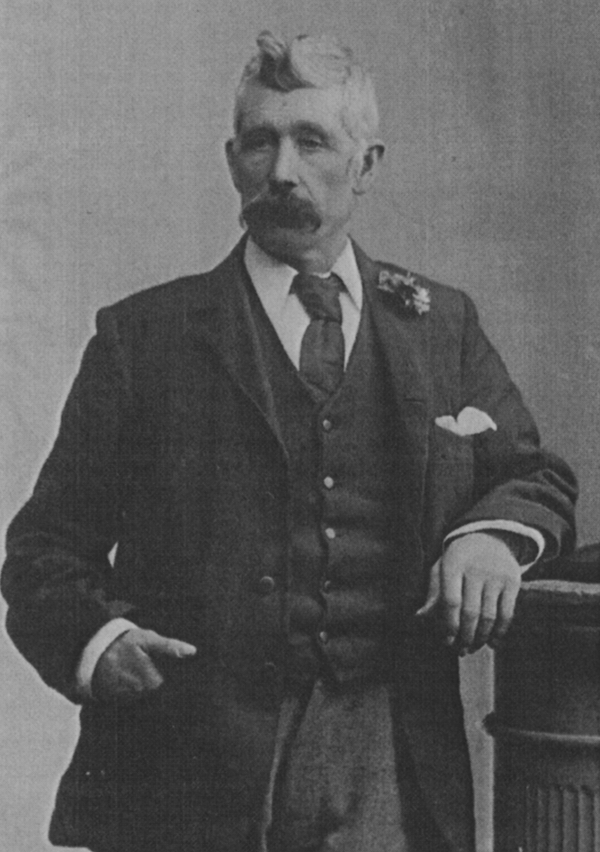

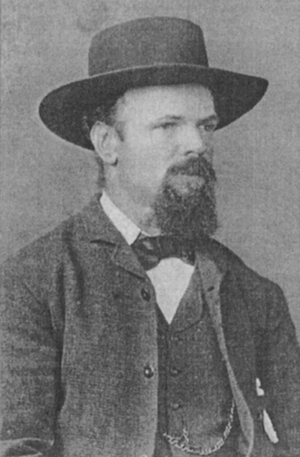

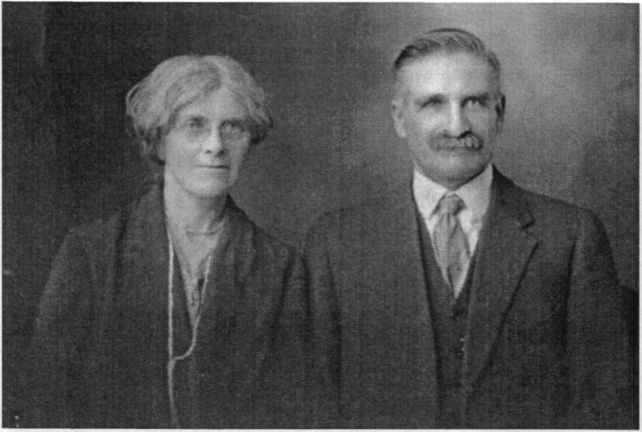

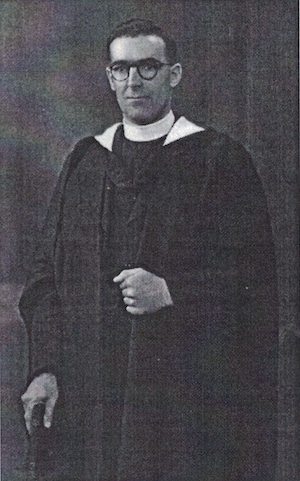

Michael Grace McCue >

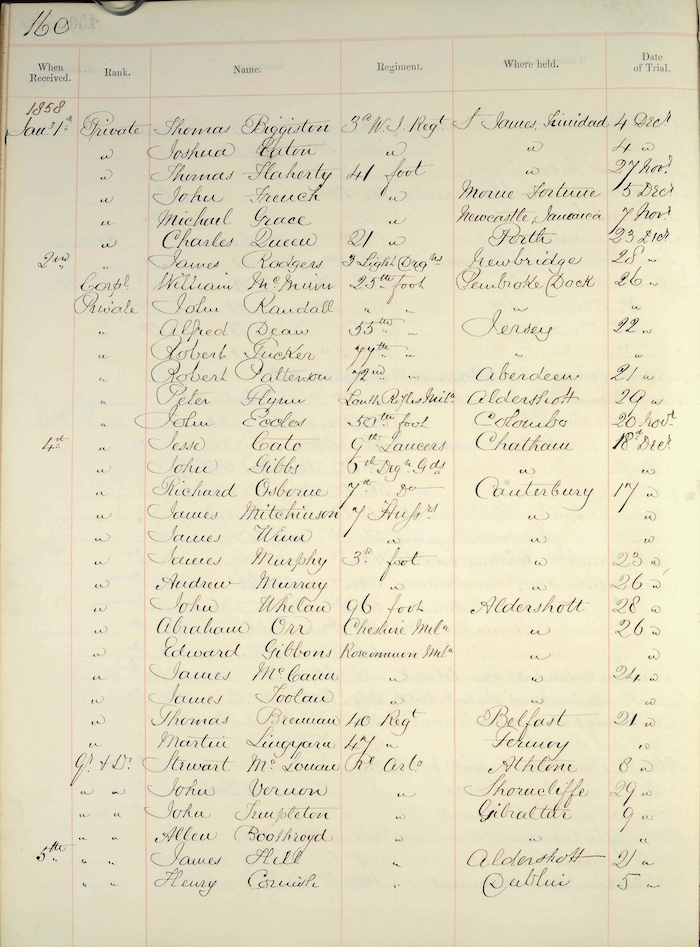

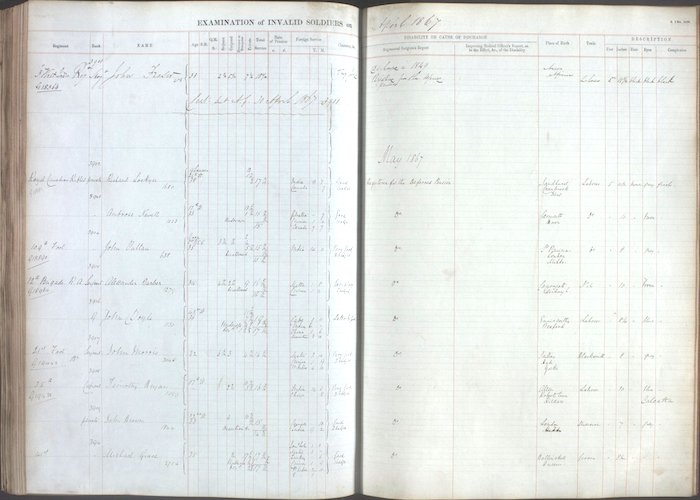

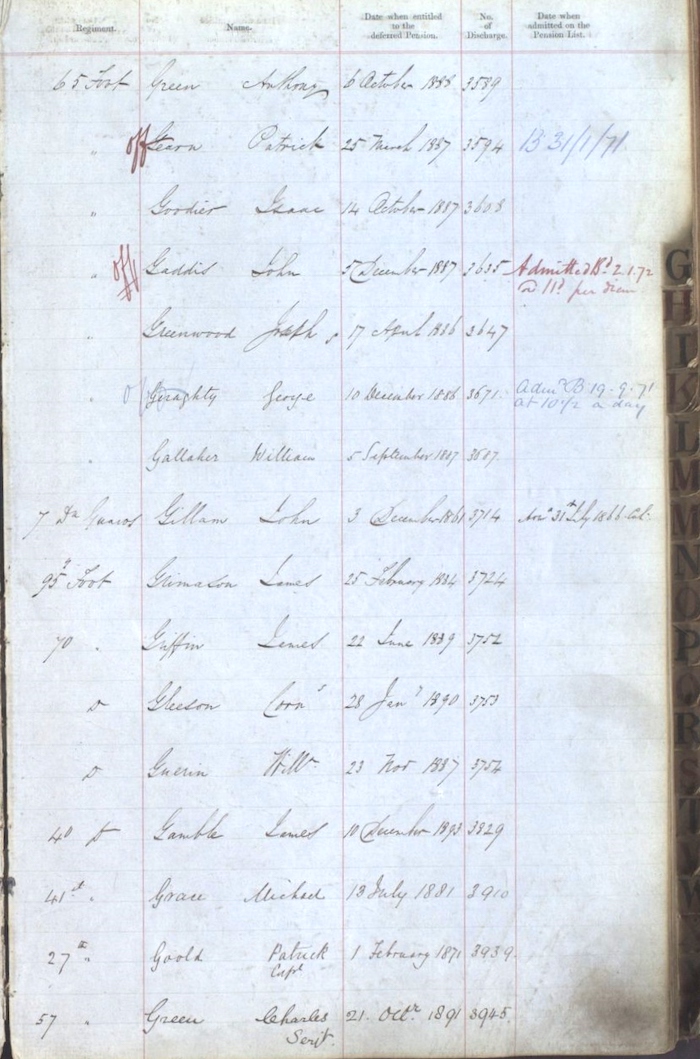

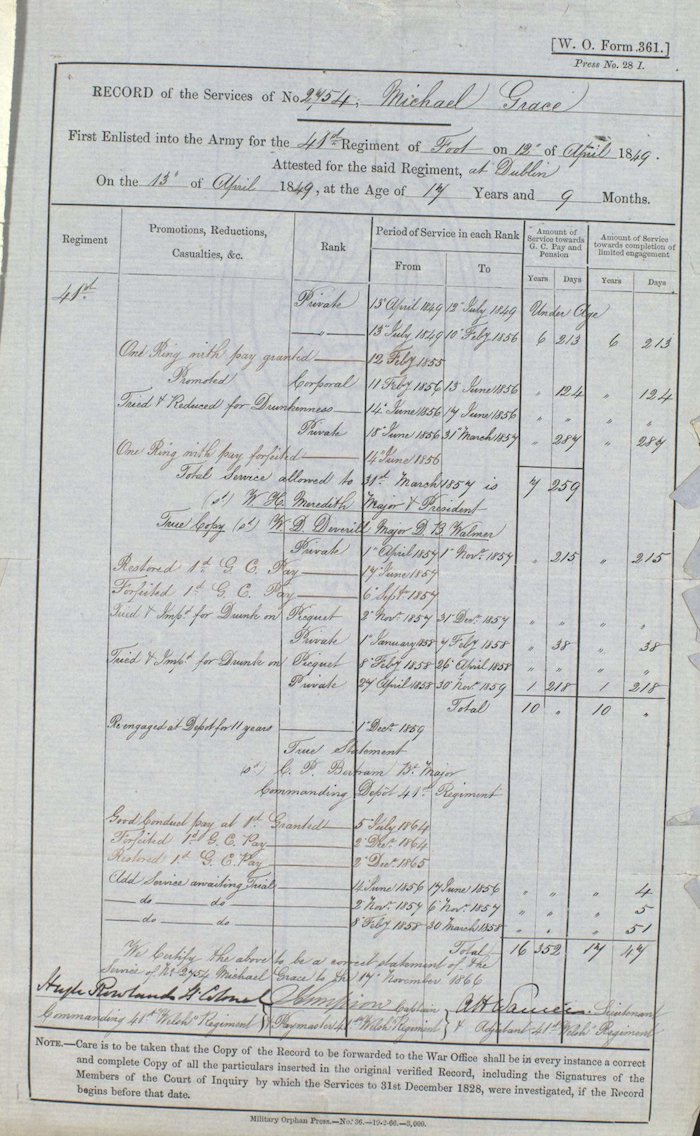

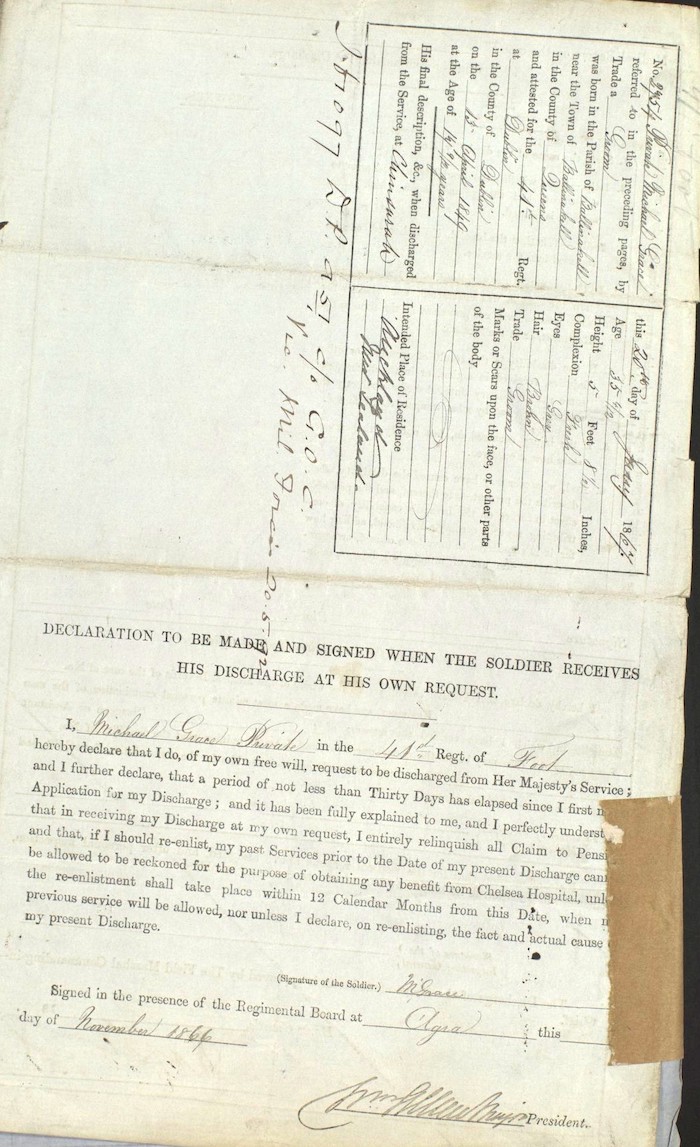

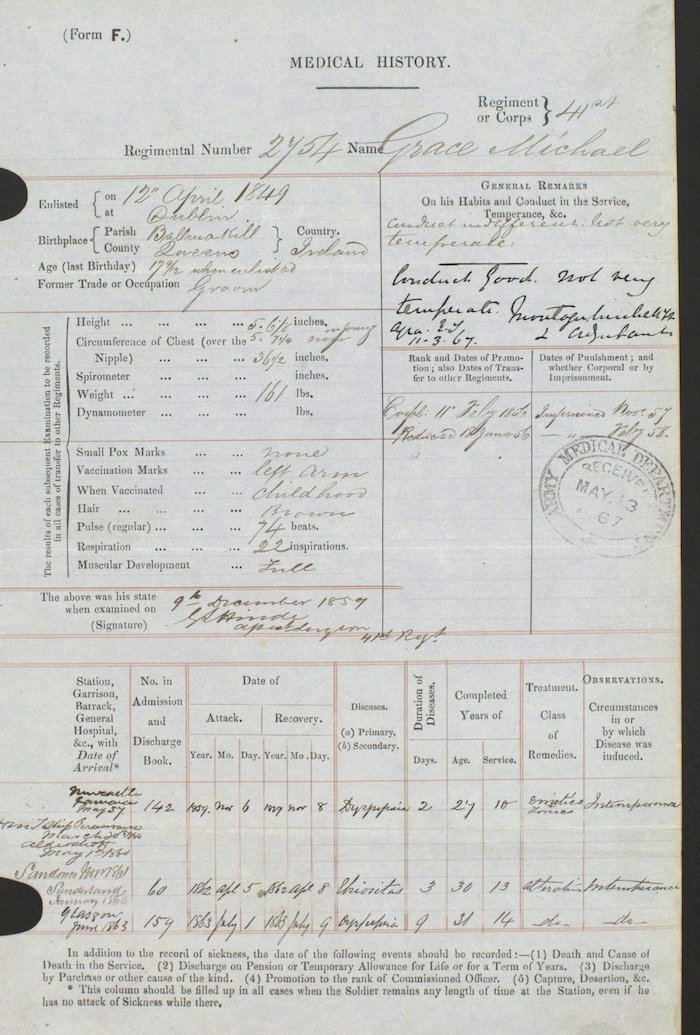

When Mick was thirteen he went to sea as a cabin boy. He was in Waterford on 12 April 1849 when he enlisted in the British Army - 41st Welsh Regiment of Foot, whose headquarters at that time were in Cork, Ireland. His number was 2754 and he is described as being 5 feet 6 inches in height and aged 17 years and 9 months. Michael served in the Crimea War (1854-56) at Alma, Sevastopol and lnkerman and claimed to have seen the charge of the Light Brigade. We have the gruesome tale, handed down to his grandchildren, of him lying in wait for the enemy and chopping their heads off with a sword as they came through a narrow pass.

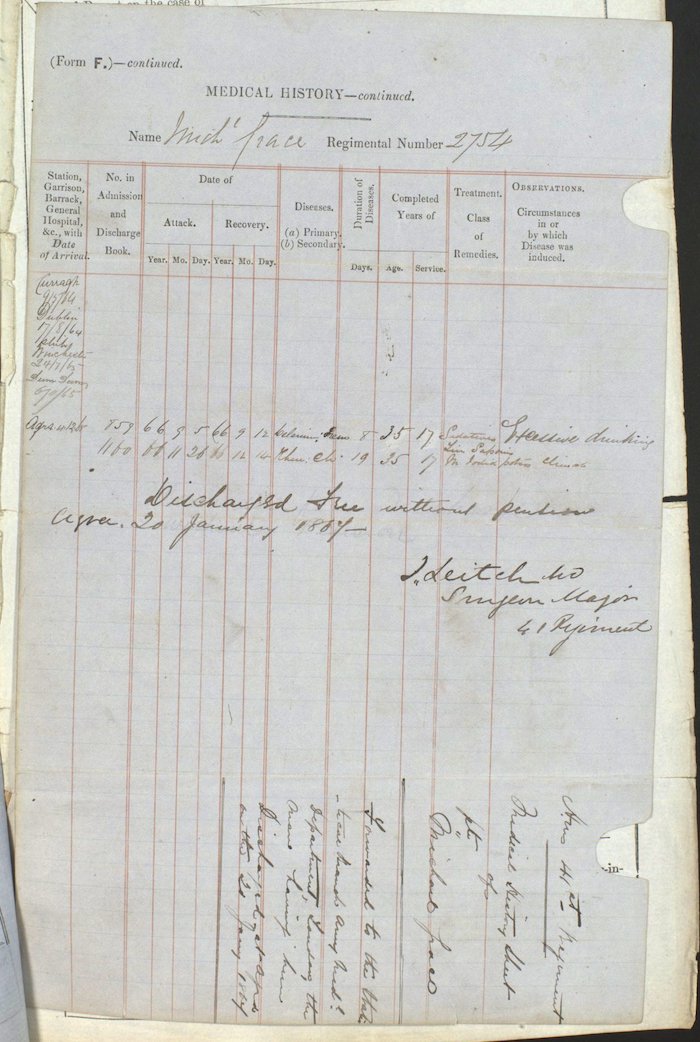

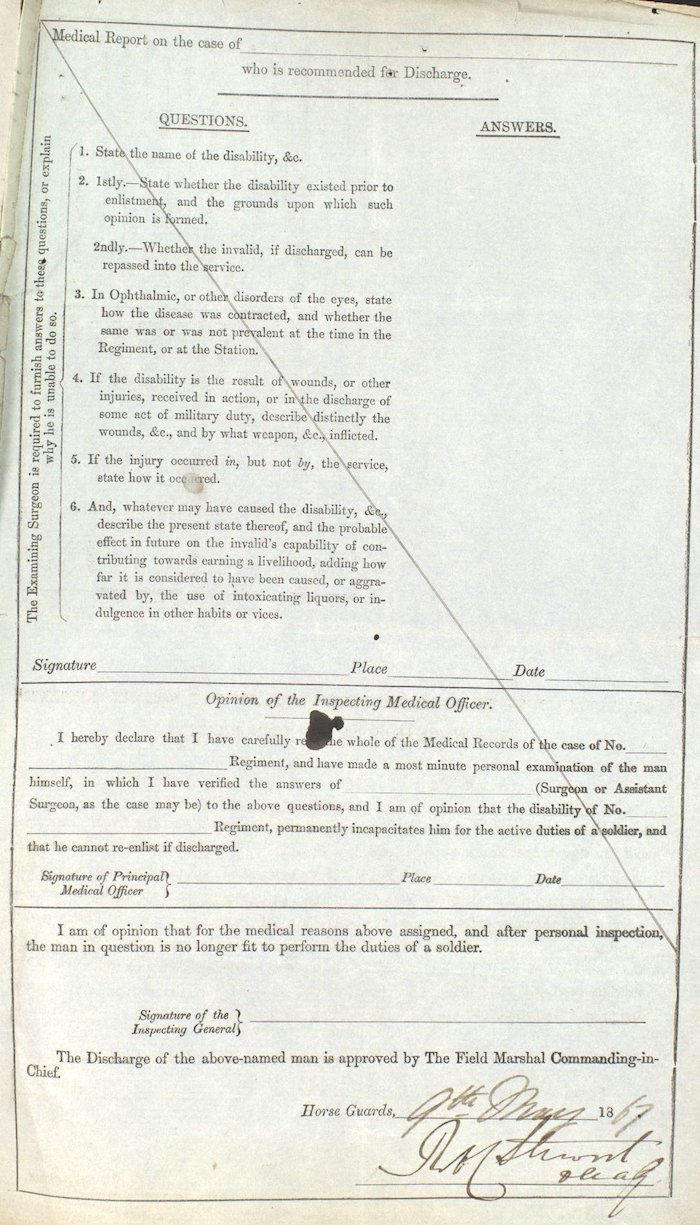

Michael was in lndia at the time of the mutiny in 1857. Other recorded postings included Cephalonia in Greece, 1851, Newcastle, 1861, and Sunderhead, June 1862. He carried the scars of two bullet wounds, one in his arm, the other where a bullet went through his nose and lodged in the roof of his mouth. He was granted a small pension - six pence for each wound, but the frequency of this rate is unknown. Both Marjorie and Jeff tell me there was a silver medal acknowledging the various campaigns Mick served in, but what has happened to this, no one seems to know.

Mick ended his army career in India and was discharged at Agra on 20 January 1867 - good conduct, 1 penny a day - having reached the rank of Quarter-Master Sergeant with his own batman to attend to him. From lndia, Mick migrated to Australia, arriving at Geelong, Victoria from Calcutta aboard the ‘Eldorado‘, on 30 March 1867. He is listed as British Army, aged 35 years. He was known at that time as Michael GRACE.

Marjorie Mathieson writes:

“He told my Dad [Mick's son, the Rev Jack McCue] he wrote to his ‘father and got permission to use [the] McCue name. We think his mother married John McCue (widower) the grandfather of the family. We were told a priest arranged a Michael Grace McCue marriage. Hearsay [claims] his biological

page 34

Cottage in Ireland

Where Michael McCue lived as a child.